THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF

A HUNTED PRIEST

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY

OF A HUNTED PRIEST

JOHN GERARD, S.J.

Translated from the Latin by

Philip Caraman, S.J .

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Original United States edition:

1952 by Pellegrini & Cudahy, New York

This edition published by permission of the

Society of Jesus, British Province, London

1988 by Philip Caraman

All rights reserved

Cover art:

Edward Oldcorne and Nicholas Owen by Gaspar Bouttats

line engraving, mid-17th century

National Portrait Gallery, London

Cover design by John Herreid

Published 2012 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

Introduction by James V. Schall 2012 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-450-7

Library of Congress Control Number 2011940705

Printed in the United States of America

FOR M. C. DARCY

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

In my early years in the Society of Jesus, I recall that this book, The Autobiography of a Hunted Priest , was read at table from the 1950 edition of Father Caraman. At the time, it struck me as an ecclesiastical adventure story with a rather happy endingthat is, John Gerard, its author, finally managed in 1606 to escape from England to Belgium without being, like so many of his Jesuit friends, hung, drawn, and quartered. This was that most brutal way the English Protestant establishment chose to enforce its will. Gerard died a normal death in the English College in Rome in 1637. On first listening to it, I was struck by the thought that this book describes a persecution of Catholics that could not happen here. One is no longer quite so sure. It may, in fact, be a very up-to-date book in its own way.

On October 5, 1597, Gerard is famous for having managed to escape from the maximum-security Tower of London prison by lowering himself down its walls with a rope. He eluded capture often enough, though not always. He was tortured brutally. In the England of this period the last quarter of the 1500s, it was against the law to be a priest. The English Jesuits with members of other Orders and diocesan clergy who remained faithful to the Catholic tradition often found refuge with various Catholic families. Indeed, the most moving sections of this account often are those of faithful men and women who tried to protect and hide priests. Many of these good folks quite literally laid down their lives for their priest-friends and the truths they stood for.

The effort to provide hiding holes in large mansions and houses where priests could be invisible to persuivants is famous. The ingenious way that these hiding places were constructed so that even the most diligent agents of the police could not find them is part of the drama of this book. When priests were found hiding, often the reason for finding them was not because of faulty construction but because someone betrayed them to the authorities. The Judas theme is also in this book. The subtleties of persecution were such that Catholic families whose houses were investigated had to pay the agents of their enemies for the searching of their own homes.

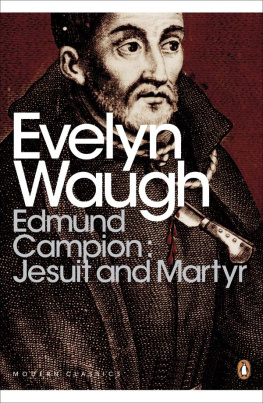

The Autobiography does not spare any sensitivity about the utter brutality of the English Protestants determined to stamp out the traditional faith of the English people. Yet, the acceptance of martyrdom often does reveal a certain almost lightsomeness in serving the Lord in this way. The seminaries on the European continent, where young Englishmen were educated to return home, were filled with men who were under no illusions. They knew what was in store for them if they were captured on their return to their homeland. They knew many were taken by authorities. The list of English martyrs from this period is long and distinguishedSouthwell, Campion, Olgive, Fisher, to name but a few.

This noble record, of course, must be understood in the light of the fact that Catholicism was largely eliminated in these and following decades. All the bishops but one went over to the Church of England. The legal penalties against Catholics lasted into the nineteenth century and in some minor form still exist. The visit of Pope Benedict XVI to England in 2010 was a poignant reminder of how difficult reconciliation, forgiveness, acceptance, and truth come together even after so many centuries. The Church of England is but a shadow of its former self.

Still these young priests in Europe did return. They understood that they were to do what they could to serve the Catholics and to convert back those who had lapsed. One cannot but be surprised at the amount of spiritual direction, retreats, and instructions that Gerard gave to all sorts of people in these constrained circumstances. Life under persecution did not interfere with the spiritual life of those persecuted, but in many ways enhanced it.

In the tradition of Thomas More, we also have here a clear carrying out of the Catholic teaching about politics and faith under persecution. The Jesuits were under orders not to involve themselves in politics. They were there to serve God and provide the sacraments. They made this distinction between faith and politics that was not, of course, shared by the Protestants. The Protestant establishment did follow the letter of the common law. If someone was to be tortured, a writ of authority was needed. If evidence could not be provided, the detained were released. Many of the most dramatic passages in Gerards account have to do with torture, law, and evidence against men and women who would not betray their friends or their faith.

Another striking aspect of this book is how clearly those English Jesuits and other priests drew the line between what was permissible for them and what was not. The famous issue of equivocation comes up herethat is, does one have to tell the literal truth when one is being unjustly questioned. If an ambiguous answer can follow from the question, it is not the fault of the one being persecuted if the authorities misunderstand the answers that the state has no right to ask.

Gerard was finally ordered by his religious superiors to write his memoirs. This is what we read here. Belloc once said that the only way we could save such graphic experiences so that they do not slip away altogether is to write of them. Without this rather charming account of Gerards experiences during the English persecution of the Catholic Church we would not be able to imagine so well its nature and scope. His Jesuit superiors were prescient in obliging him to tell us what he saw.

We have here the classic case of a government changing the religion of its heritage and people. To do this, it passes laws and sanctions designed to stamp this traditional religion out. The lesson of the English reformation is not that it cannot be done. Its lesson is that it can be in this culture or that. For those who think that governments can do no wrong, this account makes sober reading, unless of course we hold that this religion should be stamped out.

Gerard implies that the one thing the Lord requires of us, even in persecution, is persistence in virtue and faithfulness of belief and sacrament. For this cause, many good priests and laymen gave their lives. They were officially traitors to their country even though they stood for what the country traditionally stood for. In fact, they were closer to Socrates and Christ. They gave their lives so that others could believe and live. We are still in their debt. Ultimate sacrifices of life and limb in the name of truth do not always win in this world. None of the men depicted here, including John Gerard himself, ever thought that it would.

Father James V. Schall

Georgetown University

Feast of the Archangels

September 29, 2011

TRANSLATORS PREFACE

In his own preface, John Gerard says that he wrote this account of his eighteen years in England at the order of his Superiors. This order was probably given in the spring of 1609, four years after the execution of Henry Garnet, the last event mentioned in the text. At that time Gerard, who had now recovered from the physical and mental strain of his last months in England, was living in Louvain, where he was helping to train the English novices of the Society of Jesus for the mission he had just left. We do not know the origin of the order, but it is probable that in his conversation with his novices Gerard frequently told anecdotes of hunted priests, of torture, and the everyday heroism of his friends among the English laity; and that one of his hearers had the happy idea of suggesting to the General of the Jesuits that he should write an account of his missionary life in England.

Next page