Thank you so much to my agent, Liz Nealon, for enthusiastically, tenaciously submitting my manuscript to publishers. And to her associate, Mona Kanin, whose editorial work on preparing my manuscript for submission was rigorous and oh so helpful, as was the copyediting work of Bob Byrne. To Susan Kilby, managing editor of development at McFarland, and to Dr Person, assistant editor, for guiding me through the publication process. Thanks, in fact, to everyone at McFarland for so generously embracing and preparing my memoir for publication.

I would also certainly like to thank all my family and friends who read and commented on various chapters of the memoir as I developed it over the years, writing between, around, and through my writing for theater, television, and various magazines and literary journals.

Certain artist residencies have also been of particular importance. Thank you McDowell and Yaddo and Millay. Thank you Bogliasco. And a truly special thank you to the Blue Mountain Center, for it was there, two decades ago, that I wrote the very first draft of the first chapter, Drive. And it was also at BMC in the summer of 2021 that I put the finishing touches on the manuscript as a whole. BMC has truly enveloped and embraced both me and my work.

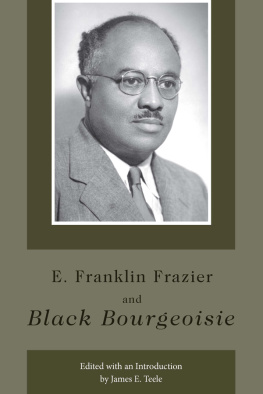

A special thanks, of course, is due to my wonderful parents, Bernard Ford Frazier and Martha Davis Frazier, now deceased. I am so grateful that each had the opportunity to read at least an early draft of the memoir. And thanks to my brother, Dennis G. Frazier, Sr., and my sister, Sheila F. Lonesome, for their continued love and advice. A special thanks to my ex-wife and still good friend, Leena Kuivanen. And most of all, much thanks and love to my beautiful daughters, Eliisa Martha Frazier and Katja Helena Frazier, and to my four beautiful grandchildren, Kingston, Wesley, Anton, and Ruby, who forever inspire me and bring such joy to my life.

Prologue

Turn around, Kermit.

