Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

T R O U B L E D W A T E R

T R O U B L E D

W A T E R

A Journey Around the Black Sea

J E N S M H L I N G

Translated from the German by Simon Pare

First published in English in 2021 by

The Armchair Traveller

4 Cinnamon Row

London SW11 3TW

www.hauspublishing.com

@HausPublishing

Originally published under the title Schwere See

Copyright 2020 by Rowohlt Verlag GmbH, Hamburg / Germany

Translation copyright 2021 by Simon Pare

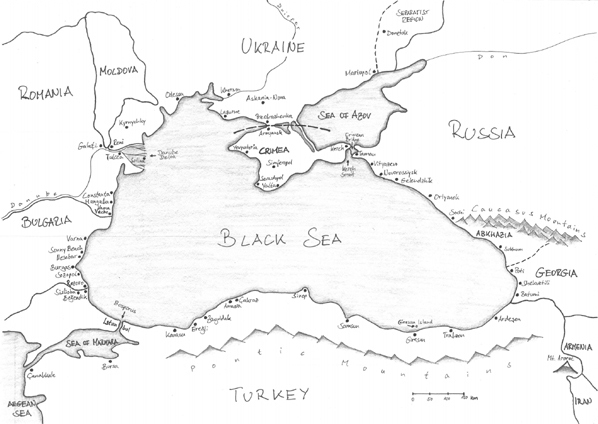

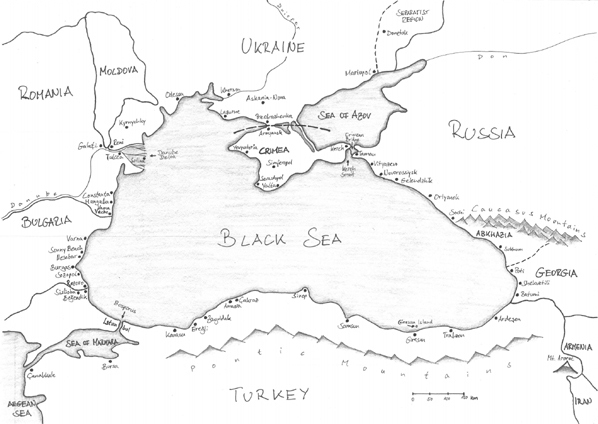

Map copyright Jens Mhling

Extract from Southern Adventure by Konstantin Paustovsky translated by

Kyril Fritz-Lyon

Extract from The King by Isaac Babel translated by Peter Constantine

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-913368-26-5

eISBN: 978-1-909961-77-7

Typeset in Garamond by MacGuru Ltd

Printed in the UK by TJ Books Limited

All rights reserved.

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut

For Seyma

Denizkzm benim

The Flood

Prologue

It seemed to him that the Black Sea

had risen to the skies, to come

pouring down on the earth

for forty days and forty nights.

Konstantin Paustovsky, The Colchis, 1934

We saw them coming towards us as we travelled the last few miles to Mount Ararat, in eastern Anatolia, where Turkey borders Armenia and Iran amid endless slopes of scree. They were walking along the sides of the road in small groups men, most of them young with dark beards and nothing in their hands, except for a few carrying small plastic bags. It was March, and snow still lay on the winding pass roads. I wondered how fast you would have to walk in these mens thin jackets if you didnt want to freeze.

Mustafa, whose taxi Id got into in Agri because the next bus to Dogubayazit left only the following day, motioned with his chin to the walkers beyond the windscreen.

Pasaport yok, para yok.

No passport, no money.

I looked at him quizzically. Syrians?

He shook his head. Afganlar.

They must have come to Turkey via Iran, I thought.

Mustafa nodded as if he could read my mind. Afghanistan Iran Istanbul. He was silent for a moment before a grin splayed his moustache. Istanbul Almanya! he said, suggesting that the Afghans intended destination was my home country.

