Tokelau: A Historical Ethnography is the outcome of over two decades of intensive and wide-ranging research in and about the three tiny Polynesian atolls of Tokelau. It is both a comparative ethnographic study of the islands and a narrative record of their past. The ethnographic study is set in the years around 1970. The combined stories of the atolls traditional, contact and colonial pasts are told through foreign documents which complement local narratives and records. Throughout, the differences and interrelationships between the three places are highlighted.

This is a comprehensive and substantial work, in which history informs ethnography and ethnography history. The volume is illustrated with maps and figures, ethnographic photographs by Marti Friedlander and the authors, and historical images from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. It is written to appeal to a wide readership, as well as to the anthropologist and historian.

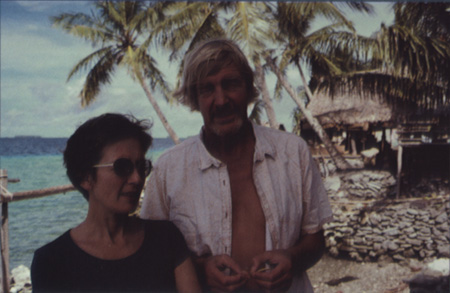

J UDITH H UNTSMAN is associate professor of social anthropology at the University of Auckland, and A NTONY H OOPER is engaged in independent research in Polynesia. Both are well known for their long-term research interest in Tokelau. Together they translated and edited Matagi Tokelau: History and Traditions of Tokelau.

TOKELAU

A Historical Ethnography

Judith Huntsman & Antony Hooper

First published 1996

This ebook edition 2013

AUCKLAND UNIVERSITY PRESS

University of Auckland

Private Bag 92019

Auckland 1142

www.press.auckland.ac.nz

Judith Huntsman & Antony Hooper 1996

This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without the prior permission of Auckland University Press.

eISBN 978 1 86940 664 6

Publication is assisted by

Royalties from this publication will be used in support of Pacific Island education.

J ACKET DESIGN Christine Hansen

J ACKET ILLUSTRATIONS

F RONT Photo by Marti Friedlander

B ACK (Bottom) Alfred T. Agate (1841) Cocoanut Grove and Temple: Fakaofo (Bowditch Island), oil on canvas, 10 14 inches. National Academy of Design, New York

(Top) Meeting house: photo by Marti Friedlander

A UTHOR PHOTO Neville Peat

CONTENTS

PREFACE

There are long and distinguished separate traditions of both ethnographic and historical research in Polynesia; none the less, anthropology and history in the region have always been closely allied with one another. In recent decades, for example, Polynesia has been the setting for a substantial academic tradition of island oriented narrative histories: Davidson (1967), Gilson (1970, 1980) and Newbury (1980) are a few of the better known. All were written by historians with some anthropological sophistication, using both European and indigenous historical texts to produce informed portraits of the indigenous polities as they were at the time of European contact, both as baselines for their narrative accounts, and to inform their interpretations of change.

Anthropologists have also made good use of historical sources for their own purposes, reconstructing aspects of culture and schemes of significance which are gone from the present and are now accessible in no other way. Valeris analysis of Hawaiian sacrifice (1985) shows perhaps better than any other recent work in the field the use of wholly historical sources for a characteristically anthropological projectthe depiction of an alien practice in terms of its motivating cultural logic. Again, Sahlinss recent studies (1985, 1990, 1992) of Hawaii and Fiji use historically documented myth, ritual and tradition not simply to extend the historical record but to explain it. Both these works have considerable analytic power, suggesting analogues right across the Polynesian region.

We have learned much from anthropologists and histories such as these, and have drawn freely from all of them in writing this bookeven though none of them directly addresses the central problem which has confronted us. Our concern here has been the ways in which an ethnography of the present might be conjoined with history. That, as we have found, is a special kind of enterprise, involving not only the connection of the past to the present, but the integration of two powerful but logically independent interpretive modes of dealing with the past.

Ethnography gives privileged access to a peoples contemporary representations of the past, to the ways in which knowledge about that past is constructed, passed on and invoked in everyday social life. This is the past as it appears in the present, which can be related to present-day structures of social and cultural significance. It matters little whether such representations are objectively true or not: myths, legends or fabulous genealogical structures can all be seen as part of the symbolic structures by which reality, both past and present, is perceived and understood. By comparison, narrative histories do not give such matters much attention. Historians commonly have less direct experience of such representations than ethnographers, are less concerned with their significances, and certainly less inclined to give them credence in their evaluations of data about the past as it really wasor can plausibly be made out to have been.

Ideally, one would think, these ethnographic and historical modes of interpretation might be placed side by side, evaluated and conjoined within a single narrative structure. There have, however, been few opportunities for this to be done in island Polynesia. Ethnographies are generally placed in relatively small, restricted local settings, where the significances of social action can be more readily grasped within a wide range of economic, political and ideological contexts. Such interpretations do not depend upon fictions of closed or insular systems, as some critics have maintained. They do, however, imply grounded, localised communities through which wider regional, national and even international systems of power and significance may be viewed; and that in practice has generally meant villages, districts and small islands, in which both discourse and social action are direct and largely face-to-face.

Other social scientists quite commonly regard such approaches as unnecessarily restrictive, if not quaint, and focus instead on settings of wider range. The narrative island oriented Pacific histories, for example, have been concerned primarily with the ways in which indigenous societies have been gathered into European protectorates, colonies and economic systems, and with their later transformations into independent or self-governing states. They have, certainly, connected the past with the present. But the present which is depicted is typically on a national rather than an ethnographic scale, with all traces of an ethnographic past elided by the broad sweep of history.

Ethnographies are not in any way incompatible with historical studies of this kind. They may at times provide illuminating perspectives on various aspects of national life, but the social and cultural realities which they depict are mainly of local scope and marginal to newer, more pressing national concerns.

Next page