For Michael McDonough, who knows where all the acute angles are hidden in the grid

O BEAUTIFUL, FOR SPACIOUS SKIES, FOR AMBER WAVES OF grain, has there ever been another place on earth where so many people of wealth and power have paid for and put up with so much architecture they detested as within thy blessed borders today?

I doubt it seriously. Every child goes to school in a building that looks like a duplicating-machine replacement-parts wholesale distribution warehouse. Not even the school commissioners, who commissioned it and approved the plans, can figure out how it happened. The main thing is to try to avoid having to explain it to the parents.

Every new $900,000 summer house in the north woods of Michigan or on the shore of Long Island has so many pipe railings, ramps, hob-tread metal spiral stairways, sheets of industrial plate glass, banks of tungsten-halogen lamps, and white cylindrical shapes, it looks like an insecticide refinery. I once saw the owners of such a place driven to the edge of sensory deprivation by the whiteness & lightness & leanness & cleanness & bareness & spareness of it all. They became desperate for an antidote, such as coziness & color. They tried to bury the obligatory white sofas under Thai-silk throw pillows of every rebellious, iridescent shade of magenta, pink, and tropical green imaginab. But the architect returned, as he always does, like the conscience of a Calvinist, and he lectured them and hectored them and chucked the shimmering little sweet things out.

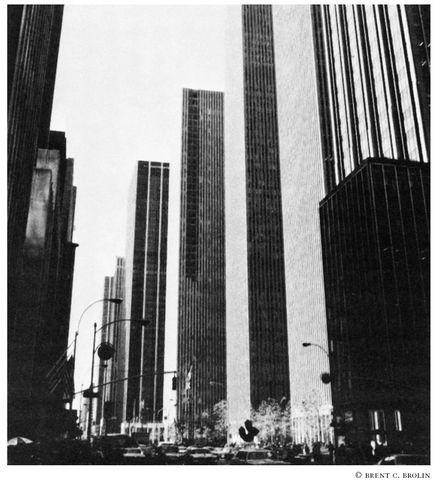

Rue de Regret: The Avenue of the Americas in New York. Row after Mies van der row of glass boxes. Worker housing pitched up fifty stories high.

Every great law firm in New York moves without a sputter of protest into a glass-box office building with concrete slab floors and seven-foot-ten-inch-high concrete slab ceilings and plasterboard walls and pygmy corridorsand then hires a decorator and gives him a budget of hundreds of thousands of dollars to turn these mean cubes and grids into a horizontal fantasy of a Restoration townhouse. I have seen the carpenters and cabinetmakers and search-and-acquire girls hauling in more cornices, covings, pilasters, carved moldings, and recessed domes, more linenfold paneling, more (fireless) fireplaces with festoons of fruit carved in mahogany on the mantels, more chandeliers, sconces, girandoles, chestnut leather sofas, and chiming clocks than Wren, Inigo Jones, the brothers Adam, Lord Burlington, and the Dilettanti, working in concert, could have dreamed of.

Without a peep they move in!even though the glass box appalls them all.

These are not merely my impressions, I promise you. For detailed evidence one has only to go to the conferences, symposia, and jury panels where the architects gather today to discuss the state of the art. They profess to be appalled themselves. Without a blush they will tell you that modern architecture is exhausted, finished. They themselves joke about the glass boxes. They use the term with a snigger. Philip Johnson, who built himself a glass-box house in Connecticut in 1949, utters the phrase with an antiquarians amusement, the way someone else might talk about an old brass bedstead discovered in the attic.

In any event, the problem is on the way to being solved, we are assured. There are now new approaches, new movements, new isms: Post-Modernism, Late Modernism, Rationalism, participatory architecture, Neo-Corbu, and the Los Angeles Silvers. Which add up to what? To such things as building more glass boxes and covering them with mirrored plate glass so as to reflect the glass boxes next door and distort their boring straight lines into curves.

I find the relation of the architect to the client in America today wonderfully eccentric, bordering on the perverse. In the past, those who commissioned and paid for palazzi, cathedrals, opera houses, libraries, universities, museums, ministries, pillared terraces, and winged villas didnt hesitate to turn them into visions of their own glory. Napoleon wanted to turn Paris into Rome under the Caesars, only with louder music and more marble. And it was done. His architects gave him the Arc de Triomphe and the Madeleine. His nephew Napoleon III wanted to turn Paris into Rome with Versailles piled on top, and it was done. His architects gave him the Paris Opra, an addition to the Louvre, and miles of new boulevards. Palmerston once threw out the results of a design competition for a new British Foreign Office building and told the leading Gothic Revival architect of the day, Gilbert Scott, to do it in the Classical style. And Scott did it, because Palmerston said do it.

In New York, Alice Gwynne Vanderbilt told George Browne Post to design her a French chteau at Fifth Avenue and Fifty-seventh Sreet, and he copied the Chteau de Blois for her down to the chasework on the brass lock rods on the casement windows. Not to be outdone, Alva Vanderbilt hired the most famous American architect of the day, Richard Morris Hunt, to design her a replica of the Petit Trianon as a summer house in Newport, and he did it, with relish. He was quite ready to satisfy that or any other fantasy of the Vanderbilts. If they want a house with a chimney on the bottom, he said, Ill give them one. But after 1945 our plutocrats, bureaucrats, board chairmen, CEOs, commissioners, and college presidents undergo an inexplicable change. They become diffident and reticent. All at once they are willing to accept that glass of ice water in the face, that bracing slap across the mouth, that reprimand for the fat on ones bourgeois soul, known as modern architecture.

And why? They cant tell you. They look up at the barefaced buildings they have bought, those great hulking structures they hate so thoroughly, and they cant figure it out themselves. It makes their heads hurt.

The Silver Prince

O UR STORY BEGINS IN GERMANY JUST AFTER THE FIRST World War. Young American architects, along with artists, writers, and odd-lot intellectuals, are roaming through Europe. This great boho adventure is called the Lost Generation. Meaning what? In The Liberation of American Literature, V. F. Calverton wrote that American artists and writers had suffered from a colonial complex throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and had timidly imitated European modelsbut that after World War I they had finally found the self-confidence and sense of identity to break free of the authority of Europe in the arts. In fact, he couldnt have gotten it more hopelessly turned around.

The motto of the Lost Generation was, in Malcolm Cowleys words, They do things better in Europe. What was in progress was a postwar discount tour in which practically any Americannot just, as in the old days, a Henry James, a John Singer Sargent, or a Richard Morris Huntcould go abroad and learn how to be a European artist. The colonial complex now took hold like a full nelson.

The European artist! What a dazzling figure! Andr Breton, Louis Aragon, Jean Cocteau, Tristan Tzara, Picasso, Matisse, Arnold Schoenberg, Paul Valrysuch creatures stood out like Gustave Miklos figurines of bronze and gold against the smoking rubble of Europe after the Great War. The rubble, the ruins of European civilization, was an essential part of the picture. The charred bone heap in the background was precisely what made an avant-gardist such as Breton or Picasso stand out so brilliantly.