EUMENES Publishing 2019, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

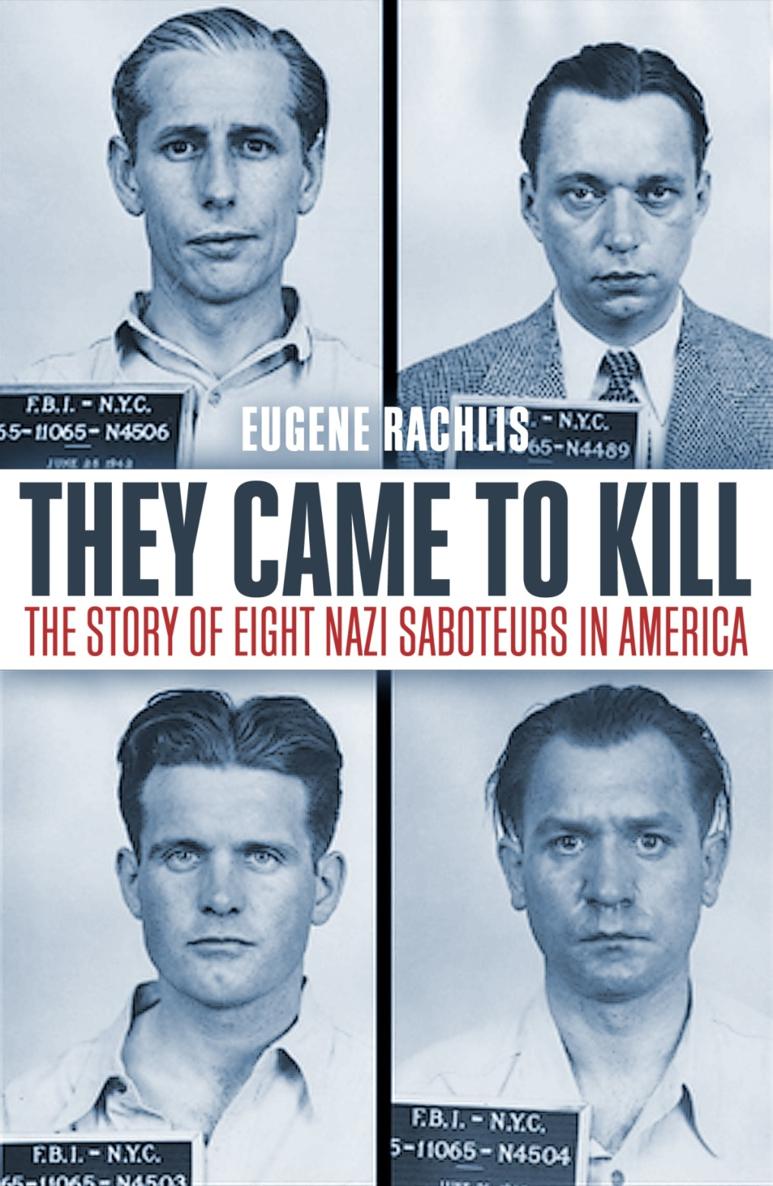

THEY CAME TO KILL

The Story of Eight Nazi Saboteurs in America

EUGENE RACHLIS

* * *

...they would have stilled the machines and endangered the lives of thousands of defense workers...they came to maim and kill.

J. Edgar Hoover, Director, F.B.I., March of Time radio broadcast, July 9, 1942

They Came to Kill was originally published in 1961 by Random House, New York.

* * *

To my mother and father

with love and gratitude

Part I SCHOOL FOR SABOTAGE

1. CODE NAME: PASTORIUS

At eight oclock on the evening of June 12, 1942, Lieutenant Commander Lindner of the German submarine U-202 noted in his log that he was twenty miles off the coast of Long Island, due south of East Hampton, and about a hundred miles east of New York City. He was wrong, but not by very much. The U-202 was actually opposite Amagansett, another summer resort town three miles to the east. An error so slight was of itself testimony to a remarkable display of navigational skill. Lindner had taken the U-202 more than three thousand miles in fifteen days, the last two of them from off Nova Scotia in exceedingly heavy fog, to a shoreline he had never seen. Now, with fog still pressing sullenly about him, Lindner ordered the U-202 submerged, and the power switched from her Diesel engines to silent electric motors. As the submarine moved slowly north toward shore, Lindner spoke briefly to a short, thin-faced man, wearing khaki Navy work clothes, and walked to the mess room. In a few minutes he was joined by the thin-faced man and three others dressed like him, and by two of the submarines crew. In curt, concise sentences Lindner described the U-202 s position and estimated the time it would take at her present rate of speed to reach a point offshore from which the two sailors could safely launch a boat. Landing these four men was Lindners assignment, and now that it was all but complete, he was understandably anxious for it to be done right. He was a combat officer with a fine recordon his last mission he had sunk three Allied ships off Greenlandand had not been entirely enthusiastic about a voyage in which he had firm orders to avoid enemy action. Lindner was looking forward to getting rid of his passengers and returning to the open Atlantic, to a submarine commanders proper business of seeking out merchant convoys to torpedo.

