ALSO BY JAN WONG

Red China Blues: My Long March from Mao to Now

Lunch With

Copyright Jan Wong 1999

Paperback edition 2000

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior consent of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Reprography Collective is an infringement of the copyright law.

Doubleday Canada and colophon are trademarks.

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Wong, Jan

Jan Wongs China: reports from a not-so-foreign correspondent

eISBN: 978-0-385-67440-9

1. China Politics and government 1976 . 2. China Social conditions 1976 . 3. Wong, Jan. 1. Title.

DS779.2.W64 1999 951.059 C99-931393-2

Text design by Heidy Lawrance Associates

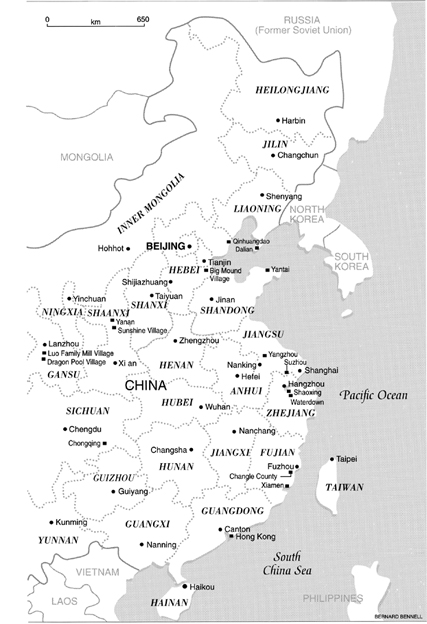

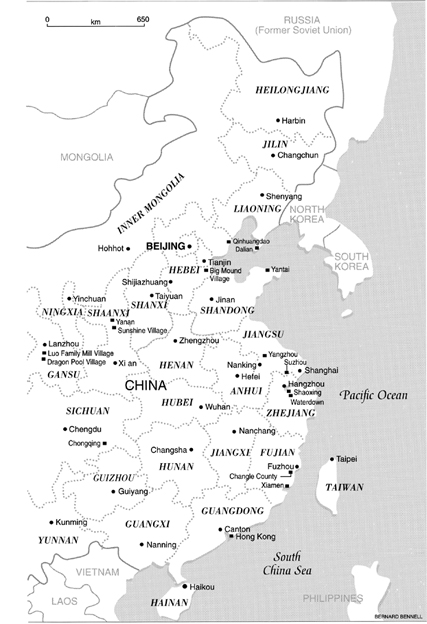

Map by Bernard Bennell

Published in Canada by

Doubleday Canada, a division of

Random House of Canada Limited

Visit Random House of Canada Limiteds website:

www.randomhouse.ca

The photographs on appear courtesy of the Globe and Mail and may not be reproduced without permission of the Globe and Mail.

v3.1

For Ben and Sam

Contents

Acknowledgments

John Pearce, editor-in-chief of Doubleday Canada, who first approached me to write Red China Blues, also inspired this book. Lesley Grant edited the manuscript with a sure touch and made invaluable suggestions. Michael Cohn was everything a literary agent should be.

For allowing me to draw upon my articles and photographs published in the Globe and Mail, Id like to thank Earle Gill, the papers Editorial Business Manager, William Thorsell, editor-in-chief, and Michael Doody, vice-president and general counsel of Thomson Corp. For my book leave, Id like to thank my Globe editors, Cathrin Bradbury and Sarah Murdoch. Johanna Boffa in the library provided emergency research. Paula Wilson in the photo library tracked down old negatives. Bernard Bennell drew the map. Stephen Strauss, as usual, maintained the flow of office gossip so I never felt lonely working at home.

Mel Mencher, my former professor at Columbias Graduate School of Journalism, explained exactly how I could and why I should make a final research trip to China in 1999 and still meet my tight deadline.

As a foreign correspondent in China from 1988 to 1994, my two closest friends were Catherine Sampson of The Times of London and Lena Sun of the Washington Post. Both were generous with their insight and information. They were also tremendous fun, even during the darkest days.

For help on this book, Id also like to thank other friends and colleagues in China, especially Ben Mok, Jaime FlorCruz, Susan Lawrence, Jim and Cathy McGregor, Jane Su, Joan Hinton and Sid Engst. Kathy Wilhelm, a former Beijing colleague in Hong Kong, sent me data promptly. Joanne Lee-Young in Hong Kong generously provided notes on her experiences.

I also thank my Chinese friends in China. You know who you are. Its best if the government doesnt.

