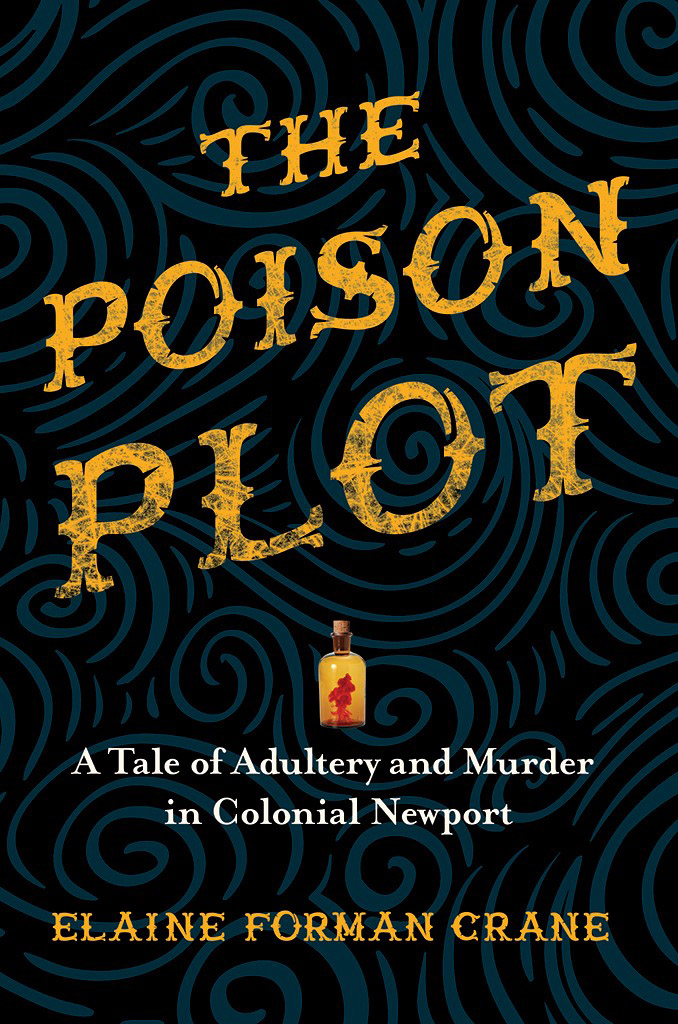

THE AUTHORS TALE

It is a chance encounter at the Rhode Island State Archives, where aged characters, detained for decades, congregate and clamor for attention. Some of those confined in the record boxes and leather-bound volumes have commanding stories to tell, although few can spin tales compelling enough to capture a historians attention. Yet the saga of Benedict and Mary Arnold has such an appeal. In some ways the couples narrative evokes The Canterbury Tales, stories told by voyagers that still echo more than six hundred years after their pilgrimage. As the medieval travelers trudge toward their destination, they while away the time by sharing stories that capture the underside of human nature. In just such a way, the drama surrounding Mary Arnolds alleged attempt to poison her husband in 1738 invites a modern raconteur to share the Arnolds foibles with a contemporary audience.

Benedict Arnolds unexpected intrusion into the present is followed by an introduction of sorts, in which he urgently bares his soul to a stranger who becomes captivated by his distressing circumstances. Benedicts tone convinces his audience-of-one that he is torn between vengeance and remorse. As the fifty-five-year-old Newport cooper airs his suspicions and denounces his spouse, Benedicts accusations express long-standing grievances that, he believes, could be resolved only by divorce. His considerably younger wife, Mary, the object of his fury, remains silent. She neither admits nor denies her efforts to terminate his life.

Arnolds dramatic tale inspires other eighteenth-century partisans to believe the worst of Mary and to corroborate the barrel makers account of his wifes duplicity. Boarders in the Arnold household disclose how they stumbled on Mary Arnold and Walter Motley in bed together. John Tweedy, the apothecary, reveals how Mary sought him out for a constant supply of laudanum, which would have led to the death of one spouse, or addiction for the other. Sarah Leach, another druggist, tells of Marys attempt to purchase the painkiller from her. One physician after another implicates Mary and her lover in a plot in which mercury or arsenic is the eventual poison of choice. Dr. Nathaniel Corles divulges how he treated the adulterous couple for gonorrhea before rebuffing their proposal that he join the conspiracy against Marys husband. Dr. Oliver Arnold, called in to assist his precariously ill relative, reaches an immediate and startling diagnosis: Benedict Arnold has been poisoned.

