Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2020 by Eugene Frazier Sr.

All rights reserved

First published 2020

E-book edition 2020

ISBN 978.1.4396.6971.6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019956018

Print Edition ISBN 978.1.4671.4520.6

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

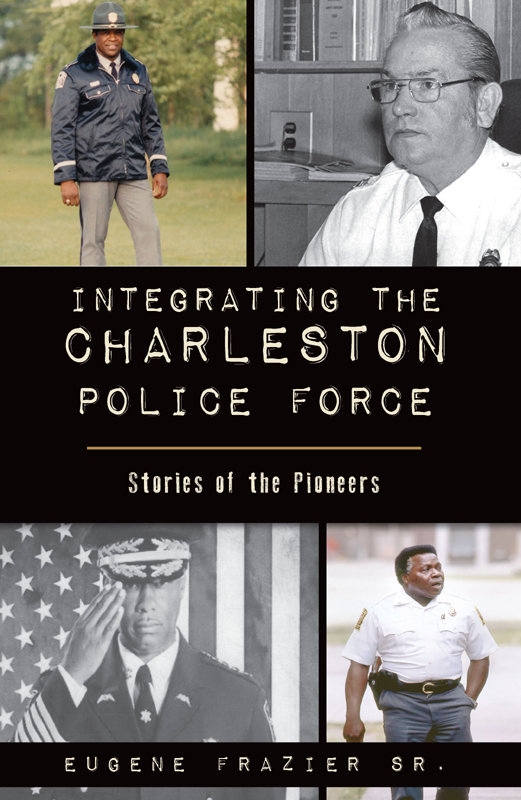

This book is a special tribute to all those pioneer African American men and women who served in law enforcement in Charleston County between the 1950s and the 1990s. Many were friends of mine. They suffered the frustration, humiliation and indignity of racism as they paved the way for generations to follow. Those who stuck with the job persevered and were able to retire. Those who were forced off the jobmy hat goes off to them. It is truly sad to say that some of the young African American police officers of today do not have a clue as to what their predecessors endured for them to have the privileges they enjoy. Once again, I salute the men and women who have gone home to a Greater Glory to receive their final reward that only God can give. May those brothers and sisters rest in peace.

This book is also dedicated to Chief Silas Welch, Chief Mikey Whatley, Chief John H. Ball, Chief Walter Gay, Assistant Deputy Chief D.M. Boggs and my friend Ronald Roddy Perry, a former partner in the homicide division of the Charleston County Police Department and later chief of the Mount Pleasant Police Department. These men, despite living and working in the segregated South, were able to put aside their white privilege that they knew existed to see the potential in other men and to treat those men with respect despite their race. I raise my hat to them. May they all rest in peace.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Charleston, South Carolina, sits on the East Coast along the Atlantic Ocean between North Carolina and Georgia. Charleston is known by its citizens as the Holy City. It is a place deeply rooted in the Bible belt and prides itself on its tradition of southern hospitality. It is a city known for its brotherly and sisterly love shown to thousands of visitors and tourists as they walk along the streets. It is known for its cheerful greetings of good morning and good evening and smiles and nods that are typical of Charlestonians. However, before the 1970s, African Americans were not afforded this friendly treatment and hospitality; whites treated them as second-class citizens.

African Americans were voting in the 1960s, but there were spelling or history questions that were put in place that made it difficult for them to vote. Many African Americans were not able to pass these exams. The Voting Rights Act passed in 1965, following a prolonged protest of the court system at the local and state levels. The pressure came from the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), its president J. Arthur Brown and other men, such as state senator Herbert U. Fielding, John Chisolm, John Cumming, Jack White, Reverend Cornelius Campbell of St. James Presbyterian Church on James Island and many others. Numerous meetings were held over the years with the late mayors William Morrison and Palmer Gaillard Jr. and other influential white leaders, concerning the plight of African Americans. In 1950, the City of Charleston, under Chief William F. Kelly, and because of pressure from the NAACP and the courts, hired the first group of African American police officers. However, second-class status remained the norm for these police officers and all African American citizens.

Senator Herbert U. Fielding. Courtesy of Frederick Fielding.

During the 1950s and 1960s, African American city police officers were not allowed to arrest white citizens. If a black officer apprehended a white citizen who was violating the law, he could only detain that person until a white officer took over. Black policemen were also not allowed to drive patrol cars. They were dropped off for their walking beats in the city limits by a white officer in a patrol car.

Many of these offensive policies began to change during the 1969 Medical College Hospital strike, when nurses and hospital workers walked off their jobs. The strike was no surprise to African Americans who were familiar with Charlestons history of oppression. This was the city where the Civil War began when the first shot was fired on Fort Sumter, and South Carolina was the first state to secede from the Union. The primary goal of white Charlestonians during the nineteenth century was to preserve the institution of slavery. A majority of white citizens were proud of this distinction, though many claimed that slavery was not the reason for the war. However, historians have proven them wrong.

Other improvements in the policies of the police departments of the city and county of Charleston took even longer to accomplish and demanded great fortitude by a number of individuals, both black and white. Ive been proud to be a part of some of those struggles and described them in my 2001 book From Segregation to Integration: The Making of a Black Policeman. But I want to give particular credit to many of the individuals who were part of the struggle to bring positive change to the area police departments. In the following pages, that is exactly what I will do.

Note: All of the victims names and addresses have been changed to protect them and their families, including the fictitious name of Tom Anderson, which was changed to protect his family.

CITY OF CHARLESTON POLICE DEPARTMENT

In 1950, Chief William F. Kelly hired the City of Charleston Police Departments first group of African American police officers. There were eight men in that esteemed group: Officers Bennie Taylor, Cambridge Jenkins, George H. Gathers, Monkue Henegan, Ernest Deveaux, Christopher B. Ward, Walter Burke and James L. Mikell.

I knew James L. Mikell for most of his career and worked closely with him. Mikell was about forty-four years old when I met him. He was about five-foot-seven, with a slender built and a medium brown complexion. He was in good physical shape. He graduated from Shaw University in North Carolina and was married to Jewel Mikell, who taught high school. They had one son. Mikell was soft spoken and had a professional demeanora no-nonsense individual. He was considered a father to many of the officers. He would listen and give his opinion and advice. During a number of interviews and conversations, he helped me understand the experiences of the citys first black officers.

Frazier, he said to me, when the first groups of us were hired in 1950, besides our police training, some of the first instructions we received from supervisors was that, as black policemen, we were not allowed to arrest white people.