What Lindner had to do now was risky. The fog had killed his hope of examining the shoreline by day and basing his plans for the landing on what he saw. The lack of visibility could be an advantage, of course, but it also called for supreme caution. Lindner was as concerned about getting his rubber boat and his sailors back to the U-202 as he was about landing the four men. He ordered the two sailors to inflate the boat and attach a towline to it, and he gave one of them a flashlight and a rocket. If they were not hauled back after tugging a few times on the towline, they were to blink the flashlight, doubtful help in a fog like this; the rocket was to be discharged only if they ran into trouble on shore. The sailors left the mess room while the others continued talking. At 11:00 p.m. they heard a soft scraping sound; the submarine had touched the ocean floor. Lindner ordered the U-202 raised and moved forward again. When she scraped bottom the second time, he ordered her to the surface and turned her parallel to shore. He opened the hatch and called the thin-faced man to the deck. What do you think of the night, Dasch? he asked. Christ, this is perfect, the man answered.

They were some fifty yards from the beach and could not see it.

The thin-faced man went below and told his three companions to make a final check of their pockets to see that they held nothing of German origin. The men made nervous, perfunctory pats at their clothing; one of them had a small bottle of German brandy, another a pack of German cigarettes, but neither was brought out. Just before midnight, Lindner came down from the deck to say that the rubber boat was inflated and alongside, and his sailors ready. He joined the four men in a drink and left to go topside again. The four men followed a few minutes later, one of them carrying a large sea bag. When they were on deck, sailors below handed up four solidly built wooden crates, which looked like so many fruit cases, each about two feet long, eight and a half inches deep and a foot wide. The men placed them carefully in the rubber boat to assure a proper balance. The man with the sea bag stepped into the stern of the boat and was followed by the others, holding paddles. Then came the two sailors with their paddles, and last of all, the thin-faced leader.

With the weight of the six men and the four boxes, the boat sat heavily in the water, but rowing was not difficult at first. As a sailor on the U-202 payed out the towline, the boat moved swiftly away. In a few minutes the submarine was completely out of sight and the sound of surf rose from a murmur to a roar.

Suddenly, in the overwhelming darkness, the men in the small boat lost all sense of direction. The sound of breaking waves seemed to come first from the left, then the right. Despite the weight, the boat was now being tossed about on the huge waves, and the ocean spray was soaking the men. One of them, trying to keep his balance, knocked his cap into the water; the others knelt low and paddled harder. Then, in a moment of frightened silence, they heard the surf straight ahead. The waves about them rose higher and threatened to swamp the boat. The leader shouted an excited and not very encouraging, Come on, boys, lets go to it, just as a wave struck, nearly capsizing the boat and causing two men to drop their paddles in the water. But the force of the wave had also been enough to get them over the breaking surf. It was followed by another, which propelled them forward so fast they did not realize they were aground until the wave had receded.

The two sailors immediately leaped out and pulled the boat beyond the waters edge. The four men followed. Two of them quickly began unloading the boxes; the man hugging the sea bag walked a few yards inland and put it down before he returned to help. The leader ignored the unloading of the boat as he walked a wide circle of the beach around them. Satisfied, he came back and urged that the boxes and bag be moved up into the dunes at once. He led the way for about a hundred yards, as two men carried boxes and one dragged the sea bag. The two men dropped their boxes beside a fallen sand fence and returned to the boat as the third man opened the bag, pulled out a raincoat and stretched it flat on the wet sand. Then he reached into the bag and withdrew damp and wrinkled civilian trousers, jackets, vests, shirts and socks, four pairs of shoes, two short shovels of the kind the military calls entrenching tools, and a small canvas bag, all of which he dropped on the raincoat. By the time the sea bag was empty the others had returned with the last of the boxes, and the thin-faced man from an exploration beyond the dunes. He had seen what appeared to be a tall beacon tower; this disturbed him, and he urged the others to change quickly from their wet Navy uniforms to the civilian clothes. He himself stripped to his trousers, put on a shirt and tie, a red sweater and a brown fedora, and ran back down to the two sailors, who were struggling to turn the boat over to drain it.