This book made available by the Internet Archive.

P 373,1

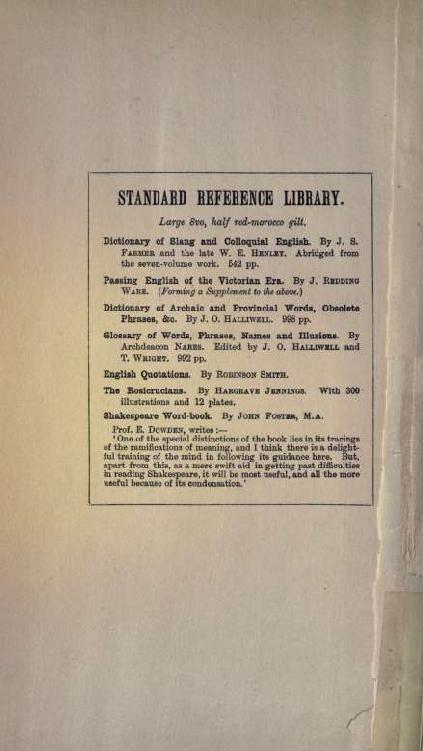

This Work forms a Companion Volume to

FARMER AND HENLEY'S

'DICTIONARY OF SLANG AND COLLOQUIAL ENGLISH'

IN THE SAME SERIES.

PREFACE i

HERE is a numerically weak collection of instances of 'Passing English'. It may be hoped that there are errors on every page, and also that no entry is ' quite too dull'. Thousands of words and phrases in existence in 1870 have drifted away, or changed their forms, or been absorbed, while as many have been added or are being added. 'Passing English' ripples from countless sources, forming a river of new language which has its tide and its ebb, while its current brings down new ideas and carries away those that have dribbled out of fashion. Not only is 'Passing English' general; it is local; often very seasonably local. Careless etymologists might hold that there are only four divisions of fugitive language in Londonwest, east, north and south. But the variations are countless. Holborn knows little of Petty Italia behind Hatton Garden, and both these ignore Clerkenwell, which is equally foreign to Islington proper; in the South, Lambeth generally ignores the New Cut, and both look upon Southwark as linguistically out of bounds; while in Central London, Clare Market (disappearing with the nineteenth century) had, if it no longer has, a distinct fashion in words from its great and partially surviving rival through the centuriesthe world of Seven Dials, which is in St Giles'sSt James's being practically in the next parish. In the East the confusion of languages is a world of ' variants'there must be half-a-dozen of Anglo-Yiddish alone all, however, outgrown from the Hebrew stem. ' Passing English' belongs to all the classes, from the peerage class who have always adopted an imperfection in speech or frequency of phrase associated with the court, to the court of the lowest costermonger, who gives the fashion to his immediate entourage. Much passing English becomes obscure almost immediately upon its appearancesuch as ' Whoa, Emma !' or ' How's your poor feet ?' the first from an inquest in a back street, the second from a question by Lord Palmerston addressed to the then Prince of Wales upon the

