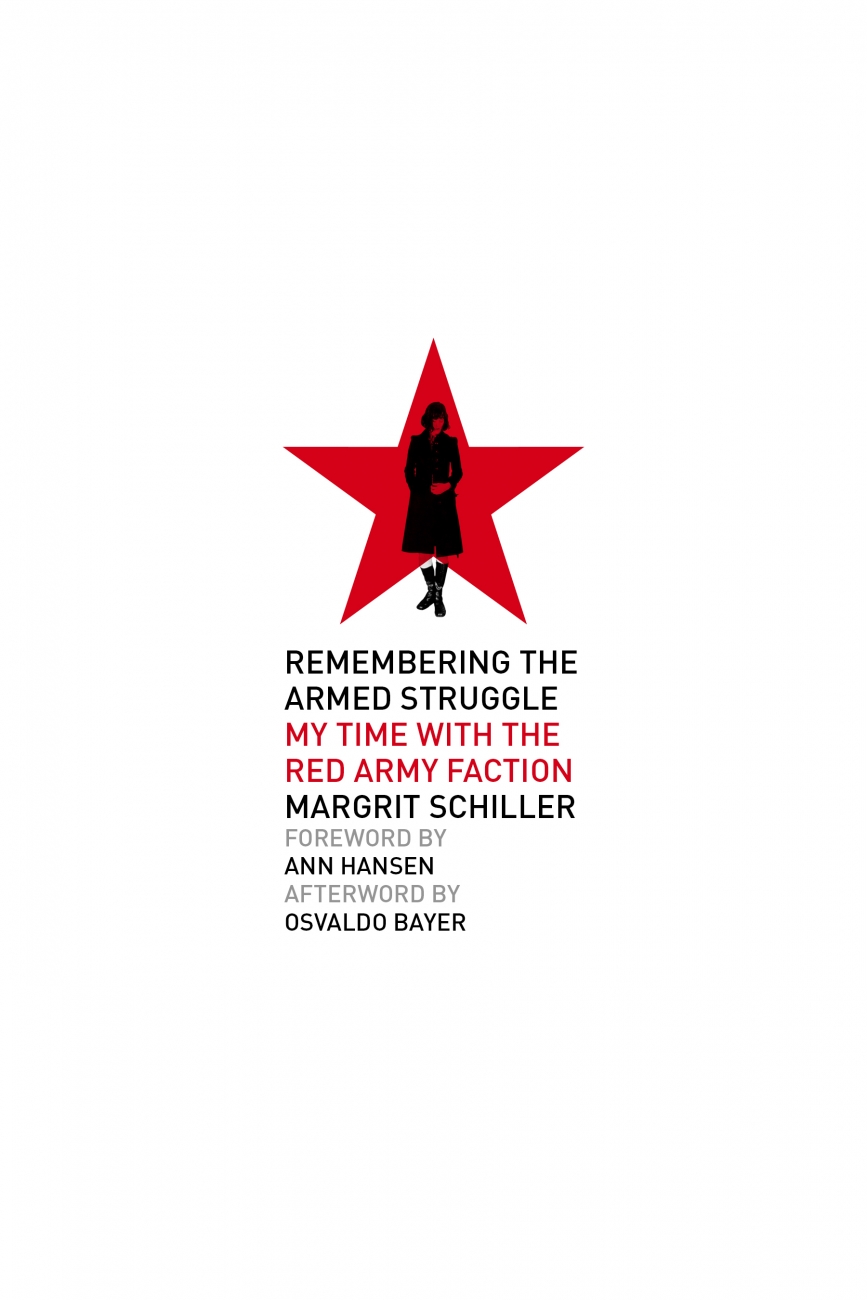

Remembering the Armed Struggle

my time with the red army faction

Margrit Schiller

Remembering the Armed Struggle:

My Time with the Red Army Faction

2021 Margrit Schiller

First published in German by Konkret-Verlag in 1999

Original translation by Lindsay Munro,

edited by Kersplebedeb for this edition

This edition copyright Kersplebedeb, 2021

ISBN: 978-1-989701-11-9

Cover by John Yates / www.stealworks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press

P.O. Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

www.pmpress.org

Kersplebedeb Publishing and Distribution

CP 63560

CCCP Van Horne

Montreal, Quebec

Canada H3W 3H8

www.kersplebedeb.com

www.leftwingbooks.net

For Benita and Nicolas

Acronym Key

BfV: Bundesamt fr Verfassungsschutz (Federal Ofce for the Protection of the Constitution); there is a federal BfV, and each Land also has its own BfV

BKA: Bundeskriminalamt (Federal Criminal Police Office)

BND: Bundesnachrichtendiesnt (Federal Intelligence Service)

CDU: Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (Christian Democratic Union)

GSG-9: Grenzschutzgruppe 9 (Border Protection Group 9)

LKA: Landeskriminalamt (State Criminal Police Office)

MAD: Militrischer Abschirmdienst (Military Counterintelligence Service)

SDS: Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund (Socialist German Student Union)

SPK: Sozialistisches Patientenkollektiv (Socialist Patients Collective)

RZ: Revolutionre Zellen (Revolutionary Cells)

Foreword by Ann Hansen

In the early 1980s, I was part of an anarchist-inspired urban guerrilla group in Canada, known as Direct Action. After our capture and a lengthy trial, I was given a life sentence for my part in our campaign of sabotage. I subsequently spent about seven years in the womens federal prison system in the 1980s and early 1990s, as well as a few short parole suspensions in the twenty-first century.