The moustache hardened into a line when I tried to persuade Mustafa to stop the car. I wanted to talk to the refugees and ask them what they needed, even if Id almost certainly be unable to provide it. Forget it, said Mustafas frozen moustache. Not for all the lira in the world.

We drove on towards Mount Ararat, which has an ancient and enigmatic bond with the Black Sea. Again and again, men would come around a bend in the road, in twos, five at once, then none for a long time, then suddenly a dozen followed by another dozen and for a moment I was convinced that the road beyond the next bend would be black with people. But then no one else appeared for ages.

Every time a bunch of men approached us out of the distance, Mustafa would briefly take his hands off the steering wheel, turn his palms to the sky, and shake his head in silent bemusement, as if he were asking himself, or me, or maybe God, what on earth was to be done with all these people who could not stay where they were.

* * *

Ive seen the Black Sea from all sides, and from none of them was it black.

It was silvery as I drove along the deserted beaches of the Russian Caucasus coast in the spring, as silvery as the skin of the dolphins hugging the shore as they pursued shoals of fish northwards.

It turned blue in May as I reached Georgia, the ancient Colchis of Greek legend, where the beaches are black but not the water.

In Turkey it seemed to take on the green of the tea plantations and hazelnut groves along its shores, and it was still green when I reached the Bosporus in late summer.

The first storms of autumn coloured it brown as the birds headed south and the tourists headed home over the Bulgarian coast.

In Romanias Danube delta the sky seemed to hang so low over the sea that its lead-grey colour rubbed off on the water.

When I reached Ukraine, the waves scraped dirt-grey ice along the beaches.

Only in Crimea did the winter sun brighten the sea again, and here it assumed the hue it will forever have in my memory a cloudy, milky green, like a soup of algae and sun cream.

* * *

Journeys seldom start where we remember their starting. This one may well have begun under my blind grandmothers dining table.

Occasionally, as the grown-ups traded their grown-up stories, my sister and I would crawl between their legs to the end of the table, where Grandma sat. We would creep up quietly behind her chair. The back was wickerwork, the holes big enough for us to poke our fingertips through. We would prod Grandma in her bony back and, although she had heard rather than seen us coming, she never failed to greet our recurring prank with an indulgent, horrified shriek.

Oh, are those mice I can feel?

Squeaking, we would pull our mousy fingers out of the back of the chair and scuttle back under the table.

In Neunkirchen, the small town in the Siegerland area of western Germany where my grandmother lived until her death, stands a memorial:

JOH. HEINRICH VON KINSBERGEN

LIEUT.-ADMIRAL

BENEfACTOR Of THE POOR

* 1.5.1735 22.5.1819

The admirals name or, rather, not his name but his title cropped up from time to time in the grown-up conversations on which my sister and I eavesdropped from under the table. The Admiral stuck in my childhood memory like some kind of semi-mythical character. From what I could grasp, he was a distant relative of ours, a great-great-great-great-great-grandfather who had pitched up in Holland back in the mists of time and acquired considerable fame and wealth there as a seafarer. He had left part of his vast fortune as a fund that, on request, offered grants to impoverished family members back home in the Siegerland. In my imagination, The Admirals money that the adults occasionally mentioned in Neunkirchen took on the proportions of a pirates treasure trove, a glittering stash of gold coins just waiting to be discovered by me, The Admirals legitimate heir.

I was to find out from my aunt Gertraude and her Neunkirchen friends Elfriede and Ingeborg at a family Christmas many years later that I wasnt the only one with his eye on The Admirals money. In my grandmothers hometown there is, besides the memorial to the seafarer, a street called the Van Kinsbergen Ring. Local people call it the potato bug ring in view of the amazing number of needy Neunkircheners who came crawling out of the woodwork after van Kinsbergens death, claiming to be related to the generous admiral. His alleged descendants had multiplied like potato bugs.

That Christmas, Gertraude, Elfriede, and Ingeborg also told me that the legacy payments from Holland had dried up long ago my treasure trove had apparently been confiscated as reparations after the Second World War.