1. The Prothonotary Warbler

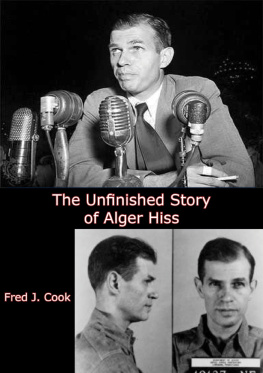

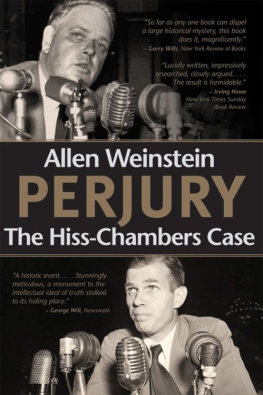

Alger Hiss, tall and boyish-looking in a tweedy, English-country-gentleman way, stood in Federal Court in New York on January 25, 1950, and spoke a few final words in his own defense. He had just been sentenced to five years in a federal penitentiary for perjurya charge that, because of the technicalities of the law, had been substituted for the real crime, treason. After reasserting his innocence, Hiss said:

I want to add that I am confident that in the future the full facts of how Whittaker Chambers was able to carry out forgery by typewriter will be disclosed.

This was a new charge, made belatedly after two marathon trials. And it was, at best, an oversimplification of the real issue. For the story told by Whittaker Chambers had received the full endorsement of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the U.S. Attorney Generals office: and if, in this sensational case, there is truly such an element as forgery by typewriter, it is almost inconceivable that Whittaker Chambers, alone and unaided, could have concocted the plot. He would have had to have collaborators.

Today, more than eight years after Alger Hiss injected the forgery by typewriter charge into this infinitely complicated case, it is still not susceptible of proof, but neither has it died the way flimsy and baseless charges, given time, die of their own accord. It persists, and by the very fact of its persistence, it is a disturbing nettle in the American conscience. For in the Alger Hiss case there can be no compromise. Either Alger Hiss was a traitor to his country and remains one of the most colossal liars and hypocrites, in history, or he is an American Dreyfus, framed on the highest levels of justice for political advantage.

One cannot hope to form an opinion on this vital question without first reviewing, at least in outline form, the step-by-step development of the case and then weighing, item by item, the crucial evidence on which judgment must pivot.

Never were two more starkly contrasting characters cast as the protagonists of national drama than Alger Hiss and Whittaker Chambers. Hiss, born in Baltimore in 1904, had had a distinguished career, mingling with the great men and playing a hand in shaping the great events of his age; Chambers, three years older, had struggled through a Dostoevski-like nightmarea disrupted home peopled by this cast: a mother who slept with an ax under her bed, a drunken grandfather, an insane grandmother who went around picking up knives, a younger brother morbidly fascinated with suicide and in the end, actually, a suicide.

For Alger Hiss, until the storm broke about him with Whittaker Chambers accusing testimony on August 3, 1948, life had seemed to follow one clear and continuous path of achievement. After a prep school education, he had entered Johns Hopkins University and had graduated with Phi Beta Kappa honors. He had then attended Harvard Law School, and during his last two years had been on the Harvard Law Review. When he left Harvard, his scholastic attainments were such that, in October, 1929, he won a coveted appointment as secretary to one of the most famous of modern Supreme Court Justices, the late Oliver Wendell Holmes.

This was merely the beginning. Subsequently, in 1933, after brief periods with prominent Boston and New York law firms, Hiss entered government service. He rose steadily in rank. In 1934, he was legal assistant to the Nye Committee in its probe of the profits of the munitions industry. He next served in the Justice Department under Solicitor General, later Supreme Court Justice, Stanley Reed. In 1936, he was transferred to the State Department as assistant to Assistant Secretary Francis B. Sayre, son-in-law of Woodrow Wilson. The war years brought Hiss into even greater prominence. He was secretary to the American delegation at the Dumbarton Oaks Economic Conference in 1944; he was in the American delegation that accompanied President Roosevelt to Yalta; he was secretary-general of the San Francisco Conference at which the United Nations was born. Finally, in December, 1946, he was elected president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace at a salary of twenty thousand dollars a year.

Whittaker Chambers career had been as checkered as Hisss had been smoothly distinguished. His twisted boyhood had left an indelible imprint on the man. He was later to admit under cross-examination in the Hiss trials that, while a student at Columbia University, he had written a Play for Puppets that blasphemed Christ and held up Christianity as a sadistic religion. He admitted writing pornographic poetry, admitted the theft of books from the Columbia University library admitted living in a New Orleans dive, the home of a prostitute known as One-Eyed Annie, when he was only seventeen. He admitted that he had frequently committed perjury, even after he had discovered conscience and had left the Communist party.

Despite this sordid past, Whittaker Chambers, too, had achieved a position of distinction in life. After he broke with communism, he eked out a precarious living doing book translations, then went to work for Time . A brilliant writer, possessed of fierce energy that sometimes enabled him to merge two working days into one without sleep, he rose to the status of senior editor at a salary of thirty thousand dollars a year.

These were the principals who were to clash in irreconcilable conflict before the House Un-American Activities Committee in the summer of 1948. The timing has, perhaps, a certain significance. It was at the beginning of a presidential campaign. Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had routed Republican adversaries with such ease for so long, had died, and Governor Thomas E. Dewey, of New York, was running against a lesser figure, President Harry S. Truman, and against a Democratic party split by civil rights in the South end Henry Wallaces candidacy in the North. Victory for the Republicans looked temptingly close.

Their party was in control of the House and in control of the Un-American Activities Committee. The committee chairman was J. Parnell Thomas, of New Jersey, who was later to spend nine months in federal prison on charges of padding his Congressional payroll and taking some eight thousand dollars in kickbacks from nonworking employees. Two of the most active committee members were Karl Mundt, now Senator from South Dakota, and Richard M. Nixon, now Vice President and a 1960 presidential hopeful. The Democratic members of the committee were Southern conservatives, and Washington political commentators noted at the time that it had on it no one who might be considered friendly to the Truman, administration.