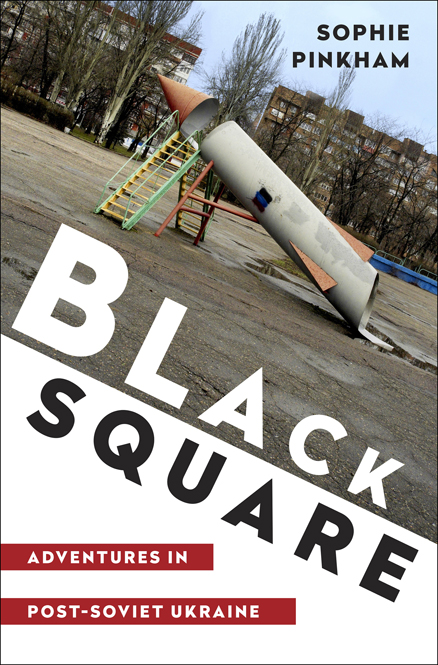

Sophie Pinkham - Black Square: Adventures in the Post-Soviet World

Here you can read online Sophie Pinkham - Black Square: Adventures in the Post-Soviet World full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: Random House, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Black Square: Adventures in the Post-Soviet World

- Author:

- Publisher:Random House

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Black Square: Adventures in the Post-Soviet World: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Black Square: Adventures in the Post-Soviet World" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Black Square: Adventures in the Post-Soviet World — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Black Square: Adventures in the Post-Soviet World" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CONTENTS

For my friends in Ukraine and Russia,

with love and gratitude.

I was seven years old when the Berlin Wall fell. Watching the news with my parents in New York, I wondered how a simple concrete barrier could be so important. Why hadnt people just climbed over it? Newscasters discussed the Iron Curtain, which sounded scary, but also confusing. Didnt curtains, by definition, ripple and fold?

I was sixteen when NATO bombed Yugoslavia during the Kosovo War. I assumed that Clinton had good reasons for intervening. Despite his sexual indiscretions, our president seemed like a kindly, paternal figure. At school I knew a nice Serbian boy who wrote poetry; he and his brother got into fights with the Albanian kids on the basketball court, but I couldnt quite understand why. Anyway, we were teenagers; we had better things to think about.

I graduated from high school in the year 2000. A year earlier the seniors had chanted ninety-nine; as we celebrated that June, my friends and I chanted zero and laughed. Panic about Y2K had come to nothing; the world hadnt ended with the old millennium. But disaster arrived the next year. From her high school classroom in downtown Manhattan, my younger sister saw two planes hit the Twin Towers. She and her classmates watched tiny figures leap from the burning buildings. Outside, FBI agents told the students, Dont look back, and run: north, away from the fast-moving cloud of dust and death. Soon the United States was fighting a war, and then a series of wars, that became the permanent backdrop to our young adult lives.

It was an inauspicious start, and I often wished Id been born in some other decade. But I had the idealism and longing for adventure common among young people. I wanted to fix something, to help someone. AIDS had gotten its name in the year I was born, and I had grown up with its threat; in high school and then in college, I volunteered with health groups. On a whim, I studied Russian. After college I applied to volunteer at the Red Cross in Siberia, in search of something I could not yet name.

My choice of destination, however haphazard, was deeply appropriate. When I arrived in Russia, the young countries of the former Soviet Union were still struggling to establish their places in the world, to define their identities. In Russia, as in the United States, the year 2000 had lived up to its millennial billing. It was the end of the 1990s, which had been a time of chaos, hope, and violence, and the beginning of the Putin era. Russias new president stood for stability and prosperity, and he had wide support; in 2004, in Moscow, I was surprised to see Russian girls my age carrying Putin key chains. But this perceived stability came at the price of the civil liberties promised by the collapse of the USSR, and Russia was becoming an increasingly authoritarian state. In other countries of the former Soviet Union, the future looked brighter: color revolutionsGeorgias 2003 Rose Revolution, Ukraines 2004 Orange Revolution, Kyrgyzstans 2005 Tulip Revolutionpromised peaceful transitions to democracy led by activists, students, idealists.

