Praise for Fathers and Sons

A wonderful critical-loving job a stupendous story.

V. S. Naipaul

Very funny as good as a great novel in its depiction of the human condition as embodied in the relationship between father and son.

Katherine A. Powers, Boston Globe

All fathers and sons should read it.

Humphrey Carpenter, Sunday Times

William Boyd, Guardian

Written with wit, great shrewdness, and without a trace of sentimentality.

An absorbing study of how writers process their most painfully formative experiences.

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

Michael Dirda, Washington Post Book World

Histrionic lives that are great fun to read about.

Literary skill really does seem to be hereditary Altogether an extraordinary story, admirably told, which leaves you thinking at the end what a remarkable family the Waughs are.

Geoffrey Wheatcroft, Daily Mail

One enters the house of Waugh with trepidation and leaves with regret.

Harold Evans, Wall Street Journal

A remarkable work of family history, exceptional for its honesty, inventiveness, humour, and for the beguiling individuality of its author's voice Alexander Waugh proves himself outrageously graceful and accomplished with a talent that needs no help at all from his illustrious forebearers.

Selina Hastings, Literary Review

[Evelyn Waugh's] grandson has given us another way to see his life and oeuvre, with a level of skill that everyone in the family would have appreciated.

Miami Herald

Told with humour and panache, with considerable inside knowledge and a perception that makes this remarkable chronicle a delight to read.

Spectator

Waugh relights the family's literary torch huge fun.

Tatler

For Bron

C ONTENTS

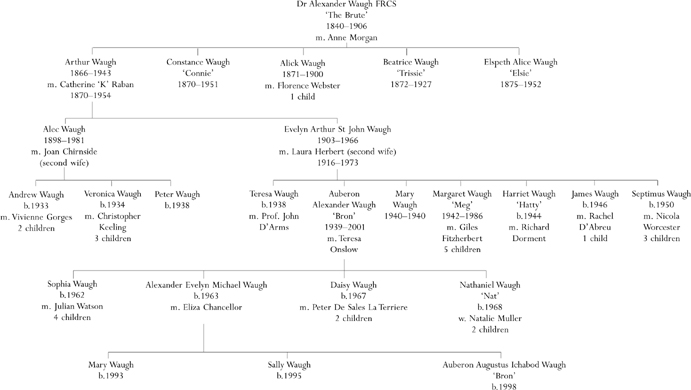

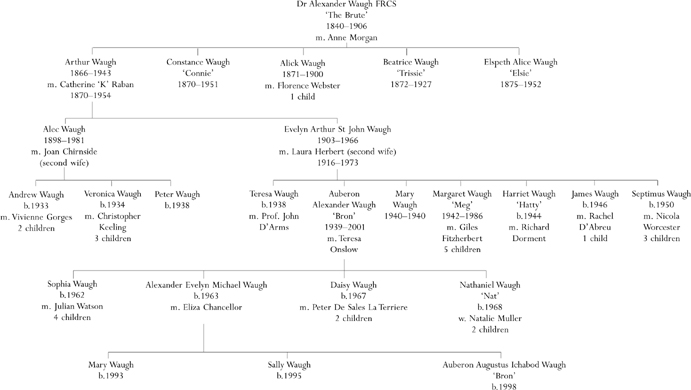

Family Tree

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

I

Pale Shadows

I shall begin with a telephone call. It was half past seven on the morning of 17 January 2001 annus horribilis when I was woken by the ringing.

He's dead, my mother said.

I'll be right over.

Quivering with excitement I told Eliza to break it to our children and to ring her father who, as planned, would act as conveyor of this dread information to the press.

Fifteen minutes later I was at Combe Florey, turning under the Elizabethan archway, looking up at my father's house. Unless I am very much mistaken, it was sulking. A gaping ambulance was parked by the perron. My elder sister was waiting for me by the front door. In the kitchen I was greeted by my mother and two sheepish paramedics. All three were ashen. Then the telephone rang already, the first shoot of my father-in-law's grapevine: reporters from the Press Association seeking verification and a quotation.

