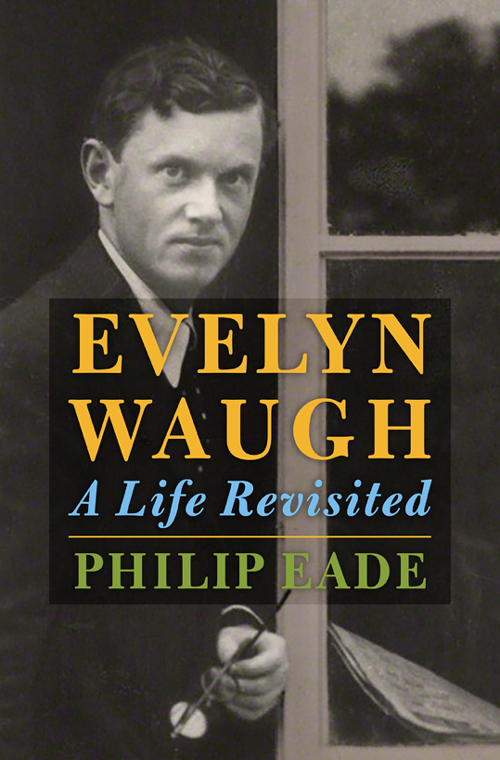

EVELYN

WAUGH

A Life Revisited

PHILIP EADE

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY NEW YORK

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Rita

All photographs are courtesy of Alexander Waugh unless otherwise stated. While every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders, the publishers would be pleased to rectify at the earliest opportunity any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

FIRST PLATE SECTION

SECOND PLATE SECTION

THIRD PLATE SECTION

In one of the funniest scenes in Evelyn Waughs novel Brideshead Revisited, Charles Ryders father pretends to suppose that his sons very English friend, Jorkins, is an American.

Good evening, good evening. So nice of you to come all this way.

Oh it wasnt far, said Jorkins, who lived in Sussex Square.

Science annihilates distance, said my father disconcertingly. You are over here on business?

Mr Ryder never makes his misapprehension explicit enough to give Jorkins the opportunity of correcting him but he is careful to explain any peculiarly English terms that come up in conversation, translating pounds into dollars, as Waugh writes, and courteously deferring to him with such phrases as Of course, by your standards ; All this must seem very parochial to Mr Jorkins; In the vast spaces to which you are accustomed

Evelyn Waugh played similar games in real life. When a young American fan named Paul Moor wrote to him out of the blue in 1949, he was amazed to be invited by return to stay at Waughs home in Gloucestershire. Moor later described to Martin Stannard his reception by Waughs butler and, almost immediately, being confronted by his idol, who was wearing a dinner jacket and greeted him with a show of astonishment: But I thought youd be black! What a disappointment! My wife and I had both counted on dining out for months to come on our story of the great, hulking American coon who came to spend the weekend. Dazed by his hosts exaggerated absence of taste, Moor never realised that Waugh was making a joke about his surname.

Later at dinner, when the butler went to fill Moors wine glass, Waugh waved towards a jug on the sideboard, declaring, Im sure youd prefer iced water, as though that was all Americans liked to drink. When Moor bravely declined, Waugh exclaimed, But weve gone to so much trouble! Soon he was off again: At breakfast tomorrow I expect youll want Popsy Toasties or something like that, wont you? The teasing went on throughout Moors three-day visit and yet the baffled innocent came away with the impression that his host was an essentially kind man.

A brilliant and extraordinarily clear writer, Evelyn Waugh could hardly have been easier to understand and enjoy on the page; yet the peculiar traits of his character were often harder to fathom, inclined as he was to fantasy, comic elaboration and mischievous disguise. If the imaginative flourishes in his letters were intended to entertain the recipients, the eccentric and sometimes frightening faades he adopted in person were more often designed as defences against the boredom and despair of everyday life.

Moor was right about Waughs kindness and one only has to read his novels to find the deep humanity behind the forbidding front. One of his more sympathetic American obituarists accurately described him as a man of charity, personal generosity and above all understanding, however it is also true that he rarely went out of his way to advertise the benevolent side of his nature. I know you have a great heart, his close friend Diana Cooper wrote to him, but you hate to put it on your sleeve rightly up to a point but rather than sometimes letting it fly there, by its own dear volition, you pin a grinning stinking mask on the site.

