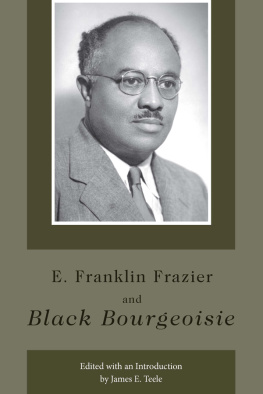

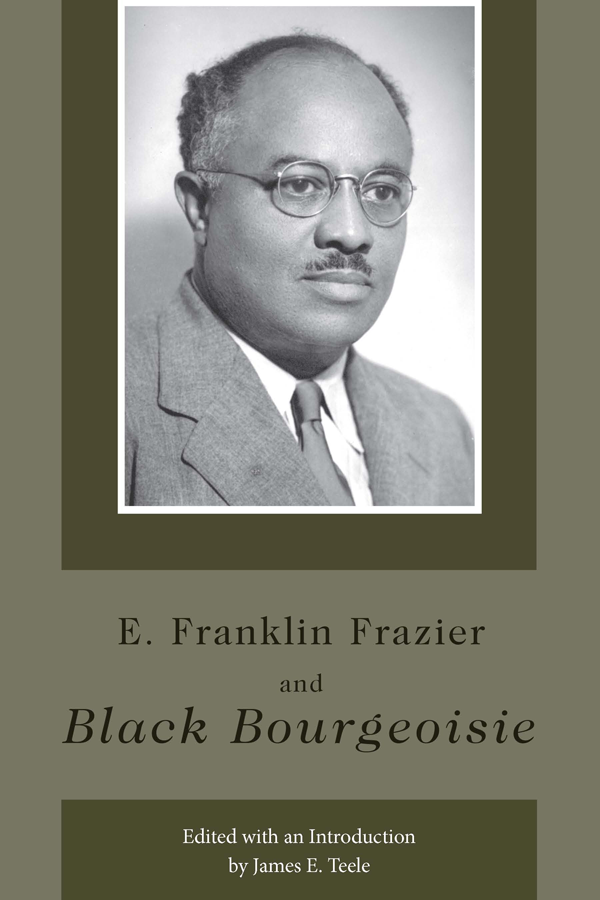

E. Franklin Frazier and Black Bourgeoisie

E. Franklin Frazier and Black bourgeoisie / edited with an introduction by James E. Teele.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8262-2150-6 (paperback : alk. paper)

1. Frazier, Edward Franklin, 18941962. Bourgeoisie noire. 2. African AmericansSocial conditionsTo 1964. 3. Middle classUnited States. 4. United StatesSocial conditions19601980. 5. United StatesRace relations. 6. Frazier, Edward Franklin, 18941962. 7. African American intellectualsBiography. 8. African American sociologistsBiography.

I. Teele, James E.

E185.86.F7283 E2 2002

305.896'073dc21

Previously copyrighted tables and charts appearing in the book are reprinted by permission of the National Urban League; the Russell Sage Foundation; and Black Enterprise Magazine (copyright 2002), New York, NY, all rights reserved.

The University of Missouri Press gratefully acknowledges support from Boston University in the publication of this book.

Acknowledgments

In a collaborative effort many people play important roles. I must begin by thanking Adelaide Cromwell, founding director of Afro-American studies at Boston University, for her inspiration, encouragement, and support in the effort to publish this work. The process started in the early 1990s when she, Wilson Moses (her successor as director), and I organized and presided over a one-day symposium that analyzed E. Franklin Fraziers Black Bourgeoisie. Five of the authors whose essays are included in this volumeAdelaide Cromwell, John Bracey, Martin Kilson, Wornie Reed, and Robert Hallproduced papers for that program. Later, Adelaide Cromwell suggested that I expand on our program and produce a book on Fraziers controversial work. Subsequently, the initial contributors were asked to revise their presentations for publication, and four additional scholarsMichael Winston, Hylan Lewis, Anthony Platt, and John Hope Franklinwere invited to contribute papers. Winston initially presented his paper at the meeting of the African Studies Association on November 3, 1990; Lewis was asked to prepare a paper on Fraziers early years at Howard University; Platt adapted his contribution from his book E. Franklin Frazier Reconsidered; Franklin graciously agreed to share some of his experiences as Fraziers student, colleague, and friend. First and foremost, I am grateful to the contributors; their creativity, dedication, and response to the editors and reviewers suggestions made this volume possible.

