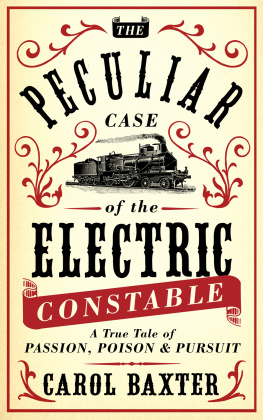

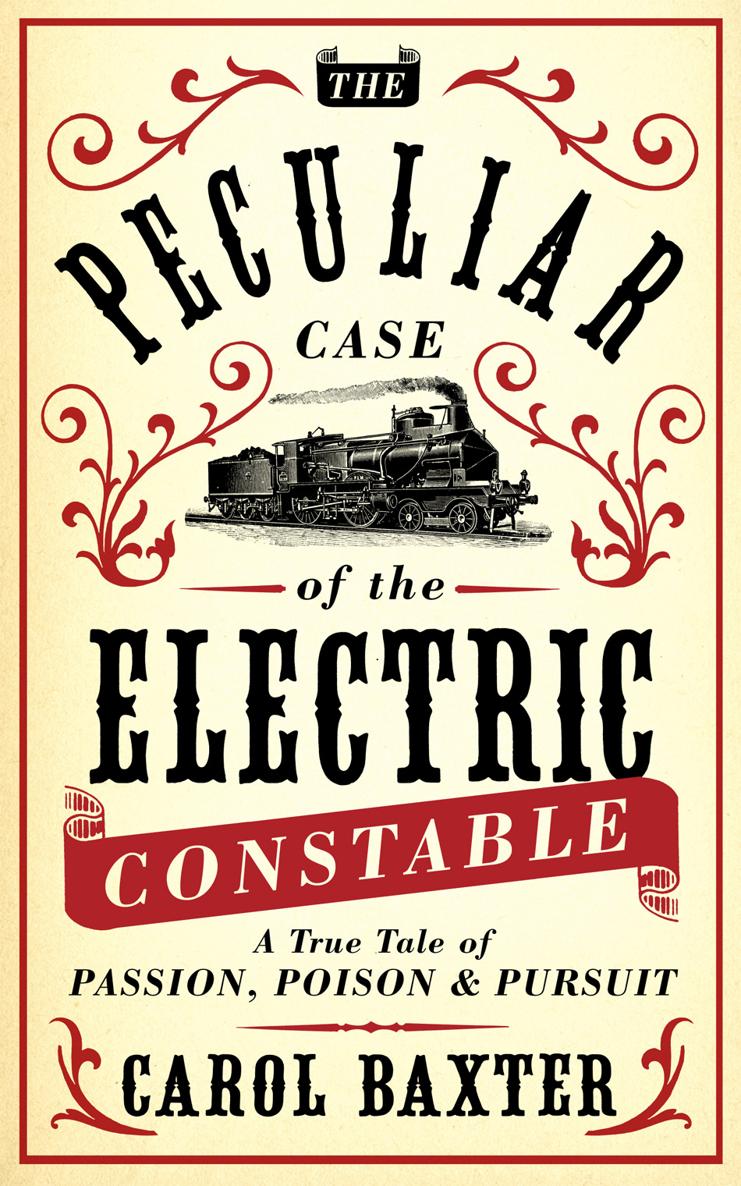

A Oneworld Book

First published by Oneworld Publications 2013

Copyright Carol Baxter 2013

The moral right of Carol Baxter to be identified as the Author of this book has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-78074-243-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-78074-244-1

Cover design by nathanburtondesign.com

Printed and bound by Page Bros Ltd.

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street, London WC1B 3SR

Prologue

Of all the physical agents discovered by modern scientific research, the most fertile in its subserviency to the arts of life is incontestably electricity, and of all the applications of this subtle agent, that which is transcendently the most admirable in its effects, the most astonishing in its results, and the most important in its influence upon the social relations of mankind and upon the spread of civilisation and the diffusion of knowledge, is the Electric Telegraph.