My mother answered: It is hard to sum up someone so wonderful, I heard her telling them, but I've been hanging around for forty years, so that says something.

I slunk out of the kitchen and shimmied up the stairs.

In his room the curtains were drawn, but there was just enough light to acknowledge the effect: open mouth, closed eyes; face a tobacco-stain yellow. The spectacle was disconcerting but, for the

No. That is not Papa, just a gruesome remnant. I slunk back down the stairs to the kitchen, glad, at least, that I'd seen it.

The night before was the last time we had talked together. There was a brief exchange, until he lost consciousness.

Ah, a little bird has come to see me. How delightful!

No, Papa it's me. I suppose you must have thought I was a bird because I was whistling as I came up the stairs.

It's a bit more complicated than that, he replied, with a hint of the old twinkle.

I could not be surprised that the last words he spoke to me were intended as a joke: he was always funny, but those drawn-out deathbed days were despite our finest efforts not particularly amusing. It is not true that the dying are more honest than the living I agree with Nietzsche about that: Almost everyone is tempted by the solemn bearing of the bystanders, the streams of tears, the feelings held back or let flow, into a now conscious, now unconscious comedy of vanity.

Everything is going to be dandy, Papa had insisted, as he lay uncomfortable and bemused with the skids well underneath him. Isn't life grand?

On the next day the papers were full of it: Waugh, scourge of pomposity, dies in his sleep, trumpeted The Times; End of Bron's Age was the Express's more comic effort. His death was lamented by the Australians on the front of their Sydney Morning Herald, by the Americans with long obituaries in the Philadelphia Inquirer and the New York Times (Auber on Waugh, witty mischief maker, is dead), and as far afield as Singapore, India and Kenya. At home, all of Fleet Street rallied. Even the tabloid Sun, victim of his mockery for over three decades, sounded a plucky Last Post. Here is a typical broadside from earlier days:

The Sun's motives in whipping up hatred against an imaginary elite of educated cultivated people are clear enough: Up your Arias! it shouted on Saturday in its diatribe against funding which put rich bums on opera-house seats. If ever the Sun's readers lift their snouts from their newspaper's hideous, half-naked women to glimpse the sublime through music, opera, the pictorial and plastic arts or literature, then they will never look at the Sun again. It is the Sun's function to keep its readers ignorant and smug in their own unpleasant, hypocritical, proletarian culture.

Undeterred, Britain's best-selling tabloid gallantly mourned his passing. Good Man was the heading in its leader column that day:

Auberon Waugh, who has died at the age of 61, was a writer and journalist with a unique and wonderful talent.

True he occasionally used his talent to attack the Sun. But his wit shone like a beacon. We suspect he loved us as much as we loved him.

Our sympathies are with his family. His was a great life lived well.

If this was remarkable the Daily Telegraph, a paper for which he had worked for nearly forty years, elected to treat his death as though it were the outbreak of World War III. A top front-page news story (Auberon Waugh, Scourge of the Ways of the World, Dies at 61) propelled its readers on a five-page binge-tour of his life and work, complete with portraits, obituaries, quotations, adoring reminiscences and amused commentaries. A. N. Wilson, in a piece entitled

Why Genius Is the Only Word to Describe Auberon Waugh, put down a marker for his immortality:

He will surely be seen as the Dean Swift of our day, in many ways a much more important writer than Evelyn Waugh. Rather than aping his father by writing conventional novels, he made a comic novel out of contemporary existence, and in so doing provided some of the wisest, most hilarious, and it seems an odd thing to say some of the most humane commentary of any contemporary writer on modern experience.

I was pleased by these sentiments, even though Wilson's use of the word important spoils the thing a little. My father, who spent his life vigorously lobbing brickbats at the whole muddled notion of importance, would have laughed at the idea of himself as an important writer.