* * *

This is not a critical biography in the sense that it does not seek to reassess Evelyn Waughs achievements as a writer, but aims to paint a fresh portrait of the man by revisiting key episodes throughout his life and focusing on his most meaningful relationships. Drawing on a wide variety of sources published and unpublished it also seeks to re-examine and rebalance some of the distortions and misconceptions that have come to surround this famously complex and much mythologised character.

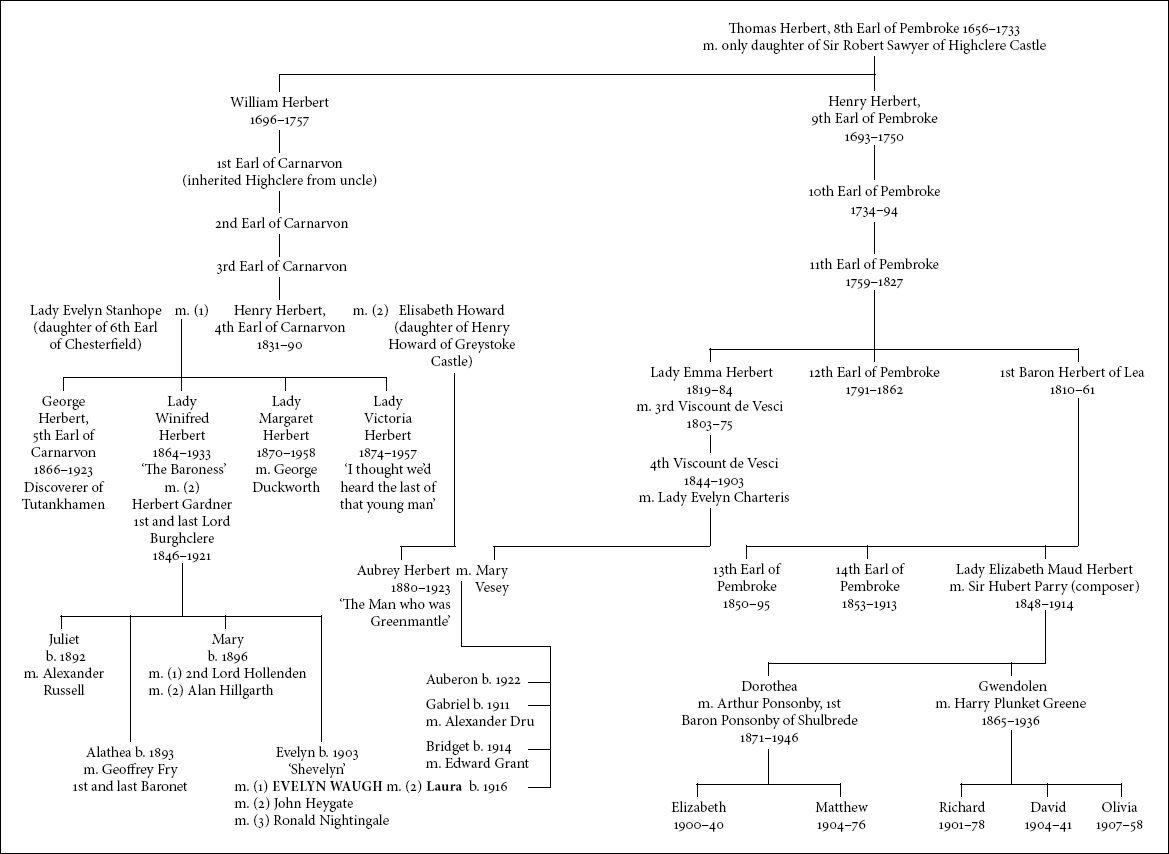

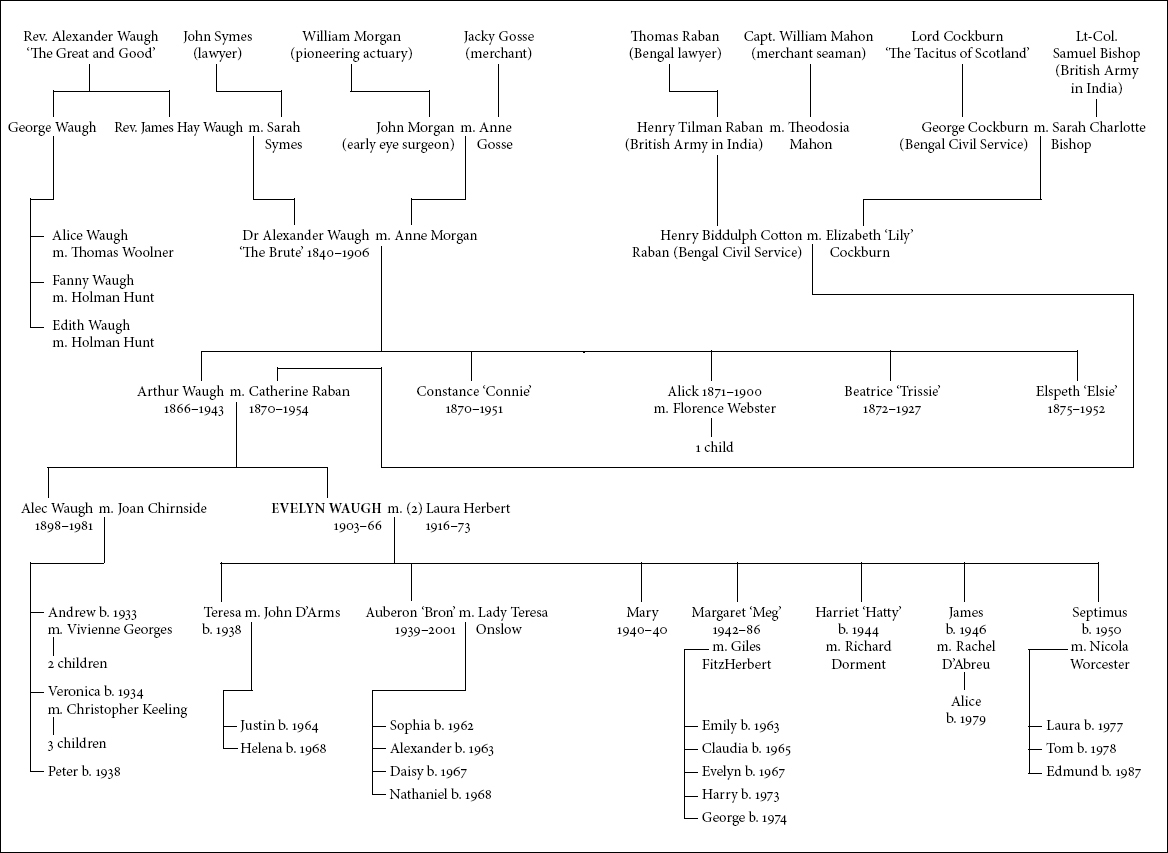

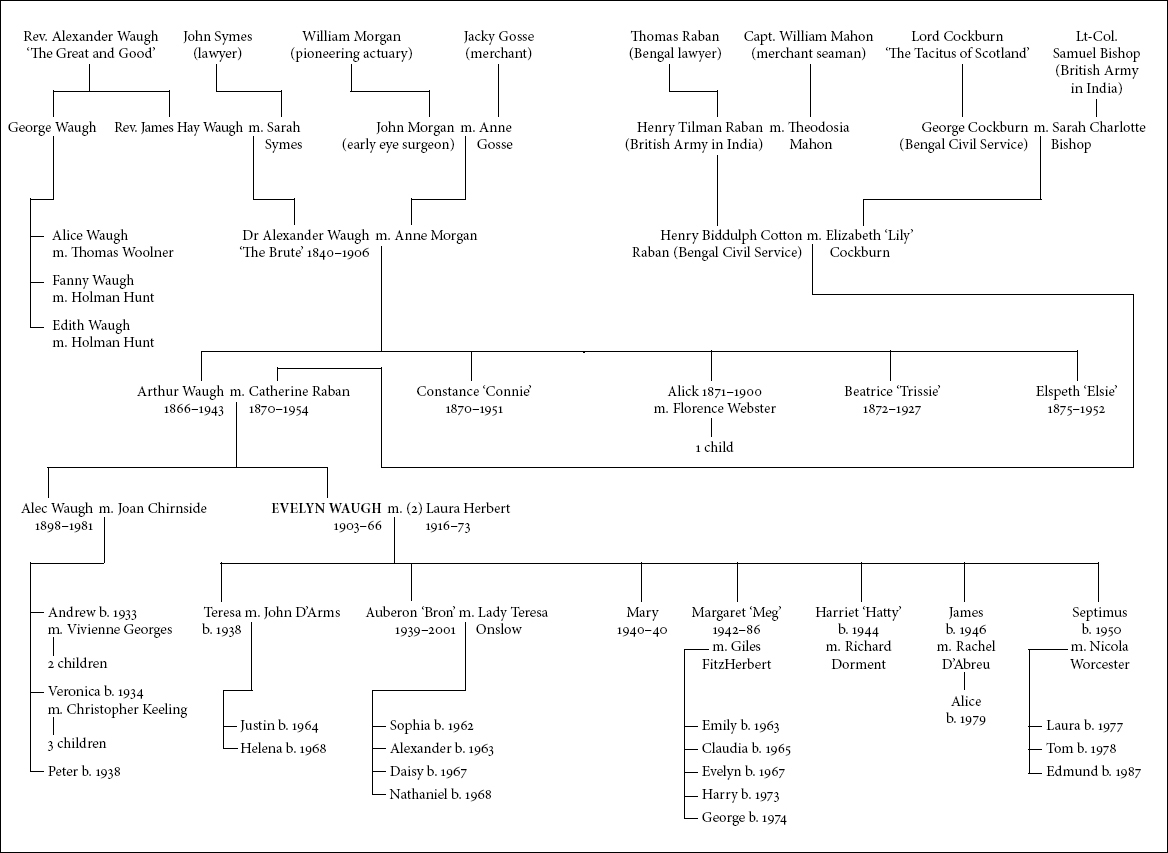

My biggest thank you is to Alexander Waugh, who suggested the idea of a new biography to mark the half-centenary of his grandfathers death and gave me unfettered access to his archive which has supplied a great deal of the unpublished material in the book. In the course of researching his own richly entertaining Fathers and Sons: The Autobiography of a Family (2005) and more recently as editor-in-chief of the first Complete Works of Evelyn Waugh (Oxford University Press; the first of forty-three volumes is due in 