Table of Contents

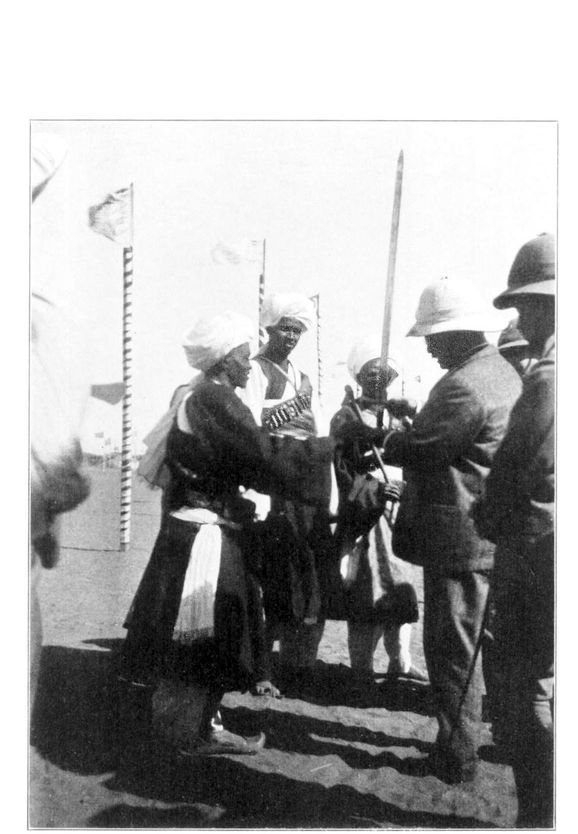

Arab sheikhs who had ridden in, camel-back, from the desert to pay their respects

To

The Mistress of Sagamore

INTRODUCTION

I am fond of politics, but fonder still

of a little big-game hunting.

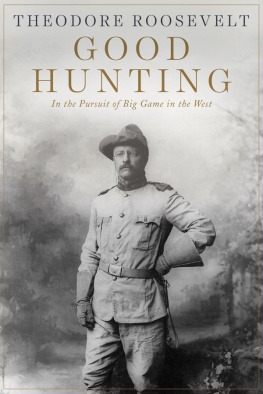

Theodore Roosevelt

IN April 1909 young Kermit Roosevelt left his studies at Harvard University and set out with his father, Theodore Roosevelt, the twenty-sixth president of the United States, on a year-long adventure into the wilds of eastern Africa. His father, now fifty and blinded in his left eye by a boxing injury, was relying both on Kermits youth to compensate for his own lost physical ability and on his ability to write and work with the camera to ensure that the right image of their regal adventure made it to press. Preparations for what was to be the largest and most ambitious hunting expedition ever in Kenya began in his childhood home, the White House, a year before, where a practice firing range was set up to assist in honing their marksmanship skills. They enlisted the advice of the well-traveled Frederick Selous and Edward North Buxton and the expertise of Kenyas two most famous hunters, R. J. Cuninghame and William Judd, and engaged Nairobis premier safari outfitter. The expedition departed amidst great fanfare aboard the German steamship Hamburg from New York harbor and met up with the Admiral from Naples for the journey across the Red Sea and Indian Ocean to Mombasa. While an already impressive undertaking, this was only the beginning of the Roosevelts travels. Five years later the father-son team set out again to explore the Amazon jungles of Brazil and fifteen years later Kermit embarked on another hunting trip to China with his brother in search of great pandas. Theirs was a time of exploration, a time immortalized by his personal friend, Rudyard Kipling, whose far-flung tales of adventures excited the imaginations of the Roosevelt children in their childhood and inspired Kermit in particular to set out to explore some of the worlds most remote territories as a kind of rough rider in his own rite. Like so many big-game hunters and explorers before him, Kermit turned to writing, recounting some of these almost incredible real-life adventures in this eloquent and unvarnished gem, The Happy Hunting-Grounds.

