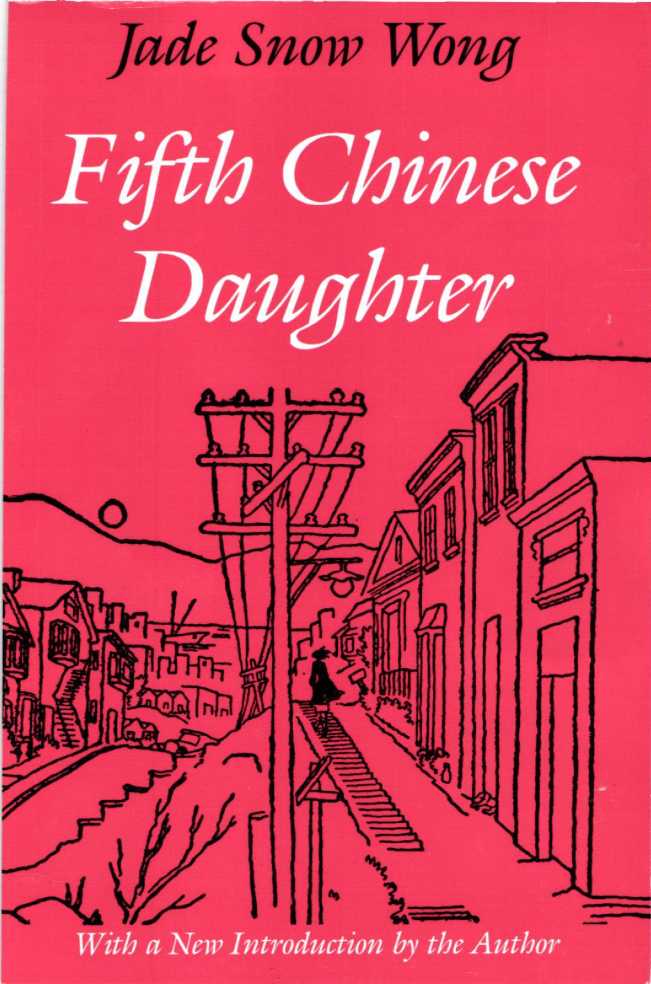

Fifth Chinese Daughter

Jade Snow Wong

With a New Introduction by the Author

Illustrations by Kathryn Uhl

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

Seattle and London

Copyright 1945, 1948, 1950 by jade Snow Wong

Copyright renewal 1978 by jade Snow Wong

Introduction to the 1989 Edition copyright 1989 by Jade Snow Wong

University of Washington paperback edition first published in 1989

Printed in the United States of America

15 14 13 12 11 10 14 13 12 II

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval

system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

University of Washington Press

PO Box 50096

Seattle, WA 98145-5096, U.S.A.

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wong, Jade Snow.

Fifth Chinese daughter / Jade Snow Wong; with a new Introduction by

the author; illustrations by Kathryn Uhl.

p. cm.

Reprint. Originally published: New York: Harper, 1950.

ISBN 978-0-295-96826-1 (pbk.)

1. Wong, Jade Snow. 2. Potters-California-Biography. I. Title.

NK4210.W55A2 1989 89-5302

738'.092'4-dc19 CIP

[B]

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and recycled from 10 percent post-consumer and at least 50 percent pre-consumer waste. It meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials,

ANSI Z39.48-1984.

To my mother and father

INTRODUCTION TO THE 1989 EDITION

A T THE AGE OF TWENTY-FOUR, I WAS AWARE THAT MY UPBRINGING by the nineteenth-century standards of Imperial China, which my parents deemed correct, was quite different from that enjoyed by twentieth-century Americans in San Francisco, where I had to find my identity and vocation. At a time when nothing had been published from a female Chinese American perspective, I wrote with the purpose of creating better understanding of the Chinese culture on the part of Americans. That creed has been my guiding theme through the many turns of my life work.

Although I felt it was important to record that period of my life, together with conflicting cultural expectations, I had no inkling of acceptance for my book. Who would be interested in the story of a poverty-stricken, undistinguished Chinese girl who had spent half of her life working and living, without romance, in a Chinatown basement? To my astonishment, readers and literary critics responded with great interest - and not just in America. Fifth Chinese Daughter was published in both England and Germany. In addition, the U.S. State Department published translations in the languages and dialects of Japan, Hong Kong, Malaya, Thailand, Burma, East India, and Pakistan. As a result, my book could create more than the hoped-for understanding of Chinese by Americans. Beyond America (even including Chinese), Fifth Chinese Daughter could offer insight into life in America.

