With each book there are always many people to whom I owe thanks. The usual suspects: Renee Paul, Aleta Boudreaux, Stephanie Chisholm, Susan Tanner, and Thomas Lakemanthe members of the Deep South Writers Salon. For fifteen years this group has read my first drafts, offering advice and constructive criticism. I owe them all a great deal.

My agent, Marian Young, is an indispensable part of the process. I trust her judgment and her knowledge and value her friendship.

A special thanks to Roscoe Sigler, who helped me with the technical details of the funeral business. When we were children, we played hide-and-seek on the grounds of his familys funeral home. Perhaps it was during this time that the seed for this novel was first planted.

And a big thanks to Kelley Ragland and the entire St. Martins gang. It is a pleasure to work with such a dynamic and enthusiastic group.

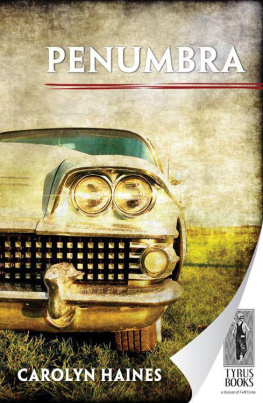

T he black Cadillac convertible churned down the dirt road, whipping whirls of dust behind it. The car, low-slung and fast, disappeared behind a stand of dark pines, leaving the landscape unexplainably barren. In a pasture beside the road an old mule grazed on grass burned dry by a merciless sun. From the shadow of a leaning barn came the low of a cow. The car sped by them, almost a vision, leaving only the settling dust and the taste of scorched dirt.

Behind the wheel, Marlena Bramlett pushed dark sunglasses higher on a perfect nose. A white scarf protected her hair, except for her bangs, which bobbed in hair-sprayed curls on her forehead. The red-and-white-striped shirt she wore hugged her breasts; darts emphasized her narrow waist. She drove as if her profile were the masthead on a ship.

Beside Marlena, standing in the middle of the seat, a six-year-old girl faced the wind. Brown pigtails, tipped with white bows, fluttered wildly behind the child.

I see him! Suzanna pointed up the road, her childish voice rising in excitement. Hes there. Hes waiting for us.

Sit down, Marlena told her daughter. You act like a heathen.

Will he have olives? The ones with the red things inside? Suzanna bounced up and down on the seat.

I dont know. Marlena passed the back of her hand over her forehead, smoothing the blond curls that, only half an hour before, had been pinned to lie just so.

Big Johnny lives on a red dirt road, and he tastes like chocolate, Suzanna said.

He gives you chocolate, Marlena corrected. And he thinks youre very smart. But thats our secret, remember? If you tell anyone, I mean anyone, you can never come with me again. The car fell into shadow as it entered a thick grove of pines. The road narrowed, and sand grabbed at the wheels.

I wont tell. Suzanna glanced at her mother, hurt. Id never tell on you.

Marlena slowed the car, finally stopping. She pulled her daughter to her side. I know you wont tell. Youre the one who loves me best. She kissed Suzannas cheek, then quickly brushed the fine dust from her daughters skin. If I didnt trust you, I wouldnt bring you. Now lets make sure we look good. She turned the rearview mirror so she could check her ruby lipstick.

Does Big Johnny really think Im smart? Suzanna twisted both pigtails in front of her chest. He says Im pretty, like you.

Does he really? Marlenas attention focused on the man half-hidden in the shadow of the car. She drove slowly abreast of the two-toned Chevy and stopped. The man sitting behind the wheel was tall, his black hair Bryllcremed back, white shirt unbuttoned at the collar. The ringless hand on the window was long and tanned, the nails neat. One finger thumped a rhythm.

Youre late, he said.

I couldnt get away. Lucas brought someone home for lunch.

Suzanna felt the tension between the two adults. Big Johnny was angry. He looked hot, inside and out. His olive skin was slick with heat, his black eyes burning. If Johnny acted ugly to her mother, Marlena would be upset for days.

I can count to a hundred, Suzanna said.

Im sorry were late, Marlena said. I came as quickly as I could.

We brought some iced tea, Suzanna said. Big Johnny loved iced tea. She held up the heavy gallon jar, lemons floating on top and ice rattling against the glass. Ive got glasses, too. And Mama dug worms for me. At last she had Big Johnnys attention.

You brought worms? His voice strained in an effort to be jolly. Worms for Susie-Belle-Ring-o-ling. Big Johnny got out of the car, his white teeth showing in a false smile. In his hand he carried a leather satchel. He went around to the passenger door and got in. Suzanna stood on the seat between the two adults, feeling suddenly trapped. Marlena put the car in gear and slowly drove away.

Ive missed you, Marlena said, her hands on the wheel and her gaze on the dirt road that wound ahead of them through the pine forests. Whereve you been?

Up to Mendenhall and Magee, Collins and Hattiesburg. I had to take Lews route when he came down with the fever. I would have called, but I cant. His voice was bitter. Your husband might answer the phone.

Marlena glanced at him, and Suzanna saw the pleading in her eyes. Im sorry. Thats just the way things are.

Im tired of the way things are. Big Johnny stared straight ahead, his voice low.

Suzanna leaned against the seat. She could feel the hot leather, now dust-coated. She didnt like it when her mother and Big Johnny were angry. She liked it when they laughed and teased each other, then her mothers blue eyes sparked and she was beautiful and alive. When they were angry, the fun left her mother and only the hard, cold shell of her body was there.

Mama said we could go fishing today, Suzanna said. Usually Big Johnny liked it when they went fishing.

I dont have time. Big Johnnys voice was punishing.

Please, Johnny. Marlena turned to him. I made an excuse to stay out for three hours. Its hard for me to find that much time away.

I feel like Im renting you. Watch the road, he snapped.

Dont say things like that.

Thats the reality. I feel cheap. Johnny pulled a cigarette from his pocket and lit it, the air from the moving car pushing the smoke behind them. His laugh was harsh. Isnt that the best? I feel cheap. I want more, Marlena.

There was a long silence that made Suzanna furious. She hated Big Johnny and she hated her father. They were stupid jackasses. Shed learned that word at school, and she was proud of it.

Finally, Marlena spoke. I dont have more to give right now, Johnny. If youd like, I can take you back to your car.

Suzanna watched the corner of her mothers mouth, the tiny tuck in the lips and flesh. Her chin was trembling and in a moment her mother would be crying. In a flash of fury, Suzanna turned on the man beside her. I hate you! She drew back her foot and kicked, catching the man in the ribs. He made a strange sound and leaned forward.

Suzanna! Marlena slammed on the brakes and put the car into a skid. The Cadillac turned sideways, wheels making the sound of tearing as they slewed through the sand.

Goddamn it! Johnny leaned across the seat and grabbed the wheel. He gave it a vicious jerk. The car swung heavy and fast, then righted itself and stopped in the center of the road. You could have killed us all! His arm was around Suzannas legs, holding her as she braced her hands against the top of the windshield. She would have been thrown out of the car if I hadnt caught her.