ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jan William Smith (1935 ) is a retired journalist who lives in Canberra. His biographical works are The Dark Daughter, the story of the late Gloria Arrow, a woman of South Sea Islander background in Mackay, Queensland; and Mackie and Jack, the story of the late Mary Todd, a prominent sheep and cattle breeder in Queensland and northern New South Wales and her husband, Squadron Leader Jack Todd, who died at Rabaul as a prisoner of war of the Japanese in World War II.

Smith worked in local and Federal Government public affairs, the ABC and daily newspapers in Queensland and Sydney.

Smiths interest in the artist Napier Waller began during his years as a voluntary guide at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

CONTENTS

Copyright Jan William Smith

First published 2022

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission.

All inquiries should be made to the publishers.

Big Sky Publishing Pty Ltd

PO Box 303, Newport, NSW 2106, Australia

Phone: 1300 364 611

Fax: (61 2) 9918 2396

Email:

Web: www.bigskypublishing.com.au

Cover design and typesetting: Think Productions

For Cataloguing-in-Publication entry see National Library of Australia.

Author: Jan William Smith

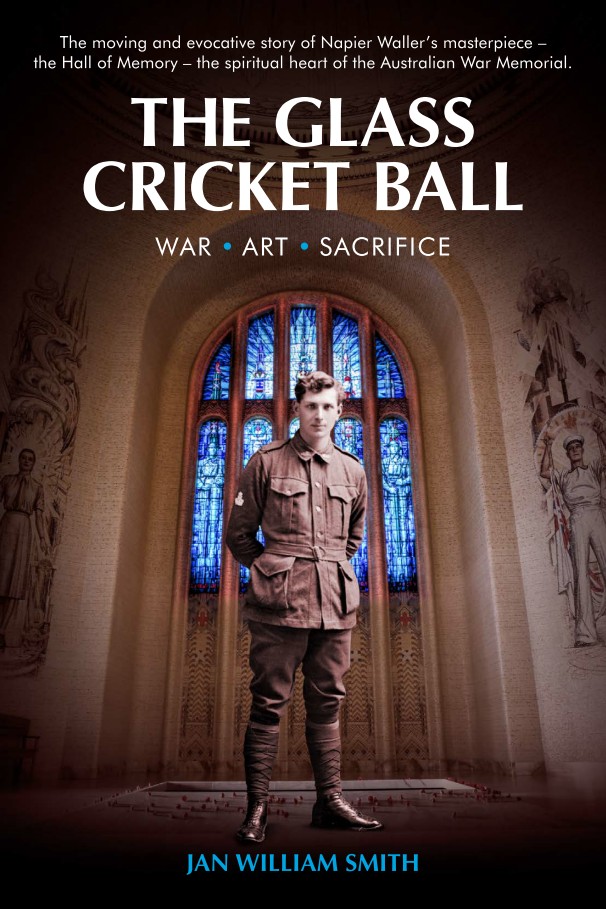

Title: The Glass Cricket Ball: War. Art. Sacrifice

ISBN: 9781922615398

THE GLASS

CRICKET BALL

WAR ART SACRIFICE

JAN WILLIAM SMITH

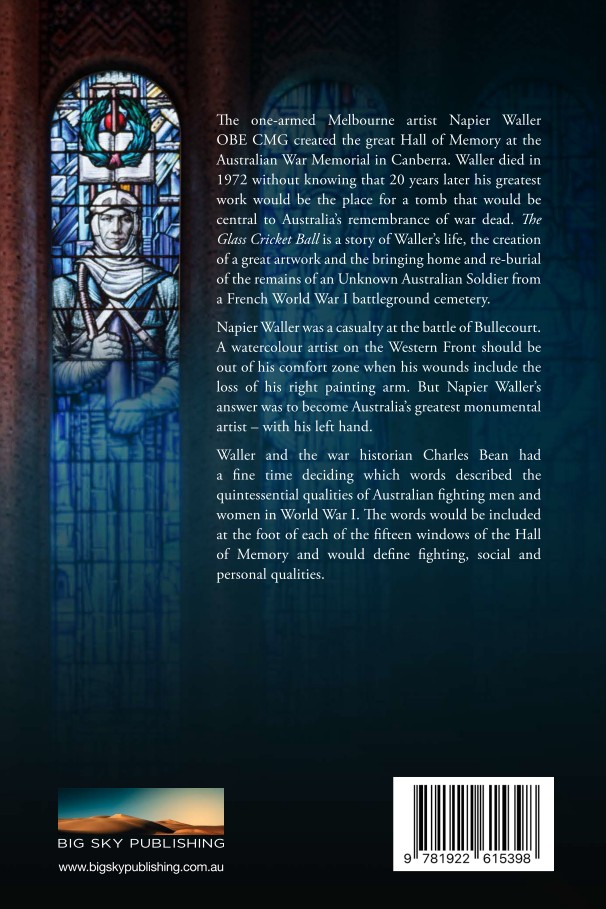

The one-armed Melbourne artist Napier Waller OBE CMG created the great Hall of Memory at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. Waller died in 1972 without knowing that 20 years later his greatest work would be the place for a tomb that would be central to Australias remembrance of war dead. The Glass Cricket Ball is a story of Wallers life, the creation of a great artwork and the bringing home and re-burial of the remains of an Unknown Australian Soldier from a French World War I battleground.

THE GLASS

CRICKET BALL

WAR ART SACRIFICE

JAN WILLIAM SMITH

Table of Contents

ONE

I came for a funeral and a parade. I saw an escorted motor-drawn gun carriage with a coffin and black-plumed horses skittering on the bitumen like girls in tap shoes warming up for a dance. The horses, always part of mans ceremonies and bizarre entertainments, had come for a field marshals funeral. Except there was no field marshal. The burial was for an Unknown Australian Soldier.

It was 11 November 1993 and the funeral of this unknown and perhaps unremarkable man would seem to draw the line under nearly a century of remembrances and commemorations of the wars that have taken more than 100,000 Australian lives since 1914.

And there was the tomb. But before there was the tomb I had been searching for another man the man who created the place for the tomb. He, too, had been an unremarkable soldier. But he was to become a remarkable artist. His name was Mervyn Napier Waller.

***

I had first journeyed to the place where Waller was born in 1893. I knew I was trespassing when I climbed a padlocked steel gate beside the Kolor Road near the little Victorian western district town of Penshurst, but I was not likely to be challenged. The house that had been called Grand View, was no longer there. Now the ground was scattered with pinecones from an ancient Monterey pine that would have stood beside the garden gate of the homestead that had been there 100 years before.

