Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2017 by Charlie Clark

All rights reserved

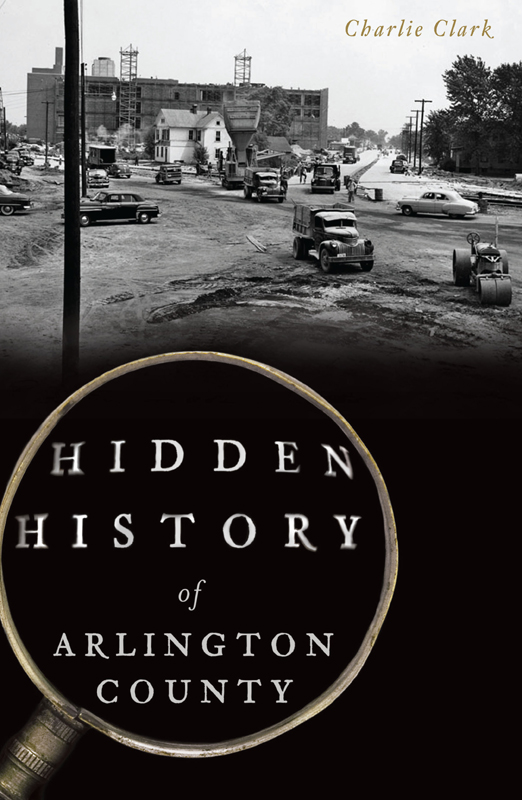

Front cover: Arlington County Public Library.

First published 2017

e-book edition 2017

ISBN 978.1.43966.159.8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017934950

print edition ISBN 978.1.62585.923.5

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

As an Arlington native, I loved learning many things about my hometown for the very first time. Charlie Clark is a wonderful tour guide for anyone who wants to uncover the rich and sometimes colorful history of a place Ill always consider home.

Katie Couric, news broadcaster

As author and raconteur, Charlie Clark has become an Arlington institution in his own right. He draws from a wealth of knowledge, gained beginning at his mothers knee, to reveal little-known aspects of our fascinating community. His columns are a highlight of my week.

Karl VanNewkirk, president, Arlington Historical Society

This ones for three high-impact Arlington teachers: Harry Tuell (Yorktown High School), who set me free in journalism; Jacqueline Jeffress Guter (Williamsburg Junior High), whose help with French broadened my horizons; and Betty Ann Armstrong (fifth and sixth grade at James Madison Elementary), who bequeathed me the basics.

CONTENTS

English roots of our county name; George Washingtons tree marker; expanding the story of slavery at Arlington House

Clues of slavery at a Civil Warera home; transporting a nineteenth-century home; a famous play was written in this bedroom

A county song few recall; Democrats exiled across the county line; a football rivalry that drew ten thousand fans

First in Virginia to desegregate school; wicked Wilson Pickett sings at school gym; a globally watched local response to 9/11 87

Old Blood n Guts Patton at Fort Myer; two county heroes we lost in World War II; the Nauck community pharmacist; visits from a fried chicken icon; local boy makes good in The Sound of Music

Our forgotten local madam; American Nazis multiple headquarters; a high school narc unmasked

Three local ghost stories; challenging a non-conforming house; an Arlington neighborhood some think is Falls Church

INTRODUCTION

Where does a communitys identity come from? And how do forcesinternal and externalaffect that identity over time?

At 26.5 square miles, Arlington is the smallest, most densely populated county in the United States. Its destiny has been driven by its geographic proximity to Washington, D.C., andvery importantby the fact that most Potomac River crossings begin in the county.

Initially part of a large land grant to Lord Fairfax before the Revolutionary War, what is now Arlington was ceded to help form the new federal government seat by the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1790. It remained a part of the District of Columbia until 1847, when Congress retroceded it back to the commonwealth.

As the Civil War loomed, Arlington (then Alexandria County), foreshadowing its modern role within Virginia, did not join the rest of the commonwealth in supporting secession. Union forts ringed much of the periphery of the county. By the late 1890s, trollies linked Washington, D.C., and Ballston, creating a turn-of-the-century company townthe company being the federal government.

In 1920, Alexandria County became Arlington County, a name drawn from the Arlington Plantation along the Potomac River and Arlington House, both of which took their names from English entities via Virginias Eastern Shore (as author Charlie Clark will explain). To this day, Arlington House is the centerpiece of the countys seal. In a perhaps apocryphal story, the 1920 name change is linked to a misunderstanding surrounding a military parade planned to celebrate the end of World War I. The event was supposed to include a flyover by aircraft at Fort Myer, but the pilots buzzed Old Town Alexandria instead. That was it for our community bigwigstime for a new name!

Until the 1940s, Arlington moseyed along like many southern towns. Main streets like Columbia Pike, Wilson Boulevard and Lee Highway offered shopping and a bit of dining. Schoolsblack and whiteserved children and teenagers. Black and white neighborhoods were well established, and churches of many faiths were scattered throughout the county. A number of longtime Arlington families of both races led their neighborhoods. Arlingtons overall nature was residential and subsidiary to the big capital city across the river.

But the arrival of World War II changed that. Arlington greeted an influx of well-educated, determined Americans and their families, all drawn to President Franklin Roosevelt, his policies and government service. The feds looked no farther than Arlington as the best location to provide an unprecedented amount of new affordable housing, constructing the first such development at Colonial Village above Rosslyn. It was followed soon by Fairlington on the countys southern border and Arlington Village on Columbia Pike.

These new neighbors, along with many longtime African American families, are the roots of the modern era. They believed in excellent public education, using research to understand tough problems and planning, planning, planning with the community to achieve the shared vision of Arlington as a great place to live, work and raise a family.

Policy debate at the neighborhood and countywide level was a hallmark of these midcentury years. Arlingtons stay-at-home, college-educated moms functioned as an underappreciated think tank throughout this era. Both the League of Women Voters and the local chapter of the American Association of University Women studied and debated numerous public policy options. The Committee of 100 emerged as an educational forum for many of the hottest topics of the day. Arlingtonians for a Better County was formed to allow federal employees subject to Hatch Act limitations on political activity the opportunity to participate in nonpartisan electoral politics at the county board level.

As a result, in the 1950s, Arlington became the first Virginia community to move to integrate its public schools. For this stand on principles, Arlingtonians lost their capacity to elect school board members for nearly forty years. One of the lead attorneys for the historic one man, one vote case served on the Arlington County Board. And the seeds of what we today call transit-oriented development came as a positive policy response to the communitys fears that Arlington would become northern Virginias parking lot. After much debate, the newly proposed Metro was located in the heart of Arlington with planned development rather than on an interstate highway median.