The third-person-singular style in which I told my story was rooted in Chinese literary form (reflecting cultural disregard for the individual). Since that time, while I have succeeded in establishing my individuality on a local and international basis, I have nonetheless maintained my psychological detachment from my personal importance.

I have been rewarded beyond expectations. I recall a handsome young paratrooper in full military dress who appeared at my San Francisco studio on his way to Vietnam. He came to thank me for writing the book, which he had read in a Texas military base, for he would better understand the Asians where he was going. I also recall a long-distance call from a stranger in New York City. She had bought the book in San Francisco and read it aloud as her husband drove their way across the United States. She finished the reading by flashlight while he drove!

In 1953 the State Department sent me on a four-months grant to speak to a wide variety of audiences, from celebrated artists in Kyoto to restless Indians in Delhi, from students in ceramic classes in Manila to hard-working Chinese immigrants in Rangoon. I was sent because those Asian audiences who had read translations of Fifth Chinese Daughter did not believe a female born to poor Chinese immigrants could gain a toehold among prejudiced Americans. I was newly married then; my husband accompanied me at his own expense.

Having discovered kindred Asians halfway around the world, we established a travel agency just at the advent of the jet age. In 1956 my husband and I led a first tour of Americans to Japan. (Japanese freely acknowledge China as mother of their culture.) My early career as potter and enamelist put me on easy terms with those Japanese who were designated Living Human Treasures. For the next twelve years, we led a number of personally planned tours to Asian countries while, in between, I developed my ceramic arts and mothered two sons and two daughters. Husband and children knew that they held priority over my career. I have spent more time at my kitchen stove than at my kilns. It has been said that food, family, and endurance (in that order) characterize Chinese consciousness. Each of my children did homework in the kitchen while I coached and cooked, and each is now able to create delicious innovations at the wok.

In 1972 my husband and I succeeded in obtaining visas to the Peoples Republic of China - a month after Richard Nixons visit. (My book about that experience, No Chinese Stranger , was published by Harper & Row in 1974.) Together, we led a number of tours to China; since my husbands death in 1985, I have continued to do so once a year. This has enabled me to witness the remarkable changes there. Thus, I am carrying out my lifes creed in another way.

When I first visited China liberated by the Communists, seven years before general travel there, I was apprehensive about relating to those who would represent a way of life much different than that in the United States. Indeed, I found a cult of Mao worship, saw anti-American slogans in public places, and heard daily loudspeaker reminders that Americans were running dogs who must be defeated. But my husband and I were welcomed as descendants of heroic immigrants who had braved hardship to escape the harshness of an impoverished China in waning Imperial days. At formal banquets hosted by Communist officials, we were completely at home. Table courtesies were unchanged; our parents training of half a century ago is as appropriate in Beijing today as it has been in San Franciscos Chinatown. Everywhere that I have gone, in 1972 and now, I have had the unaccustomed comfort of being in a homogeneous Chinese populace (though, looking different, I am recognized as being from abroad).

I have learned from my travels that the lot of Chinese immigrants everywhere has been hard. The injustice of Americas past legal exclusion of the Chinese is well documented. My father was prevented from becoming a naturalized citizen until 1943, a year after I graduated from Mills College. Others of my race in Asia and South America have been denied citizenship, have lost property rights, have suffered persecution, and have been put on the ran - in Japan, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Burma, India, and, most recently, in Vietnam. Less than 150 years ago, Chinese were kidnapped from Macao for ranch labor in Peru and were physically branded as slaves. Depending on the period of history and the economic conditions prevailing in various coastal areas of Southern China, different communities of Chinese have emigrated to specific countries that could utilize their labor. Cantonese came to the United States, but from Chaozhou they went to Thailand, and from Fujian they went to the Philippines. Voluntarily, in ultimate risk-taking by venturing to lands and languages unknown, or involuntarily, as slaves, they labored to survive; to survive well, they had to be ingenious. And now, in 1989, some of their descendants, familiar with their parents or their own smarting as targets of prejudice or still finding restrictions in relocated lands, arc returning to invest in China in Special Economic Zones.