Table of Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

ALL THE LITTLE LIVE THINGS

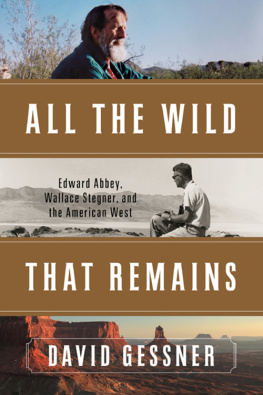

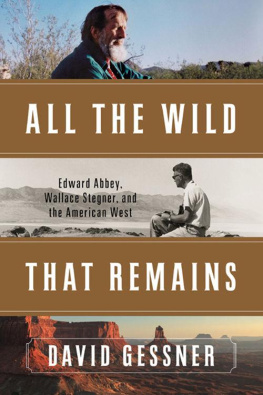

Wallace Stegner (1909-1993) was the author of, among other novels, Remembering Laughter, 1937; The Big Rock Candy Mountain, 1943; Joe Hill, 1950; All the Little Live Things, 1967 (Commonwealth Club Gold Medal); A Shooting Star, 1961; Angle of Repose, 1971 (Pulitzer Prize); The Spectator Bird, 1976 (National Book Award, 1977); Recapitulation, 1979; and Crossing to Safety, 1987. His nonfiction includes Beyond the Hundredth Meridian, 1954; Wolf Willow, 1963; The Sound of Mountain Water (essays), 1969; The Uneasy Chair: A Biography of Bernard DeVoto, 1974; and Where the Bluebird Sings to the Lemonade Springs: Living and Writing in the West, 1992. Three of his short stories have won O. Henry prizes, and in 1980 he received the Robert Kirsch Award from the Los Angeles Times for his lifetime literary achievements. His Collected Stories was published in 1990.

For Trudy, Franny, Judy, Peg

Oh, Sir! the good die first,

And they whose hearts are dry as summer dust

Burn to the socket.

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

How Do I Know What I Think Till I See What I Say?

A HALF HOUR AFTER I came down here, the rains began. They came without fuss, the thin edge of a circular Pacific storm that is probably dumping buckets on Oregon. One minute I was looking out my study window into the greeny-gold twilight under the live oak, watching a towhee kick up the leaves, and the next I saw that the air beyond the tree was scratched with fine rain. Now the flagstones are shining, the tops of the horizontal oak limbs are dark-wet, there is a growing drip from the dome of the tree above, the towhees olive back has melted into umber dusk and gone. I sit here watching evening and the winter rains come on together, and I feel as slack and dull as the day or the season. Or not slack so much as bruised. I am like a man so stiff from a beating that every move reminds him and fills him with outrage.

In the face of what has happened, Ruth is more resilient than I, she has taken up little life-saving jobs. It would not surprise me to see a FOR SALE sign on the cottage that for me still trembles a little, like settling dust in evening sunlight, with the ghost of Marians presence. But Ruth, making the cookies and casseroles and whole-wheat bread that she used to take there as offerings, puts the future under the pressure of sympathetic magic. She wills continuity, she chooses .to believe that before too long we will hear the slam of the old station wagons door down below, or have brought to us on the wind the voices of father and daughter talking to the piebald horse.

I? I came down here vaguely mumbling about finally starting on the memoirs. But the last thing I want to think about is what a retired literary agent used to do before he retired, and the people he used to do it among. I am concerned with gloomier matters: the condition of being flesh, susceptible to pain, infected with consciousness and the consciousness of consciousness, doomed to death and the awareness of death. My life stains the air around me. I am a tea bag left too long in the cup, and my steepings grow darker and bitterer.

Coming home this noon, Ruth and I said hardly ten words to each other. Our minds were back there on the lawn among the blunt stones. But when we eased over the stained and sagging bridge and saw the brush broken and trampled at its side, and a minute later when we rolled past the cottage with its weed-grown yard that I suppose expresses Marian without in the least resembling her, and a minute after that when the turning lane brought into view the gable of Pecks treehouse, something jumped the gap between us each time, a succession of those moments that you come to depend on during a long life together. But neither of us dared look fully at the reminding things we drove by. Ruth sat studying her hands, rubbing one white-gloved thumb over the other. In silence we drove through the open gates, between the big eucalyptus trees, and on up the steep shelf of road under the oaks.

October is the worst month for us. Nothing I saw pleased me. The oaks were dusty, with many brown terminal twigs killed by borers. The buckeyes were bare. Only a few dull-red leaves dangled from the poison-oak bushes. Brittle weeds grew into the edges of the road, and as we swung around the buttonhook and onto the hilltop I saw in the adobe ground cracks wide enough to break an ankle in.

And there on the right as we coasted toward the carport was the cherry tree, its leaves drooping and its foolish touching untimely blossoms wilted. Ruth drew an audible breath. Cherry blossoms in October were exactly the sort of thing from which Marian would have derived one of her passionate lessons about life.

Ruth got out of the car. Im going to lie down for a while. Shouldnt you?

Maybe Ill work around the yard.

The white hand was laid like a policemans on my arm. Joe, she said, dont take it out in highballs, now.

What do you think I am? I said, but her clairvoyance had put a barrier between me and a place I had half-consciously planned to visit. When I get sad or upset I can be a pantry drinker, and she knows it.

She pecked me with a kiss. Poor lamband then as our eyes met, Poor Marian. Poor all of us.

I followed her inside and changed the dark suit for old garden clothes and poked morosely out into the yard again. I found that I had maligned the day. Until the rain moved in just now it was one of those Indian-summer days, warm and windless, brown-colored, even the air faintly and purely brown like the water of some Vermont streams. It smelled leathery and curedthe oak leaves, maybe. On the bank the pyracantha was ripening heavy clusters, and the toyon along the hill was top-heavy with berries. I stood by the carport looking down across the gone-by vegetable garden and the baby orchard, and of course what stood up in my view as if it were a hundred feet high was that cherry tree.

My hands began to shake and my eyes got moistoutrage, outrage. To take all that trouble of digging, fertilizing, planting, spraying, pruning, coddling, only to have a blind vermin come burrowing brainlessly underground to destroy everything! My head was full of some poets bitter question: Was it for this the clay grew tall?

I walked down to look. The basin was disturbed by no more humps, of loose dirt, but something drastic had happened underground. The leaves that a few days before had been green now drooped like heat-withered cellophane. Along the branches, here and there, were the browning wisps of blossoms that the tree had frantically put out when the gopher began working on its roots. Before I even saw that it had begun, it was finished. Trying to produce flower and fruit and complete its cycle within a few days and way out of season, the tree was dead without knowing it. The sore sense of guilt that I felt told me I should have done something. But what?

I took hold of the sapling trunk and wiggled it, and with a slight threadlike tearing the whole tree came up in my hand. Except for the tiny root I had just broken away, there was nothing. The thing was as bare as a fishpole, gnawed off and practically polished about six inches below the surface.

Off in the brownish air a great flock of Brewers black-birds flashed into sudden dense visibility, roughened the sky a moment the way a school of fish can roughen the sea, and flashed off again, disappearing, as they all sheared edgewise at once. It was like something seen through a polarizer. The big red-tailed hawk that lives in Shieldss pasture was perched, I saw, high in a eucalyptus. Probably he was watching me with his X-ray eyes and wondering what I was doing, standing in my October orchard and brandishing the gnawed stub of what was once a promising Lambert cherry tree.