I wish to express my deep appreciation to both the Association of Black Sociologists and the American Sociological Association for inviting me to organize and preside over a special panel on Frazier at the ASA meeting in August 2000. This panel brought together Andrew Billingsley, Platt, Cheryl Gilkes, Clovis Semmes, and Stanford Lyman, and their discussion ranged widely over Fraziers signal contributions to sociology, social work, and the larger society. Panel members, with their outstanding analyses of Frazier, helped to sharpen my understanding of Frazier, and I am convinced that their views have contributed significantly to my editorial performance.

I am also indebted to Boston University, which served as the setting for our initial symposium. Dennis Berkey, the Provost of Boston University, provided special funds to me that greatly aided in all the projects indispensable tasksmanuscript preparation, travel to several conferences for the purpose of meeting with prospective contributors, and editorial assistance.

Library staff at Boston University, Virginia Union University, and Howard University and in the town of Ipswich, Massachusetts, were quite helpful in providing requested assistance at various stages in this project.

My wife, Ann Skendall Teele, was, as always, highly supportive of my work. However, in this case, I am especially grateful to her for encouraging me to take on the Frazier project. Edgar F. Borgatta, of the University of Washington, also encouraged me to undertake this task. Borgatta, a graduate student at New York University when Frazier was a visiting scholar there, spoke admiringly of Fraziers performance and popularity.

I am especially appreciative, too, of all the help I received in manuscript preparation from the sociology department staff at Boston University: Kimberly Warren, Maddie Goodwin, Katie McNamara, and Joshua Kaplan. I also received invaluable editorial assistance from Leslie Tebbe, a recent Boston University graduate and one of my former students.

Finally, I cannot say enough about the fine editorial assistance I received from the staff at the University of Missouri Press. I am especially grateful to Beverly Jarrett, the director and editor-in-chief, for her constant support and encouragement and to Jane Lago, managing editor, and Sara Davis, both for their knowledge and their readiness to help me through the editing process.

Introduction

JAMES E. TEELE

For this essay collection, a group of distinguished scholars set out to reexamine and clarify, for themselves at least, some of the work of E. Franklin Frazier, a highly acclaimed sociologist. Despite E. Franklin Fraziers status in American sociology there has been surprisingly little study of his work. While scholars have frequently referred to his work on the black family and he has been the subject of at least four doctoral dissertations, there has been only one book about his life and surprisingly little study of his work. In the biography, Anthony Platt observes that assessments of Frazier have generally denied the complexities, the uniqueness, and the consistency of the themes that preoccupied him.

There is much to be gained from a close examination of Frazier. In this volume, essays by a number of distinguished scholars focus on the complexities of Black Bourgeoisie, Fraziers most controversial and perhaps least understood work, rather than attempting to analyze his entire body of work. This concentration is relevant to the growing concerns about problems in our cities, about the limitations and advantages of affirmative action, about racism, and about the need for community. It also reflects a renewed interest in Frazier demonstrated by the publication of new editions of his work, the naming of a Howard University research center in his honor, and the aforementioned American Sociological Association/Association of Black Sociologists joint session. Increasingly, Frazier is being studied by students in history, sociology, political science, psychology, and African American studies.

This diverse audience recognizes that all of these disciplines were used by Frazier in his work on race relations, the family, and blackcommunity life and that he invariably addressed important questions in his work, thus leading him to assume the different roles of activist and theorist, detached scholar, and radical advocate of social change at various times in his life. Therefore, this volume should be of interest to policymakers and activists as well as scholars.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.