Kermit Roosevelt, was born in Oyster Bay, Long Island, New York in 1889, the second child of five children in the Roosevelt family. As his siblings had, he attended public school and later transferred to Groton, the prestigious Connecticut prep school, where his father had also been a student. Although gone from university for a year on safari, he still managed to complete an accelerated degree at Harvard, after which he worked as a manager in the National City Bank in Buenos Aires and took off again on expedition to the Amazon. At the beginning of WWI, he married the daughter of an American ambassador to Spain in Madrid and enlisted as a captain in the British armed forces in Mesopotamia. His military experiences fighting with the British can be found in his War in the Garden of Eden (1919). Having contracted malaria, he was then transferred to the United States army in France until the end of the war, after which he established and ran the lucrative Roosevelt Steamship Lines in the 1920s. It was then in his late twenties and thirties that he began documenting his wildlife adventures in The Happy Hunting-Grounds (1920). The volume opens with his account of the Mombasa hunting expedition in equatorial Africa followed by the tales of later treks taken after his return to his studies, his trips to the American Southwest to hunt mountain sheep, explorations into the Canadian and South Dakotan outback, the Mexican desert, and with his father, almost a decade after Conrads Heart of Darkness (1902), into the heart of the Amazon in the Brazilian wilderness to trace the uncharted River of Doubt (Rio Roosevelt), a harrowing trip which almost cost his fathers life. The narratives, while providing readers with a privileged look into the private life of Teddy Roosevelt as both father and outdoorsman, are also fascinating historical accounts of the sport of big-game hunting and count among some of the first authentic and unapologetic reactions of civilized Westerners to wilderness and other cultures at the turn of the century. One can imagine from the wealth of priceless original photos and drawings by Kermit, who was also the photographer and press liaison on many of these expeditions, that his travel experiences must have seemed to him like childhood adventure stories come to life. After completing East of the Sun, West of the Moon (1926), his account of collecting fauna in Eastern Turkistan, and Trailing the Great Panda (1929), which appeared after searching for pandas with his brother in the hinterlands of Tibet, Kermit ran into hard times in the Depression, became an alcoholic, and resigned before being recomissioned under Churchill and serving the British army in Norway and Egypt. Kermits wife arranged for him to be stationed in the desolate U.S. army post at Fort Richardson, Alaska, where he assisted in bombing raids against the Japanese in the Aleutian Islands in WWII. But his bouts of depression never left him, and he committed suicide in Alaska in 1943, where he is buried.

Kermits early literary experiences, transmitted as they were through the powerful figure of his father, indeed had a lasting influence on his imagination and the direction his life would take. An accomplished writer of adventure tales himself, Teddy Roosevelt initiated all of his sons at an early age into a pedagogy of both sports and literature. He proudly acknowledges the result of Kermits upbringing in a letter he wrote to Ethel on their African journey: It is rare for a boy with his refined tastes and his genuine appreciation of literature and of so much else to be also an exceptionally bold and hardy sportsman. For him, adventure literature, whether written by their family friend Rudyard Kipling, Henry Thoreau, Jack London, or published in sportsmens magazines, as the actual adventures themselves, was an opportunity for boys to learn about nature, but also about becoming men. Roosevelt rejected romantic depictions of blissful nature as he did Mark Twains protests against hunting, insisting instead on natures inherent violence and cruelty, which he felt justified mans vigorous uses of power. The late Victorian era was after all the age of Darwinism, which featured an aggressive confidence in the triumph of the fit. For the nineteenth-century American male, on display in public sports like boxing and big-game hunting, fitness implied both physical and moral superiority and was an essential ingredient of, indeed equated with manliness, an idea of exceptional importance to contemporary males and in particular to the identity of Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders, (his well-known cavalry unit of a few hundred Dakota and other cowboys, Ivy league football players, New York City cops, and about fifteen Native Americans). Despite recent evolutionary theory and conservationist policy, for the Roosevelts nature was still mans proving ground and the sport of hunting created the space for that contest to be dramatized.

As a result, hunting narratives were tremendously popular at the time with the male reading public of all ages, especially with Kermits father, who was an avid collector, particularly of those books dealing with the chase of exotic big game; such as John Barrows