After Siberia I got a job working for George Soross Open Society Institute, a foundation dedicated to promoting democracy and civil society in the former Soviet Union (or overthrowing anti-Western governments, depending on your perspective; blamed for the color revolutions, the Open Society Institute was pushed out of Russia and authoritarian Uzbekistan). I met activists who were only slighter older than I was, members of the first generation to come of age in a post-Soviet world. In 2008 I moved to Ukraine, where I became close friends with many other members of this generationnot only activists but doctors, musicians, artists, teachers.

My family and my friends at home had trouble understanding why I had fallen in love with Ukraine, a country that most Americans could hardly find on a map, famous only for Chicken Kiev and mail-order brides. I tried to explain that I loved the dreamlike quality of a place where the resolutely premodernhorse-drawn carts and babushkas afraid of the evil eyesurvived amid the ruins of Soviet utopian modernism, a place that had not yet caught up with the anonymous global marketplace. I was fascinated with life on the other side of the Iron Curtain, in a world that had served for so long as Americas nemesis, the mirror in which the United States confirmed its own identity. And then there was the charm of getting to know a foreign culture, as the unintelligible becomes the startlingly new.

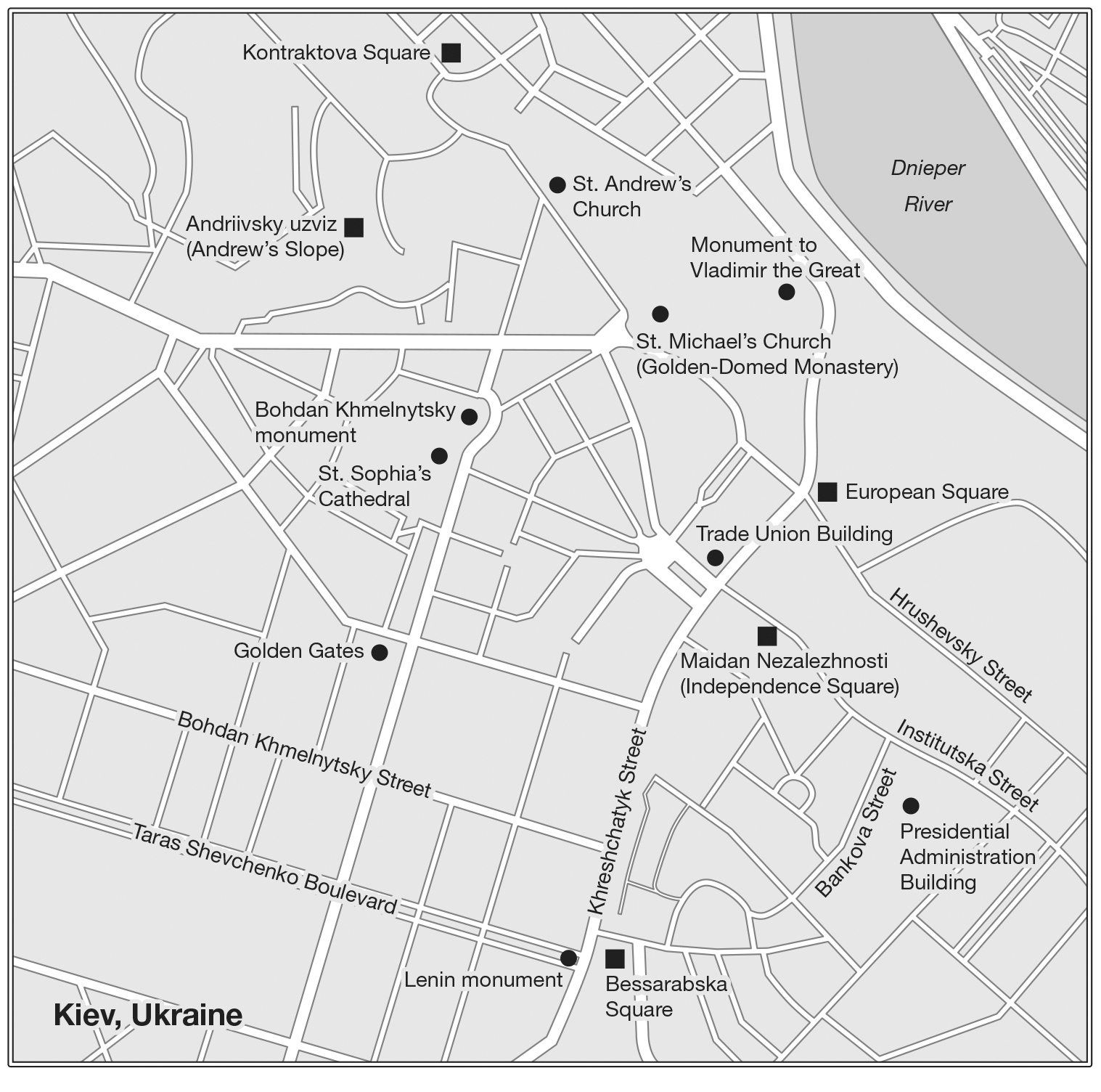

I had already moved back to New York by the winter of 201314, when Ukraine had another revolution. This one wasnt assigned a color; more spontaneous than the Orange Revolution a decade earlier, it came to be known simply as Maidan, for Maidan Nezalezhnosti, Kievs Independence Square, the site of mass protests that lasted for three months and ended with the flight of Ukraines corrupt president, Viktor Yanukovych, to Russia. When I first lived in Ukraine, I was preoccupied with its ideas of the past and future. Once Maidan started, there was nothing but the present; every hour held the possibility of transformation, and of terrible violence.

Before Maidan, I had a lot of stories about Ukraine and about Russia, but I wasnt quite sure how they all fit together. After Maidan, a series of curious adventures became a historical trajectory, and the individual search for meaningmy own, and that of my Ukrainian and Russian friendsbecame a collective one. The Bildungsroman intersected with revolution, as tens of thousands of people converged on Kievs central square.

