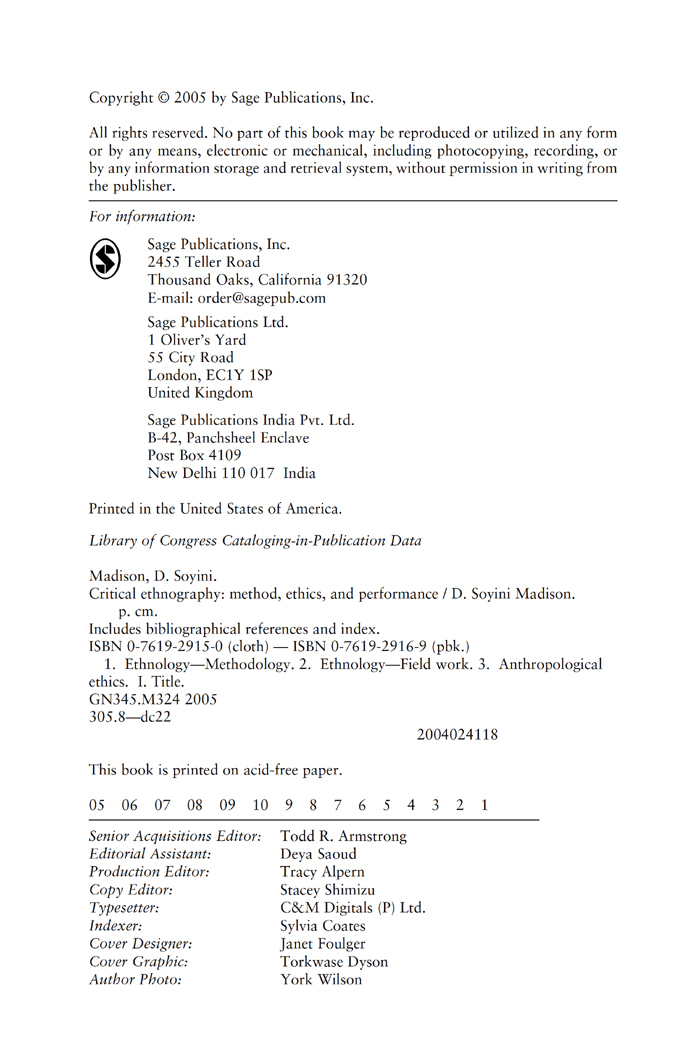

Critical Ethnography:

Method, Ethics, and Performance

D. Soyini Madison

Acknowledgments

[p. xi ]

Dwight Conquergood, my precious friend and teacher, for exemplifying an ethics of ethnography, championing social justice, and inspiring generations of dedicated scholars, teachers, and activists.

The Department of Communication Studies at the University of North Carolina, with a special thank-you to Julia T. Wood, Della Pollock, and Beverly W. Long for your brilliance and your extraordinary support over many years.

Robin G. Vander, whose friendship helped make this book possible and who also makes the phrase a friend in need is a friend indeed a reality and a saving grace. Your integrity and wisdom never cease to amaze me.

Wahneema Lubiano, Kara Keeling, Sue Estroff, and Genna Rae McNeil, for your friendship, intellectual generosity, and for your eloquence in naming the most pressing matters that beset the world.

Judith A. Hamera, E. Patrick Johnson, Tony Perucci, Joni L. Jones, Elyse Lamm Pineau, and Lisa Merrill, for consistently deepening my understanding of the politics and alchemy of performance.

Michael Eric Dyson and Marcia L. Dyson, for your compassion and genuine commitment to public knowledge.

A special group of graduate students, scholars, and rising ethnographers who have taught me in more profound ways than I have taught them: Robert Robb Romanowski, Bernadette Marie Calafell, Elizabeth Nelson, Hannah Blevins, Renee Alexander, Phaedra Pezzullo, Annissa Clarke, Rivka Eisner, Deborah Thomson, Mathew Spangler, Nathan Epley, Chris Chiron, Tes Thraves, Leah Totten, Eve Crevoshay, Brian Graves, Kate Willink, Mark Hayward, Rachel Hall, and, with deepest admiration and gratitude, to Lisa B. Y. Calvente, who has been my rock and my light.

Arlene Jackson, Akua McDaniel, Treva Cunningham, and Walter Cunningham, for your enduring encouragement, friendship, and support long before I knew the power of ethnography.

[p. xii ] Kwame William Obeng and Wisdom Mensah, for guiding me through the complexity of cultural codes and foreign territories.

