Burtyrki Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

A Hidden World

My Nine Years in the Soviet Gulag

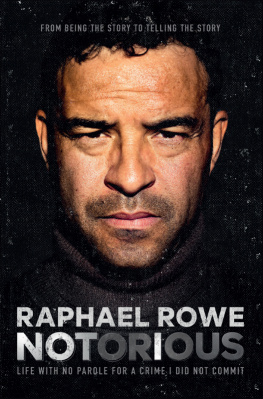

RAPHAEL RUPERT

Edited by Anthony Rhodes

Introduction by Edward Crankshaw

A Hidden World was originally published in 1963 by The World Publishing Company, Cleveland, Ohio, as A Hidden World: Nine Years of Confinement in Communist Prisons and Concentration Camps.

About the Author

Raphael Rupert, son of Hungarian Kossuth party Chairman Dr. Rudolph Rupert, was an opposition leader to Horthys pro-Nazi regime until the German occupation in 1944. At age eighteen, he began his law studies at Budapest University. Prior to the Second World War, Rupert joined the legal department of the Pester Commonwealth Commercial Bank and also served as a Reserve Cavalry officer. During the German occupation of Hungary, he joined the Underground and worked with the Western allies in saving many Jews, allied airmen, and Dutch people by helping conceal them from the Nazis. At the time of his arrest in 1947, Rupert was working out of the British Embassy in Budapest. His trial, based on a presumed confession, ended in his summary sentence to Camp 10 inside Russia, containing some of the countrys worst political offenders and numbering some 2,000 inmates of 28 nationalities. Following his release in 1956, Rupert was able to emigrate to Great Britain and settled with his second wife Anne in the mid-west of Ireland. Rupert was confined to a wheelchair after having lost both legs. In 1990, he was able to revisit Hungary and reunite with his family.

Introduction

By Edward Crankshaw

The first thing to be said is that this is a true story. I had the privilege of meeting Mr. Rupert when he finally escaped from Hungary in the autumn of 1956 and was still too dazed to talk much about his Russian experiences. But it was then at once clear that he was a man of exceptional honesty and that anything he cared later to say about his life in Soviet labor camps would be of especial value because of this. And so, I think, it turns out to be.

In writing of what he lived through in the hands of the Soviet political police he has not been tempted, as a more imaginative, more self-conscious individual would have been tempted, to strive for effect or to generalize from his personal experience, or even by meditating aloud on causes and effects to blur the particular image of what happened to him. Although he had already had glimpses of Soviet reality under Stalin he had no clear picture of what he would have to suffer and when he was finally sentenced to twenty-five years forced labor, on a trumped-up charge of espionage for the British, he went off on that appalling prison train as on a voyage of discovery. Indeed, one of the most fascinating aspects of his story is the Man-from-Mars view of the dark side of a continent.

It should not be thought that Mr. Rupert had no standpoint of his own. On the contrary, his standpoint was so firm that he took it completely for granted. It was that of the convinced, instinctive liberal individualist.

His father was a distinguished Liberal politician, and he himself had hoped to follow the family tradition. But the war came and, in lieu of politics, Mr. Rupert turned his hand to helping allied airmen and Jews to escape from the Germans. This seemed to him the most natural thing in the world. It was the liberal thing. Thus, when he told his Russian captors that he was a Liberal, and suffered terribly for it, what he really meant by Liberalism was simply the principle of freedom to be oneself. It is plain that even now he has not realized the massiveness of the forces working against this simple principle, and not only in Communist countries.

But even if I had never met Mr. Rupert I should have recognized at once the truth of his story. I should have had no doubt at all that everything happened to Mr. Rupert precisely as he has set it down, and it seemed to me that the value of the picture he builds up is all the greater because of the matter of fact limitations of his approach. It is this which gives a particular value too to Mr. Ruperts account of the last phase of his imprisonment and his final release some time after Stalins death. We are here taken into the world of prison camps in the process of breaking up and receive remarkable insights into the Soviet way of doing things when good, not evil, is the aim. More than this, in the extraordinary, interesting record of Mr. Ruperts final interrogations in the Lubianka prison (now no longer as an accused, but as a witness for the prosecution of Berias accomplices) we are given a glimpse from behind the scenes, which I think is unique, of the agonized process of deStalinization as it affected the apparatus of police terror.

For the rest, Mr. Rupert has simply told from day to day over a period of eight years what happened when an ordinary, unassuming Central European found himself caught up in the insane ferocity of ideological warfare.

It began when he was arrested in Budapest in 1947, and the reader will note with interest that he received more malignant personal violence at the hands of his fellow-countrymen, acting as Rakosis policemen, than during all his enforced stay in Russia. It continued when he was removed to Baden, the enchanting Habsburg spa in the wooded hills just outside Vienna, which the Russians chose as their Austrian Potsdam. And for me his descriptions of what went on during his imprisonment and interrogation, which ended in a false confession and a twenty-five years sentence in this cozy little holiday town, almost within visual signaling distance of the Allied occupation forces in Vienna itself, a morsel of the old Europe if ever there was one, has a special fascination which is not surpassed by any of the experiences, horrifying and macabre, which were to follow on the long train journey to Russia and in the labor camps themselves. No doubt this is because I knew more about the labor camps than I knew about the interior of Marshal Malinovskis idyllic Austrian headquarters!

Others will, I expect, be more interested by the insights offered by Mr. Rupert into aspects of the Soviet way of life.

It is these that I can vouch for. I have never been inside a Soviet labor camp, but a number of my friends, chiefly Russian, have shared the sort of life described by Mr. Rupert and some have lived to talk about it. Further, at one time and another, I myself have had close-up views of forced labor in action. There was a time, during and soon after the war, when life was at such a low ebb throughout the Soviet Union that in the remote areasand in some areas not so remoteit was often impossible to tell a free citizen from a prisoner. Certain northern landscapes seemed to be nothing but a Paul Nash nightmare of geometrically arranged fences of barbed wirefences punctuated by watch-towers on stilts, with machine-guns and searchlights, the guards heavily, stiffly cocooned in goatskin shubas nearly down to the ground so that they looked like wigwams; there were the prisoners, being marched about, or doing fatigues, or man-handling heavy timber, or trying to break up frozen soil and sub-soil to sink foundations. And next to them came free laborers, with nothing in their appearance or the work they were doing to show the difference. Nobody cared: they were all half dead of hunger anyway. I have seenI have told this elsewheregangs of prisoners from a camp in North Russia laying strategic railways, building new wharves, breaking up the ice laboriously with broken tools at forty degrees below zero centigradeand alongside them there have been gangs of free citizens, volunteers, doing the same work, and marching back at the end of their shift to communal barracks. Many of these were girls. I have seen the sort of swift public copulations described by Mr. Rupert. And I have had fall dead at my feet a prisoner shot by a guard for falling out of line to pick up a crust of bread thrown from the galley of an iced-up merchant shipand seen how the corpse was left lying like a dead cat in a slum street, until after a few days there was nothing to be seen but a faint hummock under sifted snow.