Before me was scattered evidence of the artists childhood, tumbled over, rusting and blowing in the wind. There remained only some stone blocks in rows, where once the bearers of the house had lain. The old pine tree, its bark like the shingles of a giant grey saurian, would have seen the fire that destroyed the house one day in 1977. But by that time the artist who had been a boy there would have been five years dead.

In town, I had talked to the Farrells and had been told the bushfire had started on the Macarthur Road, to the south-west of Penshurst village on a Wednesday night in mid-January and had burned northward through the black soil flats. It was smoking there for days, concealed in the deep cracks in the black earth and smouldering in the tussock grass, with no-one paying much attention. On the Saturday morning the wind returned and the fire was easily fanned into life. It travelled fast through the thick pasture grass down behind the house.

Foyster Farrell, who lived there then with his wife, Ellen, thought it had missed Grand View by at least a quarter of a mile. But in the afternoon the wind changed and there was nothing they could do. The house was built of weatherboard, with a corrugated iron roof. It had not stood a chance. And there was no time to save the pictures.

Oh yes, there were pictures, even then. Before the boy had gone to Melbourne to study his art, there were pictures. In the little house he had begun very early to express himself with mural decoration. He would have read about murals in the books he borrowed. There would be murals in his life and the obvious place for him to start was on the farmhouse walls.

To the people of Penshurst village, the murals were just the fancy of a boy. Some medieval bucolic scenes. When the fire came they were of least concern. Of course, there were those in town who said they had always meant to photograph them because the boy they thought they once knew had become famous. But they had never gone and now they shook their heads as though these were their personal loss.

The Farrells moved into town after the fire, leaving only the tangle of twisted corrugated iron roofing and two brick chimneys pointing skywards like the stiff burned legs of an animal carcass. In time the grass grew over it all, and the wind blew the blackened roof iron away and rolled the two burst corrugated iron water tanks off their stands. The remains of a fallen windmill lay in a rusting tangle.

The young Mervyn Waller had liked living in the stones, as Penshurst people called the land that was littered with ancient volcanic residue. The volcanic soil in the lava country was rich, but when sufficient of the Mt Rouse stones were shouldered out of the way, the boys father could farm scarcely 11 of the 200 acres he had for that purpose. Stone Waller is what William Waller sometimes called himself, which is a clue to how he might have pronounced his own name. The boys mother, Sarah Napier, had come from a line of Scottish Napiers and could trace them back as far as the Magna Carta. One was John Napier, who invented logarithms.