PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN CLASSICS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Gauteng 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published in Great Britain by Longman 1935

Published by Penguin Books 1953

Published in Penguin Classics 2011

This edition published in Penguin Classics 2012

Copyright 1935, 1947 by Evelyn Waugh

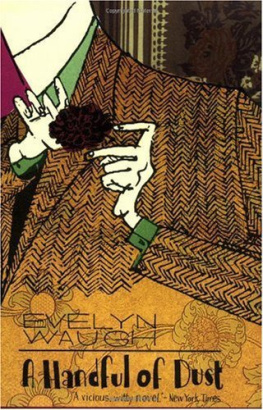

Cover photograph The Bridgeman Art Library

All rights reserved

The text of this book, with some emendations, follows an edition of 1961, which was the last overseen by the author

ISBN: 978-0-24-196204-6

PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

EDMUND CAMPION

Evelyn Waugh was born in Hampstead in 1903, the second son of publisher Arthur Waugh. He was educated at Lancing and at Hertford College, Oxford, where he read Modern History. Waugh taught at preparatory schools in North Wales and Buckinghamshire for a short time, which provided the inspiration for his first novel, Decline and Fall, published in 1928. In 1930 Waugh was received into the Catholic Church. He became one of the most fted literary celebrities of his day with the publication of his satirical novels Vile Bodies (1930), Black Mischief (1932), A Handful of Dust (1934) and Scoop (1938). During these years he also travelled widely, visiting the Mediterranean countries, the Middle East, Africa and South America, and publishing the celebrated travel books Labels (1930), Remote People (1931), Ninety-Two Days (1934) and Waugh in Abyssinia (1936). In 1939 he was commissioned in the Royal Marines and later transferred to the Royal Horse Guards, serving in the Middle East and in Yugoslavia. In 1942 he published Put Out More Flags and then, in 1945, Brideshead Revisited, which became an international bestseller. Men at Arms, the first volume of a trilogy about the Second World War, came out in 1952 and won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize. The other volumes, Officers and Gentlemen and Unconditional Surrender, followed in 1955 and 1961. The semi-autobiographical novel The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold appeared in 1957 and A Little Learning, the first volume of his unfinished autobiography, in 1964. For many years Waugh lived with his second wife and six children in the English countryside. He died in 1966, acknowledged as one of the greatest novelists of his generation, and also renowned for the brilliance of his journalism, essays, diaries and correspondence, much of which was published to great acclaim after his death.

Waugh said of his work: I regard writing not as investigation of character but as an exercise in the use of language, and with this I am obsessed. I have no technical psychological interest. It is drama, speech and events that interest me. Waughs obituary in Time magazine stated that Waugh had developed a wickedly hilarious yet fundamentally religious assault on a century that, in his opinion, had ripped up the nourishing taproot of tradition and let wither all the dear things of the world. The New York Review of Books called him King of the novelists and Clive James hailed him as the supreme writer of English prose in the twentieth century in direct line with Shakespeare and Dickens.

To

M. C. DArcy, S. J.

Sometimes Master of Campion Hall

Oxford

Preface

In 1934, when Campion Hall, Oxford, was being rebuilt on a site and in a manner more worthy of its distinction than its old home in St Giless, I wished to do something to mark my joy in the occasion and my gratitude to the then Master, to whom, under God, I owe my faith. A life of the Blessed Edmund Campion seemed the most suitable memorial. The alternatives were either a drastic revision of Richard Simpsons excellent work, which had long been out of print and had been corrected in many particulars by subsequent research, or to attempt an entirely new book. I chose the latter but Simpsons strong foundations support my structure and it is to him that I owe the greatest debt. I received invaluable help from Father Basset and Father Booth, from the late Father Watts of Stonyhurst, Father Hicks of Farm Street and Mr Douglas Woodruff. I was privileged to use the copious collection of notes and documents collected by one of the Fathers at Farm Street for what would have been, had he lived, the definitive biography.

There is great need for a complete, scholars work on the subject. This is not it. All I have done is select the incidents which struck a novelist as important and relate them in a single narrative.

It shall be read as a simple, perfectly true story of heroism and holiness.

We have come much nearer to Campion since Simpsons day. He wrote in the flood-tide of toleration when Elizabeths persecution seemed as remote as Diocletians. We know now that his age was a brief truce in an unending war. The Martyrdom of Father Pro in Mexico re-enacted Campions in faithful detail. We are nearer Campion than when I wrote of him. We have seen the Church drawn underground in country after country. In fragments and whispers we get news of other saints in the prison camps of Eastern and South-eastern Europe, of cruelty and degradation more savage than anything in Tudor England, of the same, pure light shining in darkness, uncomprehended. The hunted, trapped, murdered priest is our contemporary and Campions voice sounds to us across the centuries as though he were walking at our elbow.

EVELYN WAUGH

PART ONE

The Scholar

One

The Scholar

In the middle of March 1603 it was clear to everyone that Queen Elizabeth was dying; her doctors were unable to diagnose the illness; she had little fever, but was constantly thirsty, restless and morose; she refused to take medicine, refused to eat, refused to go to bed. She sat on the floor, propped up with cushions, sleepless and silent, her eyes constantly open, fixed on the ground, oblivious to the coming and going of her councillors and attendants. She had done nothing to recognize her successor; she had made no provision for the disposal of her personal property, of the vast, heterogeneous accumulation of a lifetime, in which presents had come to her daily from all parts of the world; closets and cupboards stacked high with jewellery, coin, bric--brac; the wardrobe of two thousand outmoded dresses. There was always company in the little withdrawing room waiting for her to speak, but she sighed and sipped and kept her silence. She had round her neck a piece of gold the size of an angel, engraved with characters; it had been left to her lately by a wise woman who had died in Wales at the age of a hundred and twenty. Sir John Stanhope had assured her that as long as she wore this talisman she could not die. There was no need yet for doctors or lawyers or statesmen or clergy.