Contents

Guide

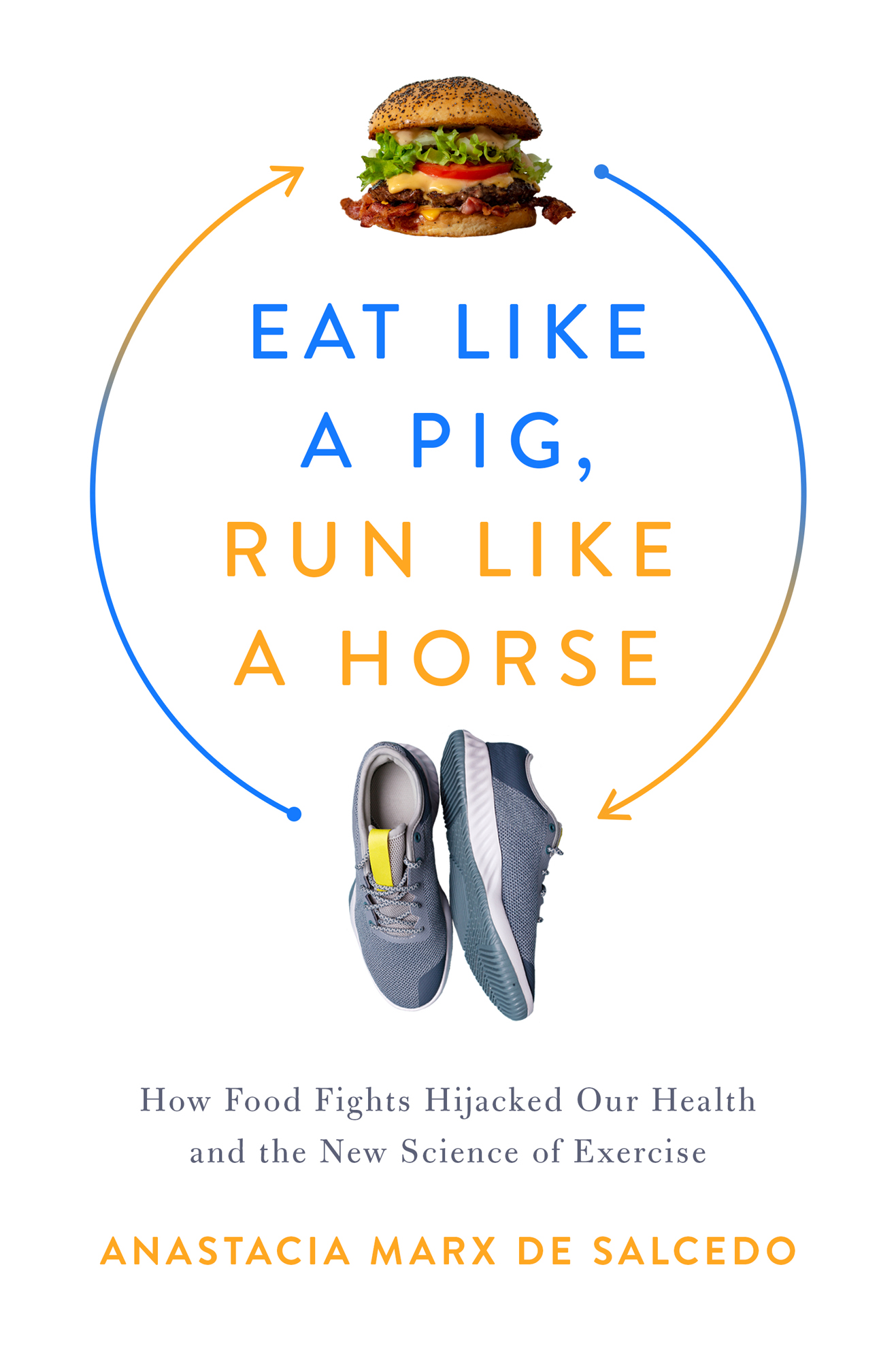

Eat Like a Pig, Run Like a Horse

How Food Fights Hijacked Our Health and the New Science of Exercise

Anastacia Marx de Salcedo

To the animals, who help us see

Chants Democratic

Me imperturbe,

Me standing at ease in Nature,

Master of all, or mistress of allaplomb in the midst of irrational things,

Imbued as theypassive, receptive, silent as they,

Finding my occupation, poverty, notoriety, foibles,

crimes, less important than I thought;

Me private, or public, or menial, or solitaryall these subordinate, (I am eternally equal with the bestI am not subordinate;)

Me toward the Mexican Sea, or in the Mannahatta, or the Tennessee, or far north, or inland,

A river-man, or a man of the woods, or of any farm-life of These States, or of the coast, or the lakes, or Kanada,

Me, wherever my life is lived, O to be self-balanced for contingencies!

O to confront night, storms, hunger, ridicule, accidents, rebuffs, as the trees and animals do.

Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass

Foreword

B eing physically active is good for all ages. Allowing young kids to be physically active can set their habit of lifelong exercise. Being physically active in youth and as an adult reduces your risk of having any of the more than forty chronic diseases, for example, heart attacks, some cancers, type 2 diabetes, and others. Delaying chronic diseases lengthens your healthspan (the length of life before your first chronic disease). Also, being physically active could delay or even keep you out of a wheelchair in a nursing home. Finally, it reduces your chances of being depressed, making your life happier.

Frank W. Booth, PhD, Professor, University of Missouri

Preface

L ast November, on a Staples run for office and school supplies, I pulled into the parking lot and immediately noticed a small flock of Canada geese standing in the middle of traffic, honking, all heads turned to the roof of the box store. I looked up. Pattering along the edge of the building was a fledgling. She teetered on the cornice, then picked her way west. The group, heedless of the jostle of cars in the access road, waddled after her, calling anxiously. I jumped out of my minivan and walked amid them, planting myself like a large CAUTION sign in the stream of vehicles. The fledgling halted at the far end of the roof. The geese cried in unison: Come! Just flap your wings! She strolled back to her original spot, but didnt move. Neither did I. I felt their heartbreak as keenly as if it were my own. I pictured them migrating together, the V formation alighting on top of the mall, and afterward, the young bird, for whatever reasoninjury, fatigue, or fear, unable to continue. Eventually, I left. (Although Id briefly fantasized about insisting that the Staples manager let me out on their roof.) But the image haunted me for the rest of the day and beyond. Did they save her?

When I first began this book, I decided to look at human metabolism, health, and disease through the lens of animals as a way to find a new perspective on a topic that has been examined innumerable times from an anthropocentric one. I think this approach allowed me to have fresh insights and make new linkages, but as time went on, it did something bigger: it made me feel more aware of animals and our relationship with them. On the other end of three-hundred-odd pages, I find myself quickly and utterly absorbed in watching two butterflies dance through cedar brancheswhy do they move that way and together?or a bee crawling over a tiny pile of dirt into a hole in a railroad beamwhat is she doing and where is she going?and pulling to the curb to let my youngest daughter, Mariela, rescue a bunny that has become paralyzed with fear in the middle of the street. I hope some of the stories in this book will make you appreciate our fellow inhabitants of Planet Earth (even) more, especially ones, such as parasitic worms and bats, that often dont get a lot of human love.

When I describe Eat Like a Pig, Run Like a Horse to people, I often call it a crazy mix of personal narrative (many of the names and some details in these sections have been changed to protect privacy), journalism, and very easygoing science writing. There are reasons for all three of these things. I hope that knowing who I am, why Im interested in things, and the connections I make between them encourages you to accompany me on my journey. This is also a feminist decision, since it is the opposite of the authoritative and disembodied third person, a distancing tradition that is sometimes used to cloak the (male) writers intentions and (patriarchal) power. I have fully indulged my aversion to quotations that are just a couple of phrases or sentences. The reason? I like people to speak for themselves. Before interviews, I brief myself thoroughly on their background and topic, so our conversation is about their particular expertise. My job is to be the conduit; quoting long passages allows each of these fascinating people to present themselves and their ideas directly to you. And finally, to make the science comprehensible to everyone, Ive kept those sections extremely simple and in laypersons language. If you want to reconstruct my (extensive) research, all sources are listed in the bibliography. I am also happy to explain the concepts and arguments in more detailjust write.

No book introduction would be complete without acknowledgments. I am blessed to have both an amazing editor and agent who wholeheartedly supported my creativity and experimentation. Thank you so much, Jessica Case and Stephany Evans, for taking risks with me. Im appreciative of the busy scientistsLaurie Goodyear, Darrell Neufer, and Michael Sturekwho took the time to review some of my science passages. Jessica LeTourneur Bax braved my misuse of hyphens and dashes and gently corrected some descriptions and terms. Derek Thornton enriched the book with a semaphoric cover and Maria Fernandez, with comfy interior pages. I am also very grateful for the encouragement and friendship of my writing buddy, Rebecca Lemov. Finally, thank you to my family for tolerating having some of our most intimate moments made public and for making every one of my days an adventure.

1 Poster Child for Multiple Sclerosis

O n a sunny, spring day in April 1991, I woke up in the South End railroad apartment I shared with my boyfriend of five yearsinseparable since Columbia Collegefretting about work. Should I check one more time with the Boat and Recreation Vehicle Registration and Titling Bureau to see if they had the total number of 1990 boat licenses yet? Not having the latest years information would make my report look outdated before it had even been printed. But if they did, Id have to do a whole new economic impact analysis.

Our coffeemaker gave a final gurgle in the kitchen, and then Mack appeared with two steaming cups. He set his on the bureau as he dressed: button-down shirt, brown chinos, sweater. Our brick buildingmost distinguishing feature, a faded 1960s-era, black-and-yellow fallout shelter signwas a forty-five-minute walk and subway ride from the Harvard University Department of Mathematics where he was writing a computer program to model Riemann surfaces for a professor.

Working from home again? Mack asked, sipping his coffee. For the past couple weeks, Id been holed up in our apartment writing a strategic plan for the Massachusetts maritime industry, a project I was doing for my research support staff job at Harvard Business School.