Based on my experiences, I believe the quality that makes Margrit Schillers memoir so unique is the honesty of her first-hand account, or as people in the 1970s would have said, her ability to tell it like it is.

Remembering the Armed Struggle documents seven years of Schillers life in the 1970s, first in the underground, and then in the prisons of West Germany, as a member of the Red Army Faction, one of the most influential urban guerrilla groups of the twentieth century. In retrospect, I can attribute some of my inspiration at the time of Direct Action to the Red Army Faction, even though I had become disillusioned with their Marxist-Leninist ideology by that point.

Schiller recounts how she first encountered the RAF as a political activist in the Socialist Patients Collective, a radical psychiatry collective. She was unwittingly introduced to the groups founding members when a friend asked if they could use her apartment as a safehouse. Schiller agreed, although she only knew her new roommates by their aliases and before they had begun carrying out public actions.

The narrative unfolds through the prism of Schillers personal experiences, providing a nuanced picture of the RAF. This rare balance rests on the strength of Schillers ability to recount stories as she experienced them at the time; she recalls RAF members laughing at jokes in comic books and listening to rock music in her apartment safehouse, just like anyone else. She describes her experiences in a familiar, nondogmatic style that reflects the fact she was not influenced by preconceived notions about glorified heroes, nor by the vilified urban guerrilla stereotypes portrayed by the mass media.

It is difficult in todays world to imagine the degree of support there once was for urban guerrilla warfare. But the 1960s and 1970s was a time of national liberation movements, often spearheaded by guerrilla fronts that had successfully brought imperialism to its knees: the Chinese Revolution under the guidance of Mao, the Cuban Revolution led by Castro and Che, and the Algerian Revolution, in which Frantz Fanons groundbreaking book The Wretched of the Earth advocated for armed anti-colonial struggle as both therapeutic and effective for a colonized people.

In todays world, even those who support armed struggle in theory may question its value in the absence of a popular revolutionary movement. However, in the 1960s and 1970s, revolutionary collectives, lifestyles, and culture contributed to popular revolutionary movements, even in the heart of the imperialist metropoles. There was no lack of water in which the proverbial fish could swim: the American Indian Movement, the Weather Underground, and the Black Liberation Army in the United States, ETA in Spain, the Red Brigades in Italy, the IRA in Ireland, the FLQ in Quebec, and in West Germany, the Red Army Faction and 2nd of June Movement.

Schillers memoir not only takes place in a historical period of popular resistance to global imperialism, it also unfolds during a time of growing feminist awareness of patriarchal dynamics, not only in the straight world of their parents and society at large, but even among their comrades. Schillers critique of the leadership style of Andreas Baader, one of the RAFs founding members, reflects the experiences of other young female revolutionaries in the Black Panthers and Weather Underground, who were also beginning to incorporate a feminist critique and practice into their movements.

Following her capture, Remembering the Armed Struggle documents Schillers harrowing experiences of almost six years in the isolation and sensory deprivation cells that were the centerpiece of the nascent counterinsurgency prison program in West Germany. It is worth remembering that a number of RAF prisoners would die behind the prison walls, and that the struggles of the political prisoners were often of critical importance to the group. Schiller provides chilling accounts of the groundbreaking psychological torture techniques used to destroy political prisoners: solitary confinement and sensory deprivation, isolated yard time in physical restraints, constant transfers, twenty-four-hour-a day florescent lighting and surveillance, censorship of mail, and interruption of sleep for count and cell searches.

Indeed, her account of her years in West Germanys prison system is like looking through a porthole into the future. In the 1970s, the left was shocked as the West German state unrolled increasingly repressive legislation and prison conditions aimed not only at isolating the political prisoners but at literally destroying them when they dared to resist. Unfortunately, by the twenty-first century, the left has become numb to the slow creep of the same repressive legislation and prison conditions that were once directed solely at political prisoners, but which have now become normalized, targeting any prisoner who refuses to submit.

Schiller and the other political prisoners in West Germany were kept in isolation and sensory deprivation conditions, the extreme form being known as the Dead Wing. Today, there is one prison in the United States that is a stand-alone isolation prison, ADX Florence, in Colorado, but there are at least fifty-seven stand-alone isolation units in prisons across the country. Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines in Quebec is the only stand-alone isolation prison in Canada, but, as in the US, there are many stand-alone isolation units in prisons across this country. In these stand-alone prisons or units, prisoners are held in isolation, often for years at a time, with only one hour of exercise daily and no access to programs of any kind. They are also subjected to 24/7 audiovisual surveillance. The administrative decision to keep prisoners isolated is often not related to their sentences or charges but, rather, to their behavior in the prison, their status as so-called gang members, or their involvement in radical movements. Some of these prisoners could be labelled political prisoners; a disproportionate number are dealing with mental health issues, are racialized, and are being punished for allegedly posing a threat to the good order of the institution.