Other characters linger in the margins of the narrative: Isaac Martin-dale, who witnesses Marys admission of adultery and a heated argument between Arnold and Motley; Nurse Hudley, who may have offered the egg dram to Benedict Arnold in Marys place; Doctor Hooper, whose order of opiates gives Mary the opportunity to secrete the toxic painkillers; the mysterious Captain Troupe, who acts as a go-between for the illiterate conspirators; Marys brother and brother-in-law, who stand by Mary as intermediaries; the lawyer Thomas Ward, who draws up Benedicts generous will; and Patience Arnold, who is forced to side with either her mother or her father in this sordid affair.

As these narrators spin their individual talesand take up nearly one hundred manuscript pages in doing sothe spectator-turned-author imagines weaving the various evidentiary threads into something far more substantial than whole cloth. Reinforced by royalty whose low standards are easy to imitate, and by European writers whose scripts are replayed in the colonies, Mary and Benedict Arnold, as well as their entourage, become re-embodiments of the Chaucerian travelers.

But how to tell the story? How to frame the tale as a narrative that more closely resembles fiction than most nonfiction works, while remaining faithful to the historical record? How to compensate for the absence of Marys voice when every document corroborates and vindicates Benedict? How can Mary dominate the narrative if she leaves us nothing in her own hand? Her silence conceals the mischief she perpetrates and the characters she manipulates. Or does it?

In some ways the documents affixed to Benedicts divorce petition counterbalance Marys absence, even if they support his side of the story. Whether or not she defends herself in writing, Mary controls the narrative. Legal papersdepositions, witness statements, petitionssituate Mary as the central figure on whom the story depends. Sworn statements made under questioning in court or before a legislative body by ordinary folk suing their neighbors or being prosecuted for feloniesor simply recounting what they saw and heardreveal a great deal about people who do not leave other records behind. Such integrated accounts offer an opportunity to capture history through a narrative frameworka tale. And in order to emphasize the storytelling aspect of this work, much of the sleuthing on which it depends will be found in the back of this book as endnotes. As such, the notes become stories themselves, informative and entertaining textual partners, yet separated from the main body to preserve the flow of the narrative.

The Poison Plot extracts a small forgotten incident from early America and demonstrates how history can be explored through such episodes. It also aims to contextualize the main event and to expand its implications in time and space: backward to colonial Newport, forward to our own. As a result, this unlikely chronicle of marital duplicity is not only an engaging soap opera to which the reader is privy, but an entre into the larger community and a window into matters of historical importance. Marys voiceher side of the storyrequires speculation. But as the old saying goes, Murder will out. Presumably, attempted murder will rise to the surface as wellunless the ambiguity of the evidence leads a skeptical reader to doubt Marys culpability.

PROLOGUE

Because, alas! He is both blind and old,

His own sworn man shall make him a cuckold....

Just when his wife shall do him villainy;

Then shall he know of all her harlotry.

THE MERCHANTS TALE

FROM THE CANTERBURY TALES

Benedict Arnold was despondent and outraged. When he finally petitioned for divorce in December 1738, the irate husband claimed that he was the victim of a thwarted poison plot engineered by his adulterous wife and her lover. For reasons of her own, Benedicts spouse, Mary Ward Arnold, had tired of her husband and, to his chagrin, was cavorting with other men. Benedict, the grandson of a Rhode Island governor, a prosperous landowner, and a merchant-cooper by trade, was nearly two decades older than his frisky wife, whom he had married some time in the early 1720s, when she was barely twenty-one. How much Benedict knew of his wifes amorous affairs is unclear, but his confrontation with her latest live-in paramour reveals he feared for his life. He accused the couple of attempting to poison him.

Were Mary and her lover so motivated? If Mary was the driving force behind such a plot, her reasons never surface. Moreover, by choosing poison, she relied on the cooperation of others and broadened the number of people who would eventually point fingers at her. As the story unfolds, however, it becomes clear that Benedict could also level accusations at people and forces beyond the alleged perpetrators. Successive chapters reveal that apothecaries sold arsenic for the asking, physicians weakened patients with excessive bloodletting, and the most popular transatlantic fiction propagated ideas about spousal murder.