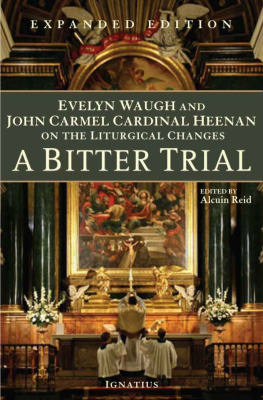

A BITTER TRIAL

A Bitter Trial

Evelyn Waugh

and

John Carmel Cardinal Heenan

on the

Liturgical Changes

Expanded Edition

Edited by

Alcuin Reid

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

First published in 1996 by Saint Austin Press, England

1996 & 2000 by Alcuin Reid

Cover photograph by S. Smith Photogaphy, Chicago

(An anticipatory Mass in the older form of the Roman rite

for the Feast of the Exultation of Holy Cross at

Iglesia de San Gins de Arls

in Madrid on September 13, 2010.)

Cover design by Riz Boncan Marsella

2011 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-522-1 (PB)

ISBN 978-1-68149-004-5 (EB)

Library of Congress Control Number 2011905245

Printed in the United States of America

Dedicated

to the memory of

Francis Aloysius Doolan

19241986

Priest, mentor, and friend

Maybe he had doubts about the orders,

but [he] never had a doubt about obeying them .

Archbishop T. F. Little

Contents

(23 November 1962)

(25 November 1962)

(15 March 1963)

(16 March 1963)

(2 February 1964)

(6 August 1964)

(7 August 1964)

(16 August 1964)

(20 August 1964)

(25 August 1964)

(28 August 1964)

(14 September 1964)

(All Saints 1964)

(7 February 1965)

(3 January 1965)

(17 January 1965)

(27 February 1965)

(15 April 1965)

(24 April 1965)

(31 July 1965)

(4 August 1965)

(21 August 1965)

(8 September 1965)

(12 January 1966)

(14 January 1966)

(9 March 1966)

(30 March 1966)

(14 April 1966)

(21 April 1966)

(24 October 1967)

(21 November 1967)

(15 September 1969)

(29 October 1971)

Foreword

Joseph Pearce

Much water has flown under Tibers bridges, wrote Alec Guinness in his autobiography, carrying away splendor and mystery from Rome, since the Pontificate of Pius XII. Writing in the mid-eighties, Guinness lamented the banality and vulgarity of the translations which have ousted the sonorous Latin and little Greek from the liturgy and regretted that [h]and-shaking and embarrassed smiles or smirks have replaced the older courtesies. Although dismayed by the nature of the liturgical changes, Guinness was sure that the Church would recover from such nonsense, so long as the God who is worshipped is the God of all ages, past and to come, and not the Idol of Modernity, so venerated by some of our bishops, priests and mini-skirted nuns.

Even as Guinness was lamenting the chaos that followed in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, there were signs that the Church was recovering from the modernist encroachments that had sought to marry her to what Waugh, in his article in the Spectator that opens the present volume, had rightly called our own deplorable epoch.

A spirit of restoration had been heralded in 1978 by the election of John Paul II to the papacy. Schooled in modern philosophy, yet a man of deep love for the ancient faith, Pope John Paul II attempted to implement a more faithful interpretation of the Second Vatican Council, which called for a renewal, rather than a deconstruction, of the liturgy. Thereafter the beauty and authority of Tradition, presumed dead after Vatican II, began to show signs of resurrection.

Perhaps, with the wisdom of hindsight, we can now see the election of John Paul II as the date at which the high tide of the modernist encroachment within the Church began to turn. Yet there was always the danger that John Pauls successor would lack the courage or the ability to continue with the reform of the reform. Would the next pope exercise his power to exorcise the darkness? With this question looming ominously over the Church, it is no wonder that faithful Catholics around the world leapt for joy when they heard the news that Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger had been elected pope. Their exhilaration, and their exhalation of a deep sigh of relief, at Pope Benedicts accession to the Throne of Peter helped to soften the sorrow at the passing of his illustrious predecessor. Mixed with the grief was the joyful confidence that the Church and her sacred liturgy were in safe hands.

Yet, in the light of this resurrection of liturgical Tradition within the Church, it is important that we remember the darkness from which the Church is now emerging, and the suffering it caused to many faithful Catholics who found themselves seemingly deserted in the gloom. As Alcuin Reid reminds us in his introduction to this volume, the bitter trial that tested the faith of Evelyn Waugh and so many of his generation, as well as the almost-impossible situation in which Cardinal Heenan and many other clergy found themselves, must not be forgotten. And, lest we forget, lets remind ourselves of the background to Waughs conversion to Catholicism and the reason that he remained faithful to the Church and her Tradition.

On 21 August 1930 Waugh had written to the Jesuit Martin DArcy that he had come to the realization that the Catholic Church was the only genuine form of Christianity [and] that Christianity is the essential and formative constituent of western culture. Six weeks later, on 29 September, Father DArcy received Waugh into the Church. In the wake of his conversion and the controversy it caused, Waugh wrote an article for the Daily Express explaining his reasons for becoming a Catholic:

It seems to me that in the present phase of European history the essential issue is no longer between Catholicism, on one side, and Protestantism, on the other, but between Christianity and Chaos....

Today we can see it on all sides as the active negation of all that western culture has stood for. Civilizationand by this I do not mean talking cinemas and tinned food, nor even surgery and hygienic houses, but the whole moral and artistic organization of Europehas not in itself the power of survival. It came into being through Christianity, and without it has no significance or power to command allegiance. The loss of faith in Christianity and the consequential lack of confidence in moral and social standards have become embodied in the ideal of a materialistic, mechanized state.... It is no longer possible... to accept the benefits of civilization and at the same time deny the supernatural basis upon which it rests.

Asserting that Christianity is essential to civilization and that it is in greater need of combative strength than it has been for centuries, Waugh argued that Christianity exists in its most complete and final form in the Roman Catholic Church. On 8 October 1930 the Bystander observed of Waughs conversion that the brilliant young author [was] the latest man of letters to be received into the Catholic Church. Other well-known literary people who have gone over to Rome include Sheila Kaye-Smith, Compton MacKenzie, Alfred Noyes, Father Ronald Knox and G. K. Chesterton. The list was far from exhaustive. By the 1930s the rising tide of converts to Catholicism had become a torrent. Throughout that decade there were some twelve thousand converts a year in England alone.

The burgeoning Catholic revival was also flourishing in the United States. A few weeks after Waughs reception into the Church, G. K. Chesterton was in New York debating with the famous Chicago lawyer Clarence Darrow. The debate was entitled Will the World Return to Religion? An audience of four thousand heard both sides of the debate and then voted on the question. The result was 2,359 for Chestertons point of view and 1,022 for Darrows. Meanwhile, in Europe, there was a wave of literary converts to rival that in England. These included Franois Mauriac, Lon Bloy, Jacques Maritain, Charles Pguy, Henri Ghon, Giovanni Papini, Gertrud von le Fort, and Sigrid Undset, all of whom were either converts or else reverts who had lost their faith but had returned to the Church.

Next page