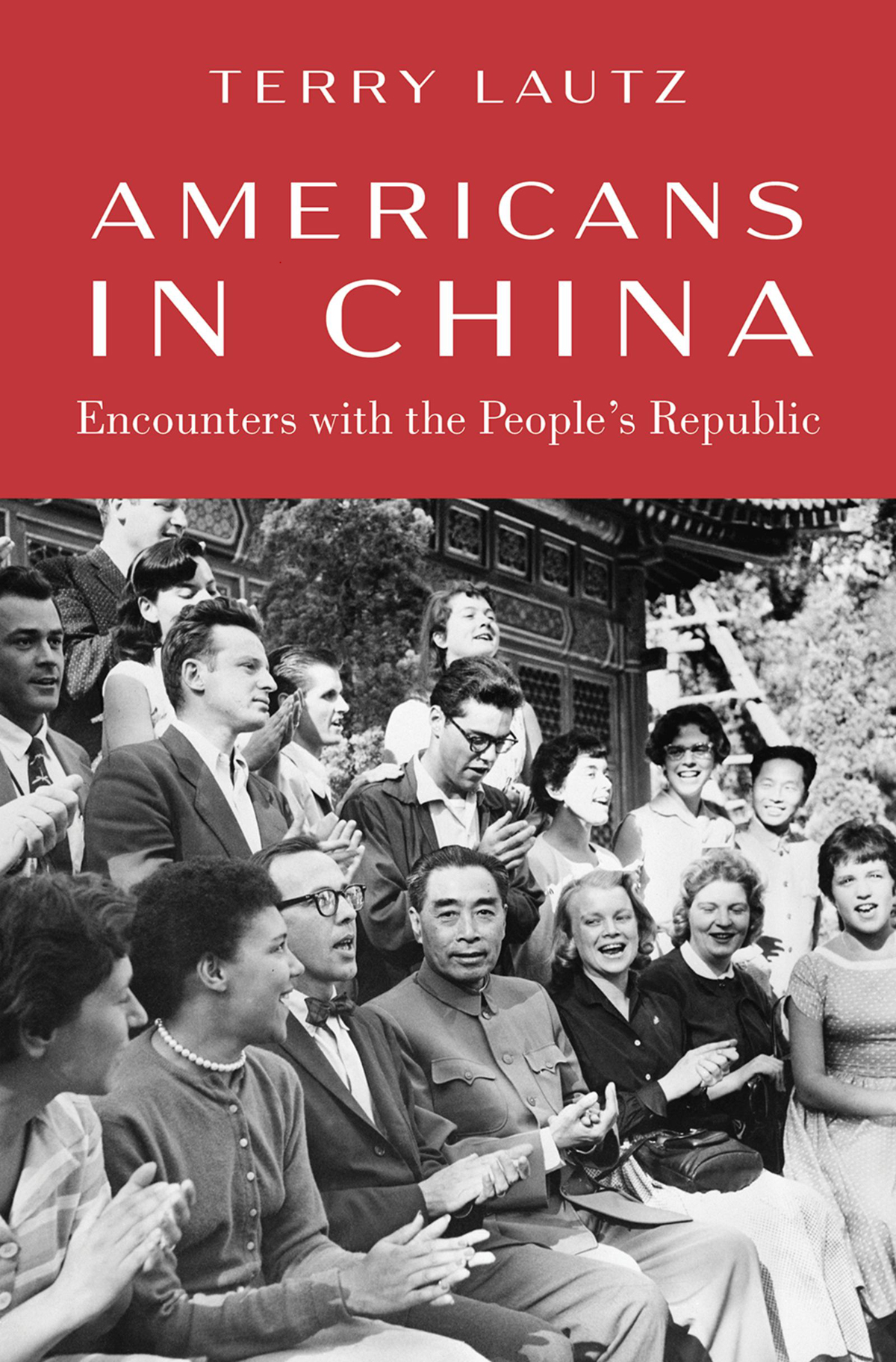

Americans in China

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780197512838

eISBN 9780192635358

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197512838.001.0001

In memory of Douglas P. Murray

Friend, mentor, and advocate for understanding

between the United States and China

Contents

In July 1960, I sailed across the Pacific Ocean from San Francisco to Taiwan with my parents and sister. After a calm and pleasant voyage, with a stop along the way in Japan, we disembarked at the port of Keelung on a hot, steamy day and drove for an hour to the capital city of Taipei where we would live for the next two years. I was nearly fourteen and it was my first encounter with anything Chinese.

The United States had diplomatic relations and a defense treaty with the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan, and my father, an Ordnance Corps Army officer, was assigned to the US Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG). Chiang Kai-shek, who had lost the civil war to the Communists a decade earlier, made speeches about recovering the mainland, but no one seemed to take his words seriously. While still under martial law, the island nation, some ninety miles off the Chinese mainland, was a poor, sleepy, peaceful backwater in those days.

That experience in Taiwan, where I attended Taipei American School, made me wonder about the Peoples Republic of China (PRC), a land shrouded in mystery that we could only see from a hillside on the Hong Kong side of its border. It made me curious enough to pursue Chinese studies as an undergraduate at Harvard, one of the few US schools offering that option in those days. Thats very interesting, my mother said when I announced my major, but what are you going to do with it? She was asking a serious question because there were so few China-related jobs. I simply trusted that something would work out.

Yet it was only after college, after serving in Vietnam with the US Army, that my curiosity became more purposeful. The people of South Vietnam feared communismmany of them had escaped from the Northbut their governments alliance with the United States undermined their claims to independence and nationalism. Reading Bernard Falls books about Ho Chi Minhs defeat of the French in 1954 made it painfully clear that the United States, perceived as another colonial power, was repeating the same fatal mistakes. The tragic result of our leaders ignorance of Vietnam, a war fought as a proxy against China, was a wake-up call for me. Understanding our fraught history in Asia had become more than an abstract intellectual exercise.

My timing was fortunate. During my graduate school days at Stanford, US-China relations began to improve with the advent of ping-pong diplomacy and President Nixons historic trip to the Peoples Republic. I returned to Taiwanthe mainland was still off-limitsfor Chinese language study and research on a Fulbright-Hays Scholarship. After receiving a PhD in history, I landed a job in New York with the Asia Societys China Council, a national public education program, led by Robert Oxnam, that connected with American scholars, journalists, businesspeople, and community leaders to provide balanced information on the PRC. Public interest was strong, but there was still a dearth of knowledge; we had yet, for instance, to realize the extent of devastation during the Cultural Revolution.

My first trip to mainland China, in December 1978, coincided with a major shift in the geopolitical landscape. I was escorting a small group of Americans, members of the National Committee on US-China Relations, on a three-week tour of several cities, starting in the north and ending in the south. On our final day, during a visit to the Huadong Commune on the outskirts of Guangzhou, I tuned in to Voice of America on my shortwave radio and listened to President Carter announcing that the PRC and the United States would establish full diplomatic relations.