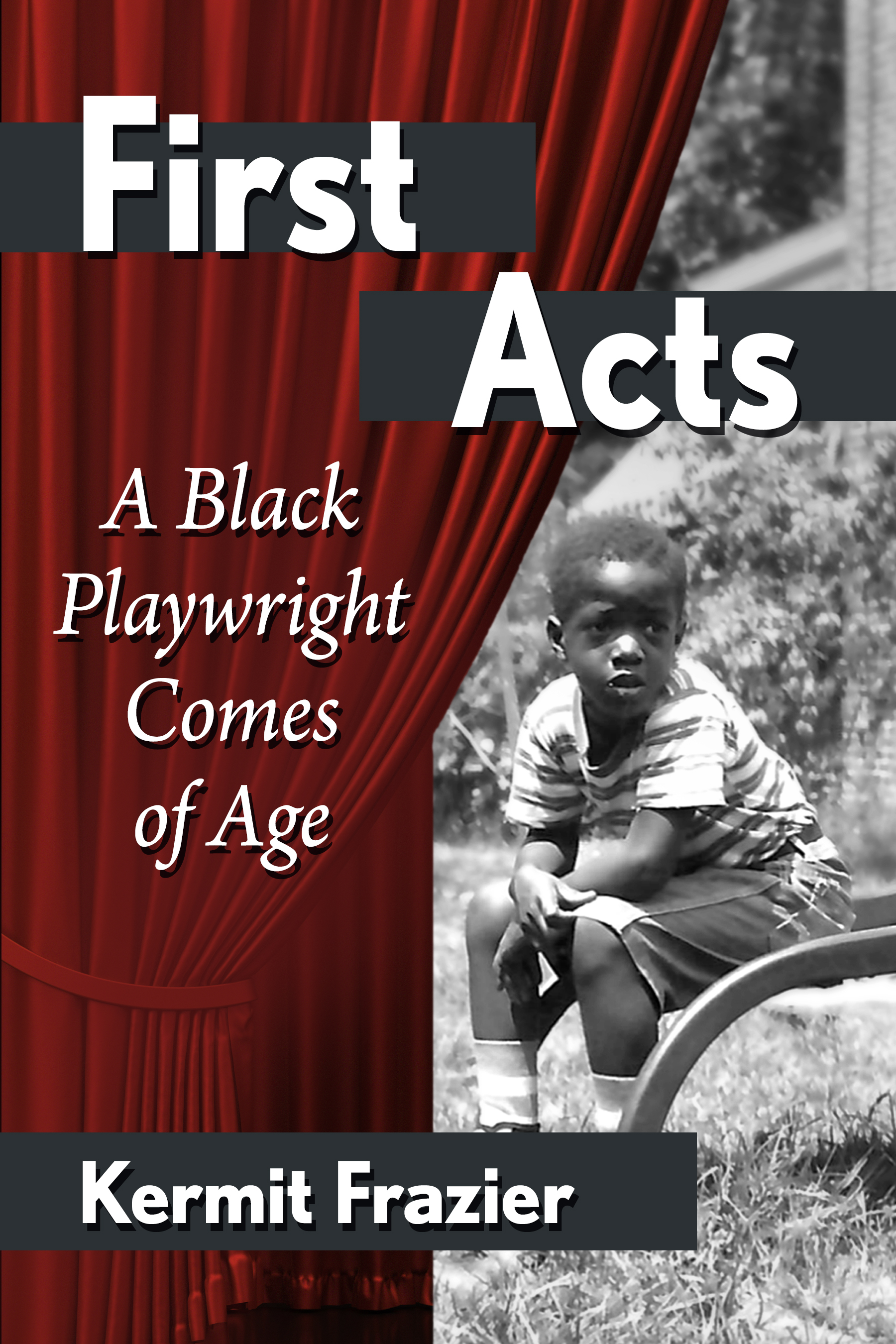

And so I had. Me looking like a waif in that sepia photo, despite my being surrounded by three generations of one side of my family: my paternal great-grandmother, my paternal grandfather, an aunt and an uncle, and my dad. All of them smiling easily, almost cockily. The keen and quiet confidence of a middle-class Black family in Washington, DC. Or more precisely Anacostia, a section of Southeast DC.

But in that fascinating photo my relatives smiles are essentially atmospheric, a strongly ambient background glow. The foreground is inadvertently reserved for me, the shy, rather reticent subject of the photograph.

Author at Thanksgiving table in 1954 with (seated from left) Grandpa Frazier and Great Grandma Ford and standing (from left) Uncle Leo, Aunt Evelyn, and Bernard, authors father.

Turn around, Kermit, someone must have said. Probably my mom, a camera forever at her disposal, strapped both to her sensibilities and her immutable need to preserve.

Kermit. A name my father had given me because he knew someone by that name and liked it.

Turn around, Kermit.

And I had dutifully obeyed, turned my head as I sat sternly in my chair, hands together under the table between my legs, a glass of milk waiting on the table near my still-empty platea glass etched with a cute little white boy, hobo stick in hand, marching insouciant, probably down some country road. My glass.

I look pliant and nave, with sweet lips and a kind of gaze in my eyes that suggests a combination of wonder, need, and incipient fear. A look, however, thats shaded and shadowed by a curious kind of grownup gravity on my brow.

Its the fall of 1954. And judging from the fat, luscious turkey that graces the festive-looking dining room table, were posing at Thanksgiving. Our house. Although I have no idea where my younger brother Dennis and younger sister Sheila are. Perhaps at the other end of the table. In any event, theyre missing in the photo.

Its a house that my parents rent from my fathers father. George Frazier first lived there with his family before moving down the street to still another house he had built. Grandpa, head cocked and looking away from the camera, is seated to my immediate left. And then theres my dad, standing behind his grandmother, leaning with his left elbow on an old, low-rise wooden China cabinet. Cool, calm, collected, and less in direct light than any of us. He appears even more handsome, more provocative and hip, than he normally doeslooking as though he were an on-the-road jazz musician deigning to visit his family over the holidays, the bold bebop of Charlie Parker ever looping in his head.

As for eight-year-old me? Well, I wonder whats looping through my head. I wonder why I appear so lonely, so alone, in this fine, familial, before-gracing-the-table scene. I long to melt into the picture, to be that Negro kid at that precise moment once again. But in critical ways all I can do is lookstare and stare into my eyes peering back at the camera and beyond.

How many such pictures generate as much longing as they do details? How many such photographs do we have of ourselves growing up: frozen in time or ever looping through our minds; pressed into albums or fixed in our memories yet ever suing for realignment; faded by exposure, or hidden behind others, or as crystal clear as the light of some new day, some new discovery? How many ways do we have of seeing our past selves, how many aspects of perception? What, in fact, is the right, or at least the best, way to piece the puzzle of self?

Drive

I

My father drove me. He drove me in our green, squat-looking 1954 Chevrolet, a rounded bug of a Bel Air before that model sprouted wings as though it were meant to fly. He could drive me because he was working the four-to-twelve shift at the Navy Yard so that he could get my brother, sister, and me breakfast and off to school, since my mother was a full-time student and busy with her own crucial work. He was a quiet, conscientious, steadfast father who was perhaps the least formally educated among his brother, sister, and cousins, having dropped out of Howard University after a year and a half, joined the Navy, and become a machinist, working for the federal government his whole life. Yet in many ways he was perhaps one of the brightest, the most practical and spiritual, and in some sense the clearest thinker. He drove me because he also drove a taxicab part-time and knew the streets of DC like the back of his hand. Drove me down Shannon Place from our house to Talbert Street, then up Nichols Avenue past his old elementary school and our Baptist church, over the bridge past my old elementary school, up, up the hill past the hospital into an essentially white neighborhood that had a movie theater we couldnt go to until recently. Drove me along Alabama Avenue for a couple of blocks and then down Wheeler Road into Oxon Run and right on Mississippi Avenue to my new school.