2017), he has assembled the most comprehensive Waugh study archive in the world, comprising original manuscripts, rare transcripts, photographs, rare editions, memorabilia, professional records and copies of the vast majority of the existing primary and secondary material.

Among the numerous unpublished letters that cast fresh light on Evelyn Waughs life there are more than eighty written to Teresa Baby Jungman, with whom he fell hopelessly in love in the 1930s, and who he later claimed formed the basis for every character male and female in his masterpiece A Handful of Dust. These letters have long been regarded as the holy grail of Waugh biography and while charting the course of this unrequited affair they show a deeply romantic and tender side to his character that counters the popularly-held view of his heartlessness.

No less significant is the brief unpublished memoir written by Evelyn Waughs first wife, Evelyn Gardner, describing the short-lived marriage that is thought to have unleashed a bitter and capricious side to his character and propelled him towards the Roman Catholic Church.

Evelyn Nightingale, as she became by her third marriage, has had a harsh press and was understandably wary of Waughs biographers, declining most requests for interviews. She was however forthcoming with Michael Davie, editor of The Diaries of Evelyn Waugh (1976), who interviewed her and corresponded with her regularly. In her 1994 obituary in The Independent he described her as a much more substantial person as well as a much nicer one than the propaganda spread by Waughs circle had led me to expect. After his own death in 2005, Davies extensive collection of Evelyn Waugh papers (including his interview transcripts and copious correspondence with Evelyn Nightingale) were acquired by Alexander Waugh. These records constitute another significant cache of untapped primary sources in his archive.

In the course of editing Evelyn Waughs diaries Davie had undertaken intensive background research, interviewing several key figures in Waughs circle besides his first wife, in several cases shortly before they died. Some of them Davie had sought out; others contacted him to correct false impressions or, as they believed, the outrageous fictions in the diaries as they first appeared in