Dr Lardner,

The Electric Telegraph (1867)

EVERY NIGHT, as the clock strikes midnight, a new date emerges from the wings, initially blind to the events that will transpire as the next twenty-four hours unfold, the events that will mark its place in history. Most days pass by unnoticed or are soon forgotten in a particular locality, at least. Yet pluck any date from the historical calendar and somewhere on the worlds stage something momentous happened. Perhaps it had long been marked for glory. Perhaps it exploded cataclysmically into view. Often, though, while seeming inconsequential at the time, its importance is recognised only when historys binoculars are refocused on that particular stage.

Tuesday, 25 July 1837 was a date that Britains Professor Charles Wheatstone was hoping would in time be celebrated in the history books. It was late in the evening when he entered the carriage shed at Euston Station, the terminus of the London and Birmingham Railway then under construction. Hammering had ceased in time for the stations ceremonious opening five days earlier, an occasion already marked for posterity. Yet, despite the current lack of ceremony and the dingy surroundings, Wheatstone believed that this date would be of far greater importance if all went according to plan.

Small and slight, curly-headed, bespectacled and excruciatingly shy: the mould of the eccentric scientist might have been fashioned with Wheatstone in mind. He had long been fascinated by the workings of musical instruments and by acoustics, optics and electricity, and his inquisitive mind had led him to experiment with the possibilities of a communication system driven by electricity a so-called electric telegraph.

By the flickering light of a tallow candle, Wheatstone could see his recently patented electric telegraph machine squatting on the table in front of him. The model had a simple four-needle display that allowed only twelve letters to be indicated. Its clock face was a diamond-shaped grid, with lines heading north-east and north-west from each of the four needle bases that were positioned across a central horizontal axis. When two needles were simultaneously tilted towards each other at a forty-five degree angle from the vertical, they pointed along these lines towards a junction at which a letter was inscribed. To each needle was attached a single wire along which the electric current would pass. The wires trailed from the machine and became part of a thirteen-mile circuit wrapped around a frame sitting in the carriage shed, before heading out the door and disappearing into the shadows.

Wheatstone made a last-minute check all the wires were securely fastened to needles, all the needles moving freely like a teacher anxious for his prize student to shine. He then lifted his hands to the machines controls and deflected the two needles that would signal the first letter. Obligingly, the machine began transmitting his message.

A mile-and-a-half away in the winding-engine house at Camden Town sat his partner, William Fothergill Cooke, facing an identical instrument. An impecunious ex-military officer, Cooke was desperate to make money lots of money and had seen the commercial potential of an electric telegraph machine. Energetic and resourceful, he had the personality necessary to attract business but lacked the scientific know-how to construct a telegraph efficient enough to appeal to customers. He had approached the celebrated Professor Wheatstone for assistance.

Cookes passion and practicality galvanised Wheatstone. Although foresighted enough to have taken out patents for some of his inventions, Wheatstone had always prided himself on being a man of science rather than an entrepreneur until this visionary Gilbert encountered his pragmatic Sullivan. The pair imagined wires crisscrossing the countryside, with vast distances conquered in a fraction of a second but, thus far, the electric telegraph had been dismissed as just another newfangled thing. Cooke, however, had identified an ideal customer for their instrument: the railways. Not only would the telegraph allow speedy inter-station communication, it could be constructed to run beside the railway tracks an exquisitely efficient coupling.

The railways were suffering their own teething problems. Railway mania had gripped the nation after the Liverpool and Manchester line opened in 1830, but serious safety issues had yet to be resolved. A speeding train had little warning of trouble ahead. Departures were scheduled using a simple time-interval system. Train drivers had to rely upon vigilance and the occasional railway policeman stationed along the route to run the tracks safely. Even greater vigilance was required when both the up-and-down trains used a single, meandering track. In darkness, storms or fog, the lack of an adequate warning system had proved deadly.

It was a business problem in need of an enterprising solution and Wheatstone and Cooke were keen to display their system. Cooke was not alone when he waited at Camden Town on the evening of 25 July. The Railways chief engineers, Robert the Rocket Stephenson and Charles Fox, were standing by his side. Stephenson was the son of George Stephenson, also known as the Father of the Railways, while Charles Fox would go on to construct the majestic Crystal Palace. They were accustomed to scrutinising rough prototypes and seeing the future in all its glory.