Table of Contents

For my mother,

Jean Cianci Davis Gatto

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

At the beginning of my Newport adventure, I was fortunate to meet the delightful Ralph Carpenter, who was called Mr. Newport by his many admirers. With great charm, wit, intelligence, and insight, he told me absolutely everything I needed to know about the city. In addition to being an invaluable and indefatigable guide, he represented the very best of Newport, and it was my privilege and my great pleasure to work with him.

Three guardian angels watched over me during my frequent trips to Newport. Thank you, Kitty Cushing, Stacie Mills, and Carol Swift, for your enthusiasm, your generosity, and your ability to make every moment festive and fun. Special thanks to Cheryl and Rick Bready, Judy Chace, Pamela Fielder and David Ford, Ronald Lee Fleming, Bettie Beardon Pardee, and Rockwell Stensrud.

My thanks to Sid Abbruzzi, Yusha Auchincloss, Win Baker, Letitia Baldridge, Virginia Baldwin, Nicholas Benson, Pamela Bradford, Minnie Cushing Coleman, Howard Cushing, Peter De Savary, Roger Englander, Auntie Helen Fenton, Angela Fischer, John Gacher, Richard Grosvenor, John and Mary Ellen Grosvenor, Kristine Hendrickson, George Herrick, Dyer Jones, Agnes Keating, Jerry Kirby, Didi Lorillard, Jonas Mekas, Jorey Miner, Carol OMalley, Brian ONeill, Leonard Panaggio, John Peixinho, Nuala Pell, Nancy Powell, Federico Santi, Marlen Scalzi, Nancy Sirkis, Carl Sprague, and John Winslow. I am very appreciative of the help I received from John Tschirch and Paul Miller at the Newport Preservation Society, and Bert Lippincott III at the Newport Historical Society. The Redwood Library and Athenaeum was an important resource, and my sincere thanks to Lisa Long, the Ezra Stiles Special Collections Librarian, for her extraordinary guidance.

I am grateful to my editor, Tom Miller, for his vision, dedication, and unfailing charm. My thanks to Dan Crissman at Wiley; Harvey Klinger at the Harvey Klinger Agency; my publicist, Robyn Liverant; and Wendy Silbert.

At home, I am indebted to my husband, Mark Urman, for his boundless creativity, optimism, and faith; my mother, Jean Gatto, for her patience and support; and my children, Oliver and Cleo, for the joy they give me every day.

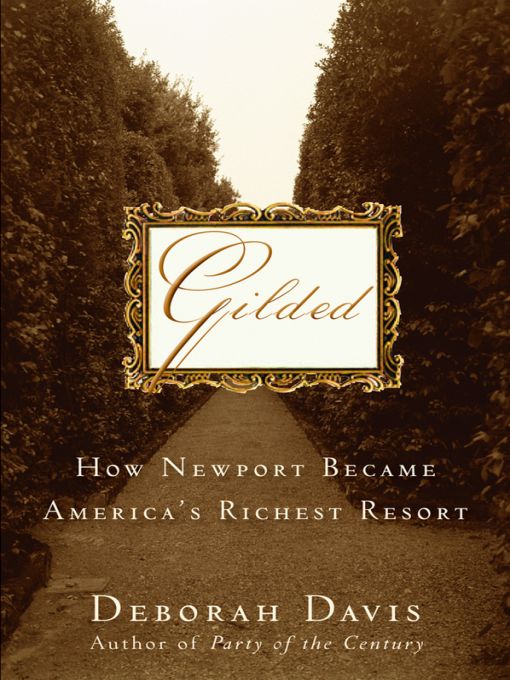

Introduction

When I was a child, I thought that Newport, Rhode Island, was an enchanted place. I loved it when my family drove there on pleasant summer days to see the citys famous turn of the-century castles. We called them mansions, a dead giveaway that we were outsiders. Real Newporters knew the proper term was cottage, a whimsical understatement considering they cost millions of dollars to build and had dozens of rooms and fancy exteriors. However, I discovered on these visits that most of Newports palaces were surrounded by gates, walls, and thick shrubs that prevented all but the most fleeting glimpses of the tantalizing world inside.