IN 1915, A CENTURY before Maidan, Kazimir Malevich painted a black square on a white background. When it was first exhibited, the painting hung in the upper corner of the room, the place traditionally reserved, in Russian homes, for a religious icon. The Black Square became the icon of the Russian avant-garde, hanging above Malevichs body when he lay in state in his Leningrad apartment in 1935. (He was lucky to die of natural causes before Stalins 1937 Terror.) Malevich was born to Polish parents near Kiev; his work was influenced both by the black and red patterns of traditional Ukrainian textiles and by the stark black crosses on the garments of Russian saints. Today, like many heroes from the Soviet Union and the Russian Empire, he is claimed by Russians, Poles, and Ukrainians alike.

For Malevich, the Black Square represented the end of time, the culmination of history. He would have liked my high school graduation in the year 2000; for him, truth began at zero. (In 1915 he cofounded a journal called Zero.) His Black Square was meant to evoke the experience of pure non-objectivity in the white emptiness of a liberated nothing. By the time the Russian Revolution and ensuing civil war were over, in 1922, this emptiness of a liberated nothing was painfully real, with everyday life shattered by the conflict between the Red Army and the anti-Communist White Guard.

Over the next decades, the Soviets built a new world, with millions of casualties along the way. But by 1991 the countries of the former Soviet Union found themselves at another zero point, forced to reinvent and rebuild yet again. And then there was Maidan. More than a hundred people were killed during the protests; some ten thousand died in the war that followed. Ukraine and Russia, which supported and prolonged the conflict, descended into paranoia and rage.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Black Square: Adventures in the Post-Soviet World»

Look at similar books to Black Square: Adventures in the Post-Soviet World. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Black Square: Adventures in the Post-Soviet World and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.