Copyright 2016 by Sophie Pinkham

First American Edition 2016

First published in Great Britain under the title

Black Square: Adventures in the Post-Soviet World

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Fearn Cutler de Vicq

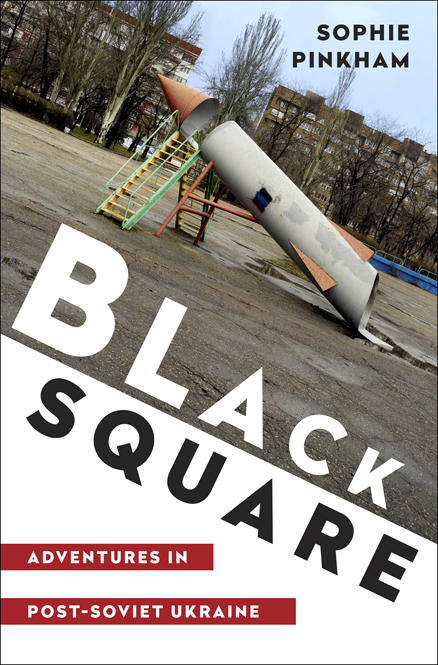

Jacket design by Patti Ratchford

Jacket photograph by Iva Zimova / Panos Pictures

Production manager: Louise Mattarelliano

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Pinkham, Sophie, author.

Title: Black square : adventures in post-Soviet Ukraine / Sophie Pinkham.

Other titles: Adventures in post-Soviet Ukraine

Description: First American edition. | New York : W.W. Norton & Company,

[2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016031600 | ISBN 9780393247978 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: UkraineSocial life and customs21st century. |

UkraineHistory1991 | UkrainePolitics and government1991

Classification: LCC DK508.847 .P55 2016 | DDC 947.7086dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016031600

ISBN 978-0-393-24798-5 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

CONTENTS

ABOVE ALL, I am profoundly grateful to the Ukrainian and Russian friends, colleagues, and acquaintances without whose hospitality, generosity, and kindness this book would never have existed. I am also thankful to my colleagues in the international harm reduction and drug policy movements, who taught me so much and gave me many opportunities to explore.

I was lucky to benefit from the insight, close reading, dedication, and encouragement of my excellent editors, Tom Avery at Heinemann and Tom Mayer at Norton. I was also fortunate in my agent, Zo Pagnamenta. Christopher Cumming, Jeremy Kessler, Orysia Kulick, and Julia Yatsenko provided helpful comments and invaluable moral support. Keith Gessen at n+1 solicited several articles on Ukraine that later grew into this book. At Columbia University, Boris Gasparov and Tatiana Smoliarova introduced me to many of the literary themes and figures discussed here.

I owe a special debt to my wonderful parents, who instilled in me a lifelong love of literature and supported my sometimes mystifying journeys to foreign lands.

The Institute for International Education provided the grant that allowed me to live in Ukraine for an extended period, and the International Research and Exchanges Board supported my time in Irkutsk.

Short portions of this book stem from articles written for Foreign Affairs,n+1, The Nation, and The New Yorker. I am grateful to the editors and other staff who worked with me at those publications.