Preface

return of the latter from India. ' Everything is nice in my garden' came from Osborne. 'O.K.' for 'orl kerrect' (All Correct) was started by Vance, a comic singer, while in the East district, 'to Wainwright' a woman (i.e. to kill her) comes from the name of a murderer of that name. So boys in these later days have substituted 'He's a reglar Charlie' for 'He's a reglar Jack' meaning Jack Sheppard, while Charley is a loving diminutive of Charles Peace, a champion scoundrel of our generation. The Police Courts yield daily phrases to 'Passing English', while the life of the day sets its mark upon every hour. Between the autumn of 1899, and the middle of 1900, a Chadband became a Kruger, while a plucky, cheerful man was described as a 'B.P.' (Baden Powell). Li Hung Chang remained in London not a week, but he was called 'Lion Chang' before he had gone twice to bed in the Metropolis. Indeed, proper names are a great source of trouble in analysing Passing English. 'Dead as a door nail' is probablyas O'Donnel. The phrase comes from Ireland, where another fragmentTil smash you into Smithereens'means into Smither's ruinsthough no one seems to know who Smithers was. Again, a famous etymologist has assumed 'Right as a trivet' to refer to a kitchen-stove, whereas the 'trivet' is the last century pronunciation of Truefit, the supreme Bond Street wig-maker, whose wigs were perfecthence the phrase. Proper names are truly pitfalls in the study of colloquial language. What is a ' Bath Oliver,' a biscuit invented by a Dr Oliver of Bath; again there is the bun named after Sally Lunn, while the Scarborough Simnel is a cake accidentally discovered by baking two varying superposed cakes in one tin. In Scarborough, some natives now say the cake comes down from the pretender Simnel, who became cook or scullion to Henry VII. Turning in another direction, it may be suggested that most exclamations are survivals of Catholicism in England, such as 'Ad's Bud''God's Bud' (Christ); 'Cot's So''God's oath'; 'S'elp me greens'meaning groans; more blue (still heard in Devonshire) morbleu (probably from Bath and the Court of Charles II.)the 'blue death' or the 'blue-blood death ' the crucifixion. ' Please the pigs' is evidently pyx; while the dramatic 'sdeath is clearly 'His Death'; even the still common ' Bloody Hell 'is 'By our lady, hail', the lady being the Virgin. There are hundreds of these exclamations, many wholly local.

ri

Preface

Amongst authors perhaps no writer has given so many words to the language as Dickens from his first work, ' Pickwick', to almost his last, when he popularised Dr Bowdler; anglicization is, however, the chief agent in obscuring meanings, as, for instance, gooseberry fool is just gooseberry fouille, moved aboutof course through the sieve. Antithesis again has much to answer for. ' Dude' having noted itself, ' fade' was discovered as its opposite ; 'Mascotte' a luck-bringer having been brought to England, the clever ones very soon found an antithesis in Jonah, who, it will be recalled, was considered an unlucky neighbour. Be it repeatednot an hour passes without the discovery of a new word or phraseas the hours have always beenas the hours will always be. Nor is it too ambitious to suggest that passing language has something to do with the daily history of the nation. Be this all as it may behere is a phrase book offered to, it may be hoped, many readers, the chief hope of the author, in relation with this work, being that he may be found amusing, if neither erudite nor useful. Plaudite.

J. R. W.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

PASSING ENGLISH

A. D.

Academy Headache

A. D. (Ball-room programme). Drink, disguised, thus:

PROGRAMME OF DANCES.

1. Polka

2. Valse

3. Valse

4. Lanoers

5. Valse

6. Valse

7. Quadrille

8. Valse

Etc., etc.

Polly J. A. D. Miss F. Polly J. A. D.

Miss M. A. T. Polly J. A. D.

The ingeniousness of this arrangement is that young ladies see 'A. D.', and assume the youth engaged.

Abernethy (Peoples'}. A biscuit, so named after its inventor, Dr Abernethy (see Bath Oliver).

Abisselfa (Suffolk). Alone. From ' A by itself, A'; an old English way of stating the alphabet.

Abney Park (Hast London). About 1860. An abbreviation of Abney Park cemetery, a burial ground for a large proportion of those who die in the East End of London. Cemetery is a difficult word which the ignorant always avoid. Now used figuratively, e.g., 'Poor bloke, he's gone to Abney Park'meaning that he is dead.

We had a friendly lead in our court t'other night. Billy Johnson's kid snuffed it, and so all the coves about got up a ' friendly' to pay for the funeral to plant it decent in Abney. Cutting.

About and About (Soc., 1890 on). Mere chatter, the conversation of fools who talk for sheer talking's sake, e.g., 1 A more about and about man never suggested or prompted sudden murder.'

In an age of windy and pretentious gabblewhen the number of persons who

can, and will, chatter 'about and about the various arts is in quite unprecedented disproportion to the number of those who are content to study these various arts in patience, and, above all, in silence there was something eminently salutary in Millais' bluff contempt for the more presumptuous theories of the amateurs. D. T., 14th August 1896.

Next page