PRACTICING

ETHNOGRAPHY

A Student Guide to Method and Methodology

Edited by

Lynda Mannik and Karen McGarry

Copyright University of Toronto Press 2017

Higher Education Division

www.utorontopress.com

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without prior written consent of the publisheror in the case of photocopying, a licence from Access Copyright (the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency) 32056 Wellesley Street West, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2S3is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Practicing ethnography : a student guide to method and methodology / edited by Lynda Mannik and Karen McGarry.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-4875-9313-1 (hardcover).ISBN 978-1-4875-9312-4 (softcover).

ISBN 978-1-4875-9315-5 (PDF).ISBN 978-1-4875-9314-8 (EPUB)

1. EthnologyMethodologyTextbooks. 2.Textbooks. I. Mannik, Lynda, 1957, editor II. McGarry, Karen Ann, 1972, editor

GN316.P73 2017 306.01 C2017-903412-X

C2017-903413-8

We welcome comments and suggestions regarding any aspect of our publicationsplease feel free to contact us at .

North America

5201 Dufferin Street

North York, Ontario, Canada, M3H 5T8

2250 Military Road

Tonawanda, New York, USA, 14150

ORDERS PHONE : 18005659523

ORDERS FAX : 18002219985

ORDERS E-MAIL :

UK, Ireland, and continental Europe

NBN International

Estover Road, Plymouth, PL6 7PY, Uk

ORDERS PHONE : 44 (0) 1752 202301

ORDERS FAX : 44 (0) 1752 202333

ORDERS E-MAIL :

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders; in the event of an error or omission, please notify the publisher.

This book is printed on paper containing 100% post-consumer fibre.

The University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund.

Printed in Canada.

Acknowledgements

Karen and I met while teaching a methods course in anthropology at York University. Our love of the discipline is what led us to finally write this book. We consider ourselves to be anthropologists who proudly work at home with a singular focus on culture in North America. A special thanks to all the undergraduate students who helped us better understand how to teach anthropological methods, and how to make this defining characteristic of the discipline accessible and valuable to others. It is our hope that this book will provide the tools for understanding others cultures and subcultures in a world that is so diverse. We have tailored this book to North American students projects, but we think that it might also be useful to anthropologists living and teaching in other places as well.

The relationships we developed with our contributors over the past few years are very important to us and to the integrity of this book. Not surprisingly, the group of North American anthropologists, Canadian and American, featured in this book are generous individuals who are devoted to cultural anthropology and its development as a discipline. They are all keenly aware that, as a discipline, cultural anthropology attempts to remain current while relying and focusing on century-old foundations in terms of theory and method. Their reflections on fieldwork experiences provide a holistic view of what cultural anthropologists do, think about, and strive to achieve. Each vignette was carefully crafted by our contributors with the aim of inspiring a new generation of cultural anthropologists, as well as others interested in qualitative methods. What they have decided to share are personal descriptions of what it is really like to be out in the field. Thank you!

We would also like to thank the team of production managers, editors, and others at the University of Toronto for their timely work and pleasant communication. In particular, we would like to thank Anne Brackenbury, who is an amazing editor. Without Annes help, this book would not have been as clear, concise, and comprehensive as it is. Thanks, Anne! Also, a special thanks to the reviewers who helped us hone the details of the book over the past few years. Although we will never know who you are, we hope you see your carefully crafted and constructive criticisms in the text.

Introduction

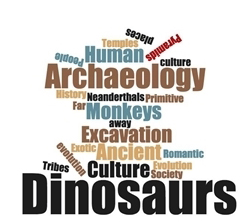

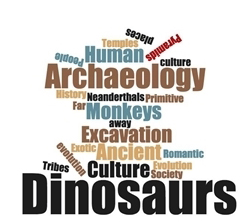

As an anthropology student, you have likely encountered many troubling, romanticized stereotypes about the discipline. Karen McGarry remembers once giving her incoming freshman students an exercise that asked them to write down the first five words that came to mind when they heard the term anthropology. She then made a word cloud that highlighted many of their common stereotypes about the discipline:

Figure 0.1: Word cloud generated on the first day of class by first-year anthropology students in response to the question, What do you think anthropology is? Karen McGarry, September 2015.

Many of you have undoubtedly challenged peoples misconceptions of anthropology as the study of the exotic or of dinosaurs. However, such essentialist public perceptions of the discipline are difficult to change in the face of sensationalist discoveries reported by National Geographic or Discovery Channel, which typically privilege archaeology over other disciplines. Similarly, the mainstream media tends to foreground visual representations of exotic peoples and locales, while sensationalist images of Otherness are frequently perpetuated in popular films, such as the Indiana Jones series.

Many of you have probably also had to justify your choice of anthropology as a major to your parents or other family members. In an environment where metrics and financial outcomes increasingly dictate notions of individual success, anthropology has been hailed as a poor choice of major for an undergraduate. In 2012, anthropology was positioned first in a ranked list of the ten worst college majors by Forbes magazine. Ranked on the basis of postgraduation incomes and unemployment rates, anthropology, it seems, is stereotyped as an interesting yet impractical major. Within the context of an increasingly neoliberal educational environment with corporatizing tendencies, universities are often expected to teach their consumers practical skills for long-term employment. Whether or not your professors support such trends, we are faced with an important question: Where does this leave anthropology? Long imagined (erroneously) as a strictly academic discipline that caters to the esoteric research interests of people with PhDs, anthropology, even sociocultural anthropology, can seem lacking in practical applicability. Do sociocultural anthropology and, particularly, tends to be promoted and favored within many government and corporate sectors as a form of solutions-oriented and problem-based research?