William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2020

This edition first published by Endeavour Press Ltd. in 2015

First published in 1998 by Viking

Copyright Charles Spencer, 1998

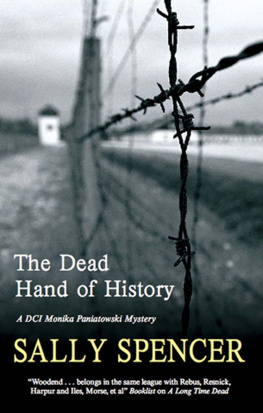

Cover image Getty Images

Charles Spencer asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Ebook Edition September 2020 ISBN: 9780008373191

Version: 2020-07-28

I cant remember exactly when I realized that Althorp would come my way. Certainly I was conscious of the fact by the time of my grandfathers eightieth birthday in 1972, when the local paper in Northamptonshire took a photograph of him, me and my father, and referred to the three generations in rather dynastic terms.

It was an unsettling thought for an introspective and shy little boy: this leviathan of an edifice being my responsibility, my home. I remember a cousin, who had traditionally made no secret of his wish to lord it at Althorp, looking momentarily optimistic when, aged seven or eight, I declared to him that I would never live there.

My reservations stemmed from two facts: I had not lived there in my early childhood, and could not contemplate leaving the security of Park House, in Sandringham, where we were based with my father: and Althorp seemed such an old mans house, reflecting my grandfathers Edwardian tastes, in a chilling time-warp complete with the permeating smell of Trumpers hair oil and the ubiquitous tocking of grandfather clocks their ticking always seemed too subtle a sound, getting absorbed in the oak of the floorboards and the fabric of the tapestries.

Another problem was actually getting to Althorp. It was over two hours in the car from Park House, and that was an age in my fathers too-smooth Jaguar, with the result that we would reach the Park gates after several stops for car-sickness. There would then be the stately pace through the Park, as my father absorbed the magic of this most English of settings, where the twentieth century was not welcome and where natural beauty was the perpetual theme.

We would nudge past lambs, a reminder of my ancestors great flocks from medieval times, ignore the turn-off to the Falconry, and cruise on to the cattle grid. There were no sleeping policemen then, which made the grid that much more of a feature. And there, on the right, would be the faade of a house that had been home to nearly five centuries of Spencers, and would one day, they told me, swallow me up too. The Stables, with their mellow, yellow glow of ironstone, looked so much softer, so much more inviting the warmth of the feminine, in contrast to the houses steely masculinity.

I have never, ever, heard anyone call the exterior of Althorp beautiful. Not even architectural historians, whom you might expect to stick up for their own, have defended it thus. The dappled grey of the external tiles emits no feeling of joy, the shallowness of their form betrayed by the drabness of their effect. How I have longed that my great-great-great-grandfather had ignored fashion and stuck with the original red-brick faade, rather than let Henry Holland impose his grey, Georgian tastes on a Tudor and Stuart gem. But the work was done; and, on a practical level, it has ensured the outward survival of Althorp, without too much maintenance, for over two centuries. The trouble is, it looks like a practical solution. No romantic would ever countenance such a course.

So imagine a small boy, arriving after a long journey at the most imposing of settings, with family expectation oozing from every elderly pore of every adult relation, and you will understand part of the reason why Althorp, and its inheritance, was not something that I overly looked forward to.

It all seems very spoilt and immature now, I appreciate; but I had no idea that I would ever be able to impose my own tastes and priorities on something so historic, so very settled, for my grandfather was not known as the curator earl without reason, and for him Althorp was a living conservation exercise, where he could catalogue and maintain, with enormous diligence, while sharing the collection generously with fellow members of the intelligentsia, and reluctantly with those who in no way matched his vast knowledge.

My memory of those days is of orderly druggets, dust sheets and uniformity. My grandmothers joie de vivre was limited to Grandmothers Sitting Room, with beautiful, deep blue, hand-painted frescoes and formal furniture that reflected her cool and natural aristocracy; a slice of sophistication in an otherwise stolidly traditional English stately home.

The last time I remember being with my grandmother was outside this room, through the French windows in her Rose Garden, her head swathed in bandages after an unsuccessful operation to root out a brain tumour, giggling as we played with her hose-pipe, neither splashing the other but threatening to, before we hugged each other tight, me breathless with childish excitement, she knowing that there would not be too many hugs left with her grandchildren during this lifetime. She died that November.

My grandfather dominated the rest of Althorp. He combined the authority of his inherited status with the assuredness of encyclopaedic knowledge. He could recite not only the creator of every piece of furniture, but also how much it cost, when and where it was repaired, as well as stating from which room in which Spencer property it had originated.

Grandfather pored over the family records in the Muniment Room, a musty apartment beyond the dinginess of his own secretarys garret, where 500 years of Spencer papers were amassed: medieval household accounts, letters from leading Jacobean political figures, and reminiscences of Victorian house parties, all stored together.

Grandfather once found Sir Winston Spencer-Churchill, busy researching for his biography of their mutual ancestor, the First Duke of Marlborough, smoking a cigar in this holy of holies, and made him douse it immediately in a glass of water. Im not sure who would, on reflection, have been more taken aback at this: Churchill for the uncompromising abruptness of his host, or my grandfather, who would not have considered whom he was ordering about until alter the immediate threat to his archives had been extinguished. As a rule, Grandfather was very conscious of peoples status.