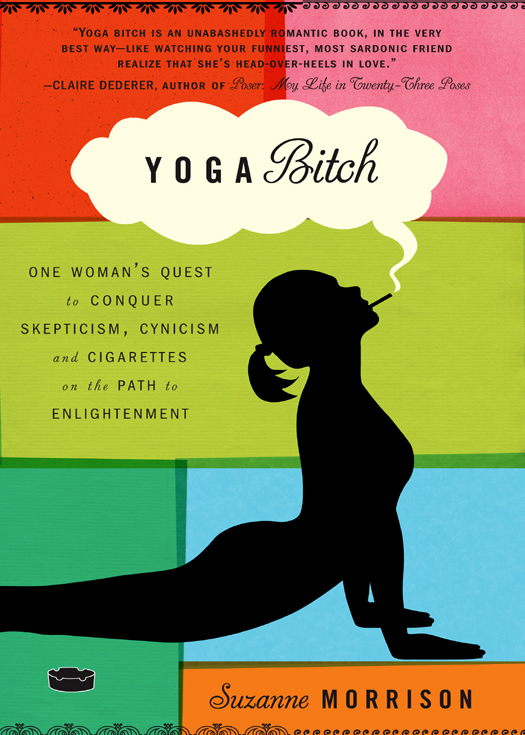

Copyright 2011 by Suzanne Morrison

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Three Rivers Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

Three Rivers Press and the Tugboat design are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Morrison, Suzanne.

Yoga bitch : one womans quest to conquer skepticism, cynicism, and cigarettes on the path to enlightenment / Suzanne Morrison.1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Morrison, Suzanne. 2. Spiritual biography. 3. Yoga. I. Title.

BL73.M667A3 2011

204.36092dc22

[B]

2010041940

eISBN: 978-0-307-71745-0

Cover design by Jessie Sayward Bright

v3.1

for

KURT ANDERSON

Contents

1. Indrasana

and before Kitty knew where she was, she found herself not merely under Annas influence, but in love with her, as young girls do fall in love with older and married women

LEO TOLSTOY , Anna Karenina

Today I found myself strangely moved by a yoga teacher who spoke like a cross between a phone-sex operator and a poetry slam contestant. At the start of class, she asked us to pretend we were floating on a cloud. As she put it, Youre oh-pening your heart to that cloud, youre floating, youre blossoming out and tuning in, youre evanescing, yeah, thats right, youre evanescing.

I briefly contemplated giving the teacher my yoga finger and walking out. Ive been practicing yoga for close to a decade now, and at thirty-four Im too old for that airy-fairy horseshit. As far as Im concerned, floating on a cloud sounds less like a pleasant spiritual exercise and more like what you think youre doing when youre on LSD while falling out of an airplane. But I tuned out her mellifluous, yogier-than-thou voice and soon enough found myself really meditating. Of course, I was meditating on punching this yoga teacher in the face, but still.

At the end of class, she asked us to join her in a chant: gate, gate, paragate, parasamgate which means, she said, her voice shedding its yogabot tones, gone, gone, gone beyond. She was young, a little cupcake of a yoga teacher in her black and gray yoga outfit. Maybe she was twenty-five. Maybe younger. She said her grandmother had recently passed away, and she wanted to chant for her and for all of our beloveds who had already gone beyond. In that moment, I forgave her everything, wanted to button up her sweater and give her a cup of cocoa. I chanted gone, gone, gone beyond for her beloveds and for mine, and for the twenty-five-year-old I once was.

I turned twenty-five the month after September eleventh, when the stories of those who had gone beyond that day were fresh and ubiquitous. I was working three jobs to save money to move from Seattle to New York, and whether I was at the law firm, at the pub, or taking care of my grandparents bills, the news was on, and it was all bad. So many people looking for the remains of the people they loved. So many images of the planes hitting the towers, the smoke, the ash.

I had never really been afraid of death before that year. I thought I had worked all that out by the age of seventeen, when I concluded that so long as one lives authentically, one dies without fear or regret. As a teenager, it seemed so simple: if I lived my life as my authentic self wished to live, then death would become something to be curious about; one more adventure I would experience on my own terms.

Religion was an obstacle to authenticity, I figured, especially if you were only confirming in the Catholic Church so that your mother wouldnt give you the stink-eye for the rest of your life. So, at seventeen, I told my mother I wouldnt be confirming. That Kierkegaard said each must come to faith alone, and I hadnt come to faithand she couldnt make me.

This was all well and good for a teenager who secretly believed herself to be immortal, as my countless speeding tickets suggested I did. But by twenty-five the idea of death as an adventure struck me as idiotic. As callous, heartless, and, most of all, clueless. Death wasnt an adventure; it was a near and ever-present void. It was the reason my throat ached when I watched my grandfather try to get up out of his chair. It was the reason we all watched the news with our hands over our mouths.

I had recently graduated from college, having postponed my studies until I was twenty-one in order to follow my authentic self to Europe after high school. Now I was supposed to leave for New York by the following summer. Before the attack on lower Manhattan, I had been nervous about moving to New York, but now what was supposed to be a difficult but necessary rite of passage felt more like courting my own annihilation.

Everywhere I looked, I saw death. My move to New York was the death of my life in Seattle, of a life shared with my family and friends. Given the precariousness of our national security, it seemed as if moving away could mean never seeing them again. I remember wondering how long it would take me to walk home from New York should there be an apocalypse. I figured it would take a while. This worried me.

Even when I wasnt filling my head with postapocalyptic paranoid fantasies, death was out to get me. Once we got to New York, my boyfriend, Jonah, and I would move in together, and I knew what that meant. That meant marriage was coming, and after marriage, babies. And only one thing comes after babies. Death.

I came down with cancer all the time. Brain cancer, stomach cancer, bone cancer. Even trimming my fingernails reminded me that time was passing, and death was coming. Those little boomerangs of used-up life showed up in the sink week after week.

I measured out my life in toenail clippings.

Stop thinking like that! my sister said.

I cant.

Just try. You havent even tried.

My sister, Jill, has always been the wisest, the most grounded, of my three siblings. But she couldnt teach me how to live in the face of death, not then. But Indra could.

Indra was a woman, a yoga teacher, a god. Indra taught me how to stand on my head, how to quit smoking, and then lifted me off this Judeo-Christian continent, to fly over miles and miles of indifferent ocean, before dropping me down on a Hindu island in the middle of a Muslim archipelago at the onset of the War on Terror. Indra was my first yoga teacher and I loved her. I loved her with the kind of ambivalence Ive only ever had about God, and every man Ive ever left.

Indra introduced me to the concept of union. Thats what hatha yoga is all about, uniting mind and body, masculine and feminine, and, most of all, the individual self with the indivisible Selfwho some call God.

When I was seventeen, I was proud that I had chosen not to confirm into the Catholic Church. I figured everybody I toldall those sane people in the world who did not share my crazypants DNAwould agree with me. I was right; most of them, especially my artist friends, did. But one teacher, my drama teacher, said something Ive never forgotten. After rehearsal one day, she listened indulgently while I bragged about my lack of faith, a half-smile on her face. Then she said, Its okay to fall away from the Church when youre young. Youll come back when people start dying.