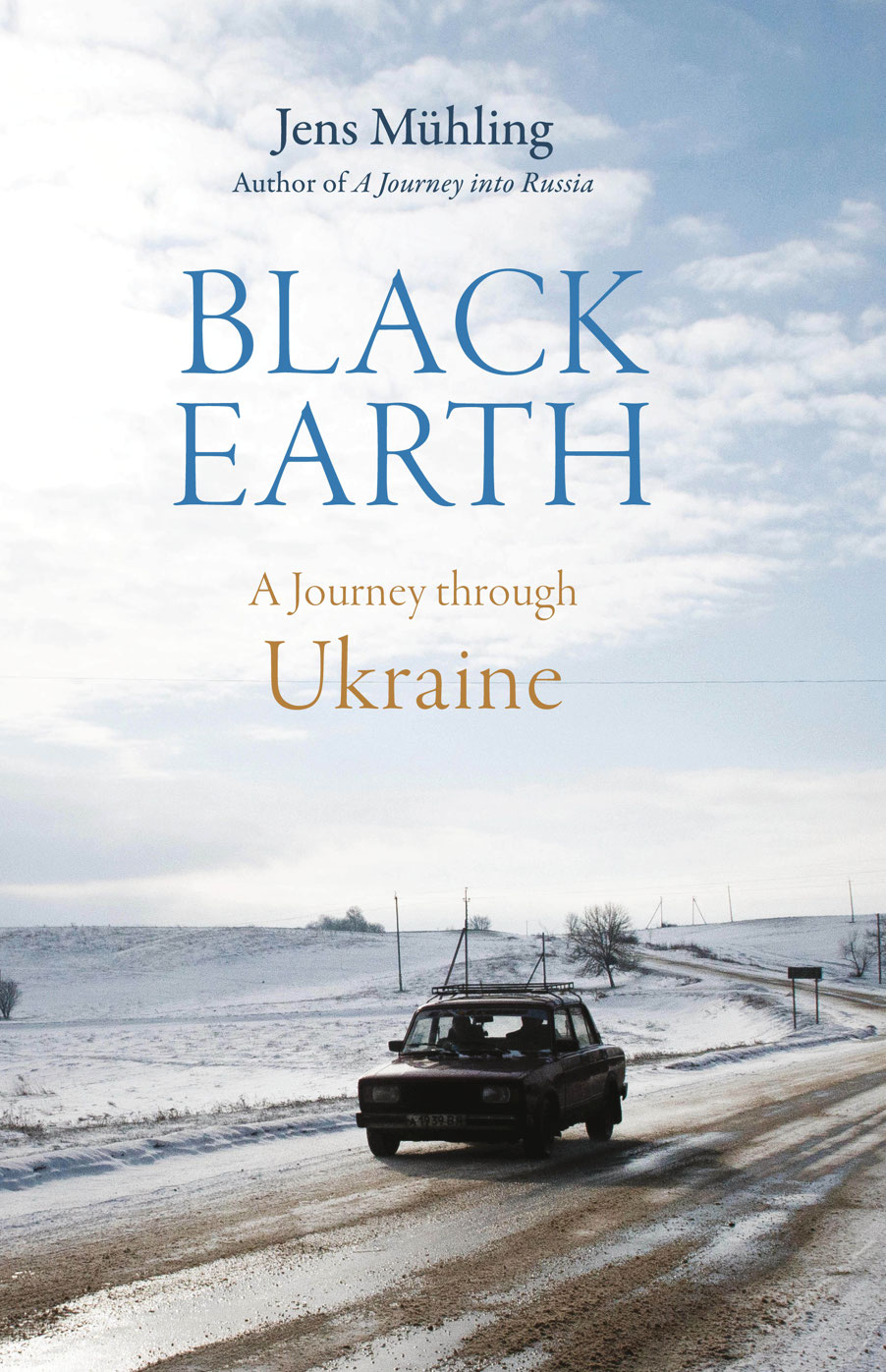

Jens Mühling - Black Earth: A Journey through Ukraine

Here you can read online Jens Mühling - Black Earth: A Journey through Ukraine full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Haus Publishing, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Black Earth: A Journey through Ukraine

- Author:

- Publisher:Haus Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Black Earth: A Journey through Ukraine: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Black Earth: A Journey through Ukraine" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Black Earth: A Journey through Ukraine — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Black Earth: A Journey through Ukraine" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

First published in English in 2019 by

The Armchair Traveller

4 Cinnamon Row

London SW11 3TW

Originally published under the title Schwarze Erde

Copyright 2016 by Rowohlt Verlag GmbH, Reinbek bei

Hamburg

Translation Copyright 2019 by Eugene H. Hayworth

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-909961-60-9

eISBN: 978-1-909961-61-6

Typeset in Minion by MacGuru Ltd

Printed in the UK by TJ International

All rights reserved.

www.hauspublishing.com

Will anybody pay for the bloodshed?

No. No one.

The snow will just melt, the green Ukrainian grass

will grow and carpet over the earth, lush crops

will sprout, the air will shimmer with heat above

the fields, and no traces of blood will remain.