The Preservation Society had taken over some of Newports largest properties, including The Breakers and The Elms, in the 1950s and 1960s, and opened them to the public. These houses, once luxurious summer retreats for the countrys wealthiest families, were fascinating monuments to a lost way of life. For the price of admission, their secrets were laid bare. Anyone could enter but, as far as I was concerned, their accessibility made them infinitely less interesting than the houses that remained impenetrable. Paying to get in, I decided, was not the same as being invited. Private Newport still beckoned me. Who lived behind those gates, I wondered, and how did they get there?

When I was a teenager and could drive myself to Newport, I finally got inside a private estate on windswept Brenton Point, a dramatic location with a stunning, unobstructed view of the sea. The main house, called The Reef, had been destroyed by a fire in 1960, and only the blackened shell of the carriage house, known as The Bells, remained. My friends and I climbed the broken staircase, holding on to crumbling walls and old beams that threatened to give way at any moment. It didnt seem particularly safe (which is why the buildings charred shell is protected by a fence today) but we were young and fearless, and wanted to feel connected to the ruins romantic past.

Just a few years later, when I left home and went out into the world, I forgot about Newport. At various times, I heard the city was in declinethat cottages were being turned into condos and shopping centers and families were leaving and not coming back. I visited the beach a few times in the 1980s. And, in the early 1990s, my husband and I spent Valentines Day at an inn where a tuxedo clad waiter belted show tunes while serving us a candlelit breakfast in bed. The experience was supposed to give us a taste of how the rich in Newport lived, but I was certain that real butlers did not sing, nor light candles for that matter, at morning meals.

During those years, when I thought about Newportif I thought about it at allI compressed it as in that famous New Yorker magazine cover, with just a handful of signature buildings representing the entire landscape. Then, in 2003, I was invited to give a lecture at Rosecliff, one of the citys most beautiful and historic houses. As I drove on Bellevue Avenue, the spacious, tree lined street that the Vanderbilts, Belmonts, Astors, and Oelrichs (and even Von Bulows) called home, I was surprised to see homes in fine repair, with lush lawns, shapely shrubs, and freshly painted gates standing at attention. Since it was July, there were flowers everywhere. I actually stopped in front of an estate to admire some exotic blooms, only to realize I was looking at a bed of impatiens, the same flowers I had in my own garden in New Jersey. Somehow they looked more extravagantly colorful here in Newport. I smelled a wonderful perfume in the air, a blend of fresh grass, roses, privet hedges, and sea salt. But two other ingredients were mixed into this beguiling scent that were specific to the location: history and money. Blessed with an abundance of both, the city now looked better than ever. Newport was again an enchanted place, and the questions Id contemplated as a child came back to me in a rush. Who lived behind those gates? And how did they get there?

These are big questions, and I went hunting for answers in the city that one nineteenth century travel writer called the oldest and most picturesque watering place in this country. The public tour I took as a teenager had taught me that Newport was once a playground for self made moguls with the Midas touch. They turned everything in the city into goldsometimes quite literallyand ushered in Americas notorious Gilded Age. But as I began to do proper research, I learned that Newport had a long history that was marked by rise and fall and rise. More than once, the city was threatened with extinction, yet somehow it always bounced back. In fact, it seemed to be in the process of bouncing back right before my eyes.

I began to spend time in the local libraries, and the details I culled from old books, magazines, and newspapers were fascinating, even revelatory. I discovered that Newport wasand isa city defined by its women, so I wrote to Eileen Slocum, Bellevue Avenues leading doyenne, requesting an interview, and was thrilled when she wrote back, inviting me to tea.

This special appointment demanded special preparations. First stop, Google. An old