Contents

INTRODUCTION

Encountering China

CHRIS ELDER

The fiftieth anniversary of New Zealands establishing formal diplomatic relations with the Peoples Republic of China is unusual among diplomatic occasions. Most commonly, relationships between countries develop organically over time, but in this case the Joint Communiqu signed in New York on 22 December 1972 set the scene for a whole new beginning. It provided the springboard for a multifaceted relationship that has come to occupy a central place in New Zealands external dealings, and in the perceptions and the experiences of many individual New Zealanders.

This collection sets out to provide a patchwork built up from the memories, the experiences and the emotional responses of some of those who have been caught up in different aspects of the two countries interaction over the past 50 years. It offers 50 at 50 50 contributions centred on the period 1972 to 2022. The perspective it provides is a New Zealand one, leavened on occasion by the insights of those whose lives have spanned both countries. It makes no claim to be comprehensive, or definitive in any way. It stands simply as a record of how certain people have regarded certain aspects of the relationship at one time or another in the 50 years since the establishment of relations.

It would of course be simplistic to suggest that New Zealands links with China have sprung up only in the past 50 years. Modern research has revealed ancient DNA links back to North Asia among these islands first inhabitants. The earliest trade contacts date back more than 200 years not a long time in the annals of China, but pre-dating New Zealands existence as a nation. Mori were closely involved in those early contacts, just as iwi enterprises engaged with China today are flourishing. Appropriately, Encountering China takes as its starting point the response of the poet Hone Tuwhare to his opportunity to come face-to-face with China as part of a Mori workers delegation in 1973, which visited within a year of recognition.

Sojourners, and later settlers, came to New Zealand from China in numbers from the time of the 1860s gold rushes. In early years, they were subject to hostility and discrimination. In this collection, James Ng takes that period as his starting point in reflecting on his familys acclimatisation, while Esther Fung provides a coda to the transgressions of many years in her account of the process leading to a formal apology for past injustices.

It is true, nonetheless, that the agreement signed in 1972 paved the way for a substantial expansion of contacts between two countries which had spent the previous 23 years largely ignoring one anothers existence. It allowed the establishment of a range of official frameworks for interaction and co-operation, it provided a way forward for linkages between institutions and interest groups in the two countries, and it created the conditions that would promote familiarity and inform judgement going forward. If understanding between the two countries is still not all that it might be, New Zealands first ambassador to China grudgingly recorded at the end of his three-year term, it is at least better than it was.

The New Zealand government somewhat unconvincingly sheeted home its long-delayed decision to recognise China to the fact that China has now re-entered the mainstream of world affairs. That being the case, the official announcement noted, it was logical and sensible for New Zealand to recognise the Peoples Republic of China and enter into normal relations with it. Normal relations, the Joint Communiqu made plain, included establishing embassies in each others capitals. Cash-strapped New Zealand would just as soon have left the next step in abeyance for a few years, but was brought around by Chinas intimation that recognition without reciprocal representation would not, in its view, amount to recognition at all.

Inevitably, this compilation includes the recollections of some who, as diplomats, worked to support New Zealands political objectives in China. John McKinnon reviews that process from three different points in time, while Michael Powles struggles with the discovery that those supposedly better informed often are not. The relationship has been buttressed by a remarkable series of high-level visits in both directions, lending some credence to the perception that New Zealand has been seen as sufficiently small and non-threatening to provide a proving ground for senior Chinese leaders. That such visits have not been without their perils, particularly in the early days, is attested by the accounts of Chris Elder and Nick Bridge.

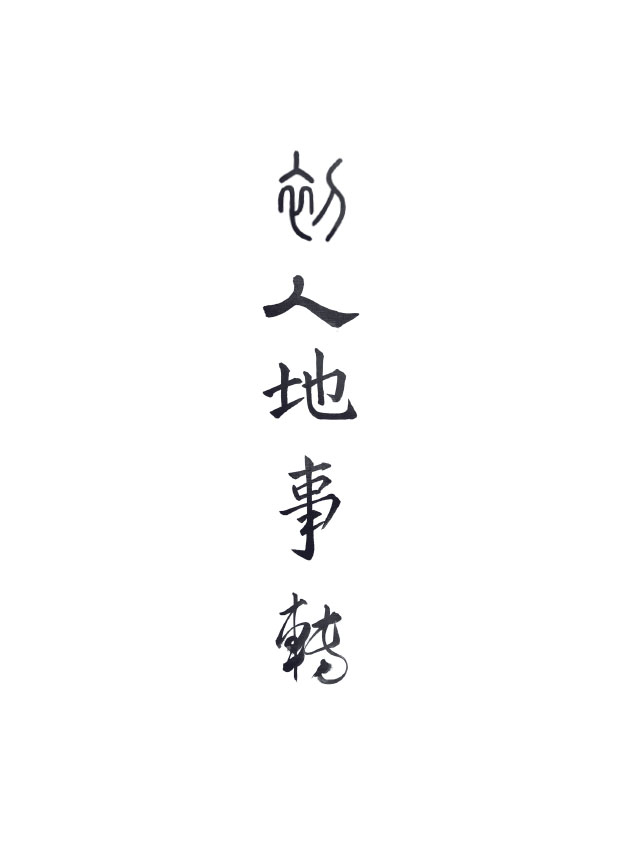

It is chastening to recall the level of ignorance in New Zealand about China at the time of recognition. One sight is worth a hundred descriptions (), according to a Chinese proverb, but not many New Zealanders had had the opportunity for even one sight. (One of the few who did, Philip Morrison, here describes a student trip in the lead-up to recognition.) People-to-people contact was largely in the hands of the small and left-leaning New Zealand China Friendship Society; party-to-party contact the preserve of Victor Wilcox and his associates in the Communist Party of New Zealand (CPNZ). Neither commanded a large hearing within New Zealand. Press reporting about China was filtered through a small coterie of Western journalists in Beijing, and a larger but not necessarily better-informed press corps in Hong Kong.

China, for its part, had not advanced much past the condition signalled in the 1602 geographical treatise Yueling guangyi , in which a world map showed an indeterminate mass roughly corresponding to New Zealands geographical location with the notation few people have been to this place in the south, and no one knows what things are there. In the early 1970s, the best authority on what things were there was to be found in the pages of the CPNZs Peoples Voice, which, as Chinese diplomats discovered when they arrived in Wellington, was not as authoritative as all that.

The half-century that has passed since the establishment of a formal relationship between China and New Zealand has seen major changes in both countries. China has become confident and outward-looking in its international dealings, to the point where it has come to vie with the United States for global influence. It has accepted Deng Xiaopings mantra that to grow rich is glorious, launching a programme of economic growth that has delivered a previously-unknown level of prosperity to its people and turned China into a vital engine of international economic growth. A number of the contributions reflect aspects of this process, not always without regret: I cannot help but feel, notes Phillip Mann, that something has been lost in the mad rush for economic prosperity.

Next page