Mikhail Bulgakov, The White Guard, 1925

IN THE THREE YEARS that have passed since I wrote this book, many things in Ukraine have stayed the same.

The war that I witnessed when I travelled through the Donbass in the autumn of 2015 is still going on. Until this day, the Ukrainian army is fighting s eparatist r ebels and their Russian backers in the east of the country. Still there are regular skirmishes in which people die, although these casualties mostly go unreported in the western media, as the state of emergency in Europes east has by now become the norm. The UN registered approximately 13,000 death casualties by April 2019, including more than 3,000 civilians. Around one and a half million people are reported to have fled their homes due to the conflict. As peace talks drag on, everything seems to suggest that the Donbass will remain an unstable region for the foreseeable future, with its status unresolved.

Not much has changed for Crimea either. The Kievan government still regards the Black Sea peninsula as Ukrainian territory while the government in Moscow sees it as a part of Russia. The sanctions which the West imposed on Russia after the annexation are still in force. Thousands of Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars have fled the peninsula, and the remaining part of the Tatar minority still suffer the same repressions that my informants in Crimea complained about in the autumn of 2015. Just as with the Donbass, it is difficult to imagine how Russia, Ukraine and the West are to reach an agreement about Crimeas future.

Internally, too, Ukraine is still characterised by the same conflicts I witnessed on my travels. For the most part, the new regime in Kiev has been unable to fulfil its supporters high expectations, even though one central and important aim of the Maidan Movement has been achieved in negotiations with the European Union: in June 2017, Ukrainians were granted the right to travel visa-free throughout the Schengen Area for a period of up to ninety days. Still, Ukraine remains one of the poorest, most corrupt, and worst administrated countries in Europe, and due to its ongoing territorial conflicts, the prospect of EU or NATO membership seems even less feasible now than before the Maidan Revolution.

Parts of society resign themselves to these disappointments, while others radicalise. A number of political murders have rocked the country in recent years, and repeatedly there have been worrying demonstrations of power by extreme right-wing groups. That the latters political influence is not remotely as great as Russian propaganda would have us believe is a different story.

That, in short, is the state of the news. It is more difficult to summarise what has been going on beyond these headlines. The lives I describe in this book have continued, and while in some cases I know the sequel, in others I dont. Some of the people I met on my journey will have had children, others may have died. Some will still live at the same address, others could have moved. Some will have fallen in love, others may have split up, some will be happier than they were when we met, others not.

I hope, however, that all the stories of life and of grief and of love that I made the focus of my book will still help to make Ukraine understandable as a country when the headlines have long turned their focus elsewhere.

Berlin, April 2019

A QUESTIONING LOOK at the Przemyl bus station, accompanied by words whose meaning I can only guess, I do not speak Polish.

I reply in Russian, accompanied by gestures pointing east: That way, across the border, to Ukraine.

The man, standing idly beside the bus, nods with a knowing expression, as if he understood more than I have said. He is fat and sweaty and no longer young, his eyes are blurred behind streaky glasses, it is a blazing hot day in late summer. I do not know what he wants from me. At first, I mistook him for the bus driver, but he showed no interest in the ticket I held out for him. Apparently, he just wants to talk, and, paradoxically, the fact that I do not speak his language seems to make me the most qualified listener. The less someone understands, the more there is to explain.

I have stashed my backpack on the bus, which is set to depart for Ukraine in a few minutes. The man fills this brief time span with a monologue in which I can only make out Polish sibilants and historical references: Franz-Josef Hitler Stalin cossacks Ukraine Tsar Napoleon Moscow Kremlin Lemberg catholic orthodox

As he speaks, he punctures the air between our faces with his forefinger. He directs my gaze to the old Polish fortress rising in the distance above the roofs of Przemyl. The next moment he urgently points at church towers and then at things that are hidden from my view, which seem to connect the past in his mind with the present before our eyes. I nod, smile, follow his pointing finger, without understanding much.

When the bus finally departs, the man remains at the station, as idle as before. As I watch his corpulent silhouette fading in the distance, I wonder what force of nature makes some people so obsessed with the past, and whether I attract such people because they sense I am looking for history, looking for stories.

Hardware stores, garden centres, tyre depots and spare-parts dealers slip past the bus windows. Between commercial buildings and parking lots, Poland comes to an end. Further on, not far away now, lies the western part of a country in whose east there is war. A war that is being waged about the past, or so it has seemed to me as I have followed the course of events in recent months. Often the mutual battle cry sounded to my ears like the monologue of the man at the bus station, a history-obsessed crescendo of Slavic sibilants and historical reproaches: Lenin! Bandera! Holodomor! Holocaust! Gulag! Galicia! Communists! Fascists! Imperialists!

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Black Earth: A Journey through Ukraine»

Look at similar books to Black Earth: A Journey through Ukraine. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Black Earth: A Journey through Ukraine and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Jens Gustedt [Jens Gustedt] - Modern C](/uploads/posts/book/146099/thumbs/jens-gustedt-jens-gustedt-modern-c.jpg)