SOMETIME KIN

SOMETIME KIN

Layers of Memory, Boundaries of Ethnography

Sandra Wallman

First published in 2020 by

Berghahn Books

www.berghahnbooks.com

2020 Sandra Wallman

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wallman, Sandra, author.

Title: Sometime kin : layers of memory, boundaries of ethnography / Sandra Wallman.

Description: New York : Berghahn, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019034512 (print) | LCCN 2019034513 (ebook) | ISBN 9781789203394 (hardback) | ISBN 9781789203400 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Ethnology--Italy--Bellino. | Participant observation. | Ethnology--Fieldwork. | Bellino (Italy)--Social life and customs.

Classification: LCC DG975.B385 W35 2020 (print) | LCC DG975.B385 (ebook) | DDC 945/.13--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019034512

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019034513

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78920-339-4 hardback

ISBN 978-1-78920-340-0 ebook

For my children,

Efua, Simon, Maia and Julian

as they were and as they are

and for W. of course.

Contents

Illustrations

Figures

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Tables

.

.

Acknowledgements

This book is built on the patient hospitality of the Bellinesi and the forbearance of my family. I apologise to anyone who feels themselves misrepresented in it; my hope is that my version of each persons story comes close to what they meant. I thank all of them for the experience described in these pages.

Sometime Kin would not have happened without the encouragement of readers and staff at Berghahn, and the help received from Ralfos Bakolas and Tomoko Hayakawa at various points during the preparation of the manuscript.

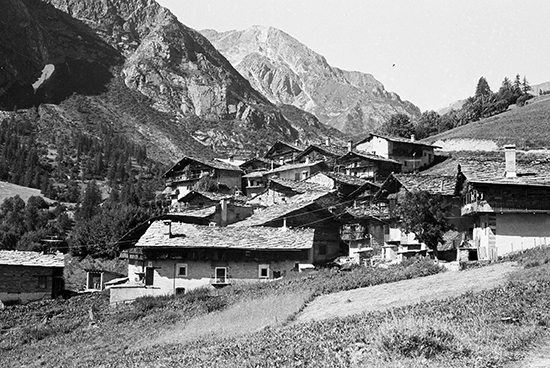

Figure 0.1 Bellino Celle village. Photograph by the author.

Introduction

This book is based on fieldwork which took place many years ago. Its focus is Bellino Blins in the local dialect set at the top of the Vale Varaita in the Italian Alps above Cuneo. Bellino is a localised political unit, called a comune in Italian. My account Hence this account of Bellino reflects my own history and is coloured by other things happening in my life at the time.

There are two essential stages in the ethnographic process. First, in the field, we write down what we have seen and heard and felt in some form of journal. Since this usually happens at the end of a long day we are in effect writing down what we remember of the days events. Second, usually back at base, we write up those journal notes to challenge or to fit the framework of a particular theory or research question. This it is the harder part; it involves comparing and combining our findings with other peoples written up accounts.

Most often it is only the second stage exercise which is published; field notes may be archived and made available to selected future researchers, but they are seldom put on public view. Here, however, because my aim is to unpack the layers that make up ethnography I have included first stage field notes in this published account, neat, to provide background and context for the (second stage) analysis.

I use two devices to help the separate layers of ethnography leak into each other. One is that, wherever possible, the data are reported as they were given to me by individual informants; the reality of say cows is different for each of them and more faithfully represented by their separate cow stories (Non-English terms and colloquial phrases which appear in the text are translated in the Glossary at the back of the book.) The other device is more telling: the journal excerpts are selected from voluminous notebooks because they make most explicit reference to the presence and ethnographic significance of I would have been just another academic tourist from the lowlands, lacking crucial connective social tissue and quite without seriet i.e. without the gravity demanded of a proper woman.

The connectedness of the two layers is underlined by pairing the written up and not-written-up parts in alternating sequence. Each segment of field notes relates to events or themes of the written up chapter preceding it thus, for example, the chapter called Boundaries is followed by journal entries which relate, at least implicitly, to inclusions and exclusions; notes following the biographical case studies of Marie, Margherita, Caterina and Martin () are the fieldworkers not-written-up back story, describing occasions of my own and my childrens interaction with each of their households.

The Blins study is the only one of many field projects in which my family of procreation played a central and continuous part. It is also the only one to have languished unpublished for so long, even though the experience of it has stayed warm on the back burner of my mind over all the years: not only warm because glowing, but also warm like a splinter under the skin. When finally I came to writing it up, the ambiguity and its ambiguities extra sharp. How firm can the personal-professional boundary be when children insist on negotiating it? How uniplex are my relationships with women who feed and protect my children as they would their own? What context, whose context are we in when I react to my children spitting at each other? Or when the eldest is mocked at school for lack of Italian and someones father comes to weep with us when he hears about it?

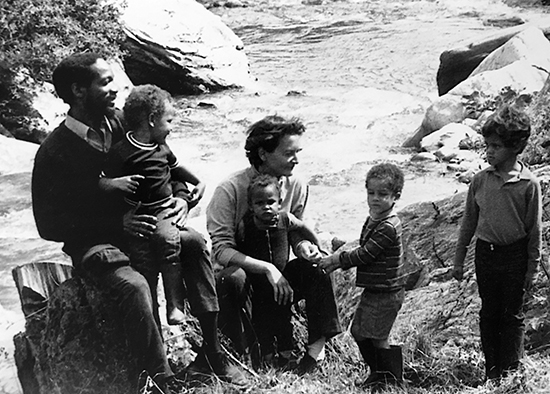

Figure 0.2 Our family complete. Photograph by the author.

It all happened a long time ago. Now all the contexts are different. The children have become adults, some have children of their own. I am older, inevitably. Less obviously, so is social anthropology: its emphasis and assumptions now are not what they were then, and the anthropological writer the writer as anthropologist has more right, as well as more obligation, to spell out the ambiguities of the research enterprise.

Contents

Contents Illustrations

Illustrations Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Introduction