In the United States, my matchmakers, Betty Zheng and Simon Hui, helped me, as always.

In Canada, my mother and my Aunt Ming read early chapters and encouraged me. When my obsolete printer sputtered, Cheuk Kwan helped me print out the second draft. In Toronto, Janet Brooks expertly read and corrected not one, but two, drafts.

My cousin-in-law, Colleen Parrish Yao, reeled off witty sub-titles at the drop of a hat, including the one we finally chose. She is assured of a job in publishing if she ever tires of managing a multi-billion-dollar pension fund.

In Toronto, Mercedita Iboro kept the household running smoothly, noting when we ran out of bleach and mayonnaise and remembering the boys dentist appointments. This book would not have been possible without her.

Nor would have it been possible without my husband, Norman. Fat Paycheck thought up the main title, helped me refresh old memories and hustled the boys off to karate lessons each weekend so I could work in peace.

And my boys. Every writer/mother should have angels like them. Ben, nine, and Sam, six, understood deadlines. And they were completely understanding one weekend when they had to eat hot dogs and chips and watch three videos in a row. I feared my maternal neglect would scar them for life until Ben one day said that he, too, wanted to be a writer.

A Note About Chinese Names

To help readers cope with odd-sounding Chinese names, I have often tagged on titles, such as Architect Zhang or Snakehead Yan or Migrant Worker Zhao. Occasionally, I have translated names, primarily as a memory aid, but also because knowing the meaning will help readers understand the culture and context. Parents, for instance, often named children according to the political movement of the day. My friend, Zhou Yue, whose name means Great Leap Zhou, was so called because she was born during the 1958 Great Leap Forward.

I have used pinyin, the official system of romanization in China. It is generally pronounced as it looks, with a few daunting exceptions. C is pronounced ts, q is pronounced ch, zh is pronounced j and x is pronounced hs. I dont expect anyone to remember that, so I often put a words pronunciation in brackets right after, for instance: guanxi (gwaan-see). With pinyin, some common English spellings have changed. Mao Tse-tung becomes Mao Zedong, Peking becomes Beijing and Chungking becomes Chongqing. In a few cases, I have kept the well-established English spellings: Chou En-lai, Canton and Nanking.

Family names precede personal names in Chinese, which is just another indication of the importance of the collective over the individual. With only about a hundred family names in common use and 1.3 billion people many people in this book have the same surnames. The reader can assume they are not related, unless otherwise stated.

In a very few cases, I have changed names to protect people. Reporters are supposed to let the reader know when. I have not. The reason is Id rather keep the Chinese authorities guessing.

The exchange rate has fluctuated over the years. I have tried to convert any yuan figures by the exchange that prevailed at the time. All dollars are U.S. dollars.

Prologue

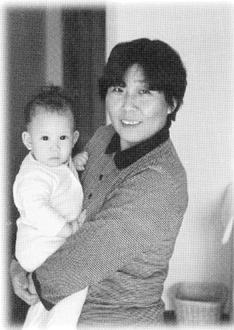

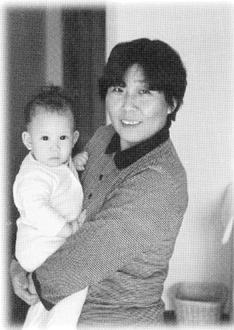

Nanny Ma and Ben in 1990.

Photo: Jan Wong

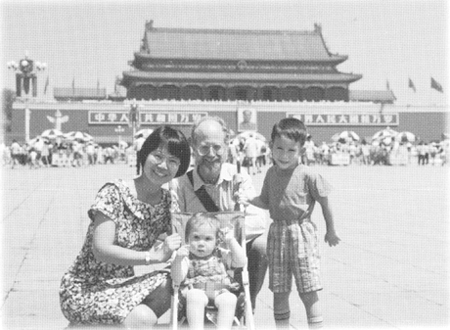

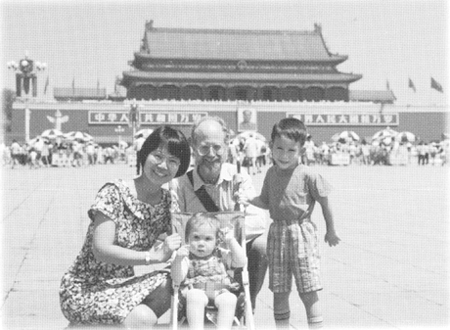

Author and family Norman Shulman, Ben and Sam (in carriage) in Tiananmen Square, 1994.