Kingsley Kweku Acquah for helping me better understand the importance of world traveling and loving perception.

Abena Joan Brown, Val Gray Ward, and Useni Eugene Perkins, for over three decades of mentoring and enriching the lives of so many through committed leadership and community performance.

Staceyann Chin, for your excitement about this project, your respect for language, and your courage.

Lisa Aubrey, for your fearless commitment to truth and justice and for helping me to recognize the more complex translations required of politics on the ground.

Todd Armstrong and Deya Saoud, for your patience, understanding, and extraordinary skills in helping bring this book into being, especially during the last days of completion when my fieldwork hurried me away to the other side of the ocean.

Tracy Alpern and Stacey Shimizu, for your pleasant rapport despite cyberspace and for being so good at what you do.

Adwoa Sarkoa Ulzen and Amber D. Turner, for your excellent research assistance and careful attention to detail under pressure.

Elizabeth Bell, University of South Florida; Amy Kilgard, San Francisco State University; Angela Trethewey, Arizona State University; Nick Trujillo, California State University, Sacramento; Kristin B. Valentine, Arizona State University; and John T. Warren, Bowling Green State University, for reviewing the manuscript.

Reighne Madison Dyson, born July 19, 2003, for motivating me to care more and more each day about the future of this planet.

Mejai Kai Dyson, for your precise mind, your belief in the significance of fairness, and for demonstrating that good character is a precious thing.

Torkwase Madison Dyson, for your extraordinary artistic talent and for exemplifying what it means to teach and to live graciously from the heart and soul.

Yosiah Daniel Israel, for reminding me that love is the greatest possibility.

Chapter 1: Introduction to Critical Ethnography: Theory and Method

[p. 1 ]

Critical ethnography is conventional ethnography with a political purpose.

Jim Thomas, Doing Critical Ethnography (1993)

We should not choose between critical theory and ethnography. Instead, we see that researchers are cutting new paths to rein-scribing critique in ethnography.

George Noblit, Susana Y. Flores, & Enrique G. Murillo, Jr., Post Critical Ethnography: An Introduction (2004)

Last summer, while attending an annual, local documentary film festival in a small movie theatre with about 80 or more other interested people, I waited with great anticipation for one of the award-winning documentaries to begin. It had been highly recommended by a friend and the festival description was intriguing. From what I could gather, the subject of the film related to women's human rights in Ghana, West Africa. I was very excited about seeing it. I was hoping the film was inspired by the work of indigenous [p. 2 ] human rights activists in the developing world, particularly in Ghana, since it is a country for which I have deep affection. I lived there for almost three years conducting field research with local activists on human rights violations against women and girls.

As I waited anxiously for the documentary to start, I began to reflect back on my fieldwork and my days in Ghana working with and learning from Ghanaian human rights activists. I thought of the many sacrifices these people make in working for the victims of human rights abuses in their own country: by providing shelter and protection for them, by enlightening their countrymen and-women on the importance of human rights, and by their own political acumen in helping establish human rights policies. They are truly committed, openly condemning abusive cultural practices while simultaneously advocating for economic and social justice in the developing world. I witnessed so many of them being denigrated and condemned by members of their own communities; however, they forged ahead because of their belief in human dignity and self-determination.

The more I was exposed to the struggles of African men and women working in their own countries for peace, justice, and human rights, the more I realized how their work goes unrecognized by many of us in the West or global North. For many of us, the primary representations we see of developing countries, particularly Africa, are of tribal warfare, corruption, human rights abuses, and those desperately seeking asylum in the West. These representations do not tell the whole truth. The battle these local activists are fighting is one of immense proportions within their own communities that is made more difficult by the forces of global inequities. I remain inspired by the profound importance of their work. I welcomed this documentary as further credit to them.

The film began. A story was unfoldinga story being told by a young Ghanaian woman. My excitement grew. The camera focused on the young woman and shifted intermittently to particular sites in Ghana. As she told her story, she recounted the fear, helplessness, and desperation she felt when confronted by her father's demand that she undergo female circumcision (or what is variously referred to as female incision, female genital mutilation, or clitoridectomy). The portrayal was of a frightened young woman alone in a country where there was no refuge, no one to assist her, and no space of protection and safety. I was beginning to feel uncomfortable; there was something wrong with this story. The documentary came to an end, adapting a tone of hope and opportunity, as the young woman looked into the camera and poignantly expressed that she was finally safe: She had fled the dangers of Ghana. She is now in safe asylum in the United States of America.