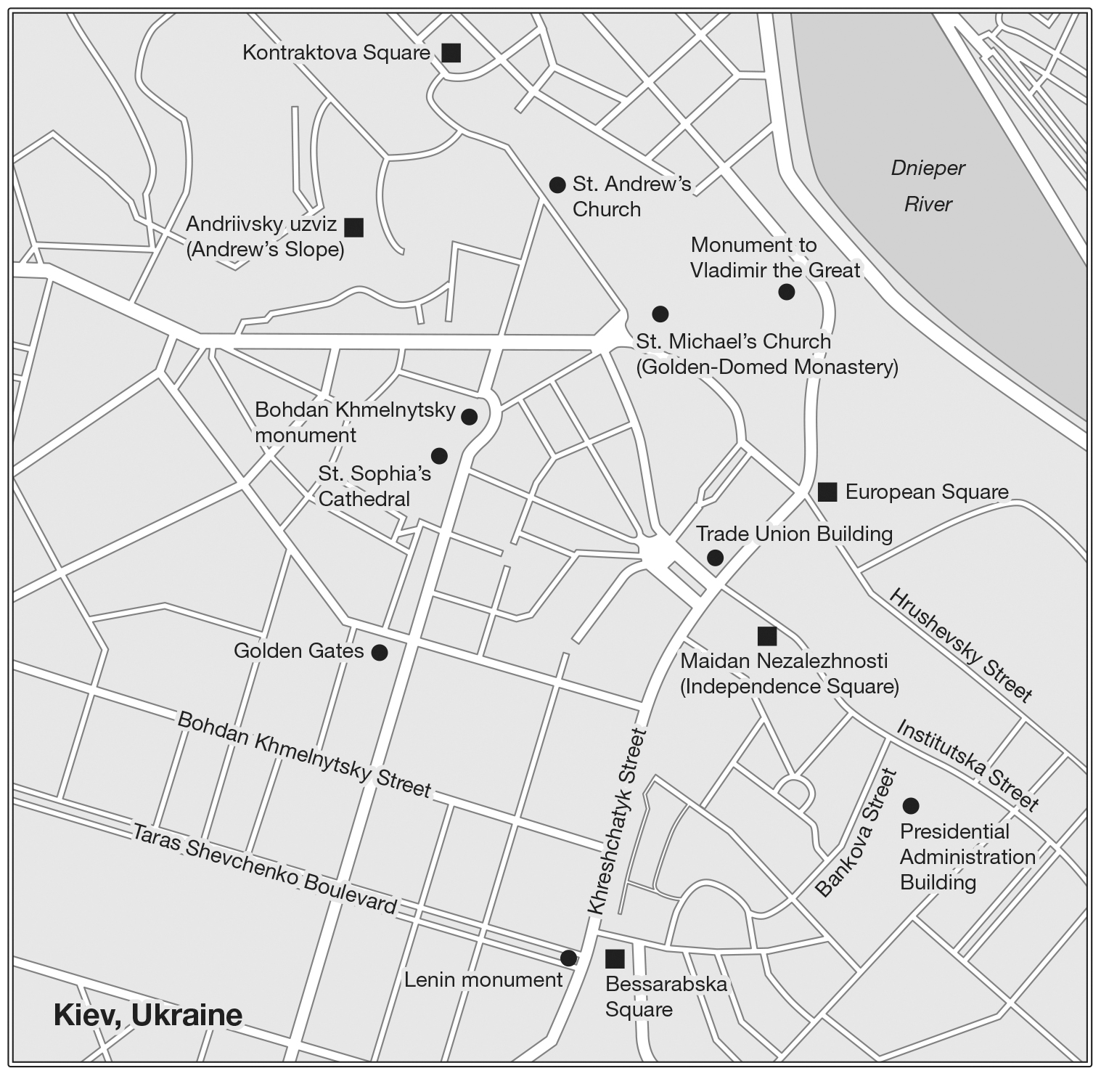

T here are several ways of transliterating Ukrainian and Russian words. (The two languages use slightly different Cyrillic alphabets.) In the interest of legibility, I have used simplified versions of the Library of Congress transliteration systems. When someone has a clear preference about how his or her name should be transliterated, I have used that spelling (e.g., Klitschko rather than Klichko). In cases of personal names that have the same Cyrillic spelling in Russian and Ukrainian and are recognizable to English readers, I have chosen the familiar spelling rather than the Ukrainian transliteration (e.g., Igor rather than Ihor). For the names of places in contemporary Ukraine that have slightly different names in Russian, I have used the Ukrainian names and transliterations (e.g., Lviv rather than Lvov, Dnipropetrovsk rather than Dnepropetrovsk), except in the case of Kiev (rather than Kyiv) and Odessa (rather than Odesa), where I have chosen to use the spellings long familiar to English speakers.

I was seven years old when the Berlin Wall fell. Watching the news with my parents in New York, I wondered how a simple concrete barrier could be so important. Why hadnt people just climbed over it? Newscasters discussed the Iron Curtain, which sounded scary, but also confusing. Didnt curtains, by definition, ripple and fold?

I was sixteen when NATO bombed Yugoslavia during the Kosovo War. I assumed that Clinton had good reasons for intervening. Despite his sexual indiscretions, our president seemed like a kindly, paternal figure. At school I knew a nice Serbian boy who wrote poetry; he and his brother got into fights with the Albanian kids on the basketball court, but I couldnt quite understand why. Anyway, we were teenagers; we had better things to think about.

I graduated from high school in the year 2000. A year earlier the seniors had chanted ninety-nine; as we celebrated that June, my friends and I chanted zero and laughed. Panic about Y2K had come to nothing; the world hadnt ended with the old millennium. But disaster arrived the next year. From her high school classroom in downtown Manhattan, my younger sister saw two planes hit the Twin Towers. She and her classmates watched tiny figures leap from the burning buildings. Outside, FBI agents told the students, Dont look back, and run: north, away from the fast-moving cloud of dust and death. Soon the United States was fighting a war, and then a series of wars, that became the permanent backdrop to our young adult lives.

It was an inauspicious start, and I often wished Id been born in some other decade. But I had the idealism and longing for adventure common among young people. I wanted to fix something, to help someone. AIDS had gotten its name in the year I was born, and I had grown up with its threat; in high school and then in college, I volunteered with health groups. On a whim, I studied Russian. After college I applied to volunteer at the Red Cross in Siberia, in search of something I could not yet name.

My choice of destination, however haphazard, was deeply appropriate. When I arrived in Russia, the young countries of the former Soviet Union were still struggling to establish their places in the world, to define their identities. In Russia, as in the United States, the year 2000 had lived up to its millennial billing. It was the end of the 1990s, which had been a time of chaos, hope, and violence, and the beginning of the Putin era. Russias new president stood for stability and prosperity, and he had wide support; in 2004, in Moscow, I was surprised to see Russian girls my age carrying Putin key chains. But this perceived stability came at the price of the civil liberties promised by the collapse of the USSR, and Russia was becoming an increasingly authoritarian state. In other countries of the former Soviet Union, the future looked brighter: color revolutionsGeorgias 2003 Rose Revolution, Ukraines 2004 Orange Revolution, Kyrgyzstans 2005 Tulip Revolutionpromised peaceful transitions to democracy led by activists, students, idealists.

After Siberia I got a job working for George Soross Open Society Institute, a foundation dedicated to promoting democracy and civil society in the former Soviet Union (or overthrowing anti-Western governments, depending on your perspective; blamed for the color revolutions, the Open Society Institute was pushed out of Russia and authoritarian Uzbekistan). I met activists who were only slighter older than I was, members of the first generation to come of age in a post-Soviet world. In 2008 I moved to Ukraine, where I became close friends with many other members of this generationnot only activists but doctors, musicians, artists, teachers.

Next page