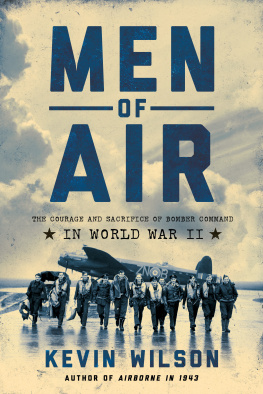

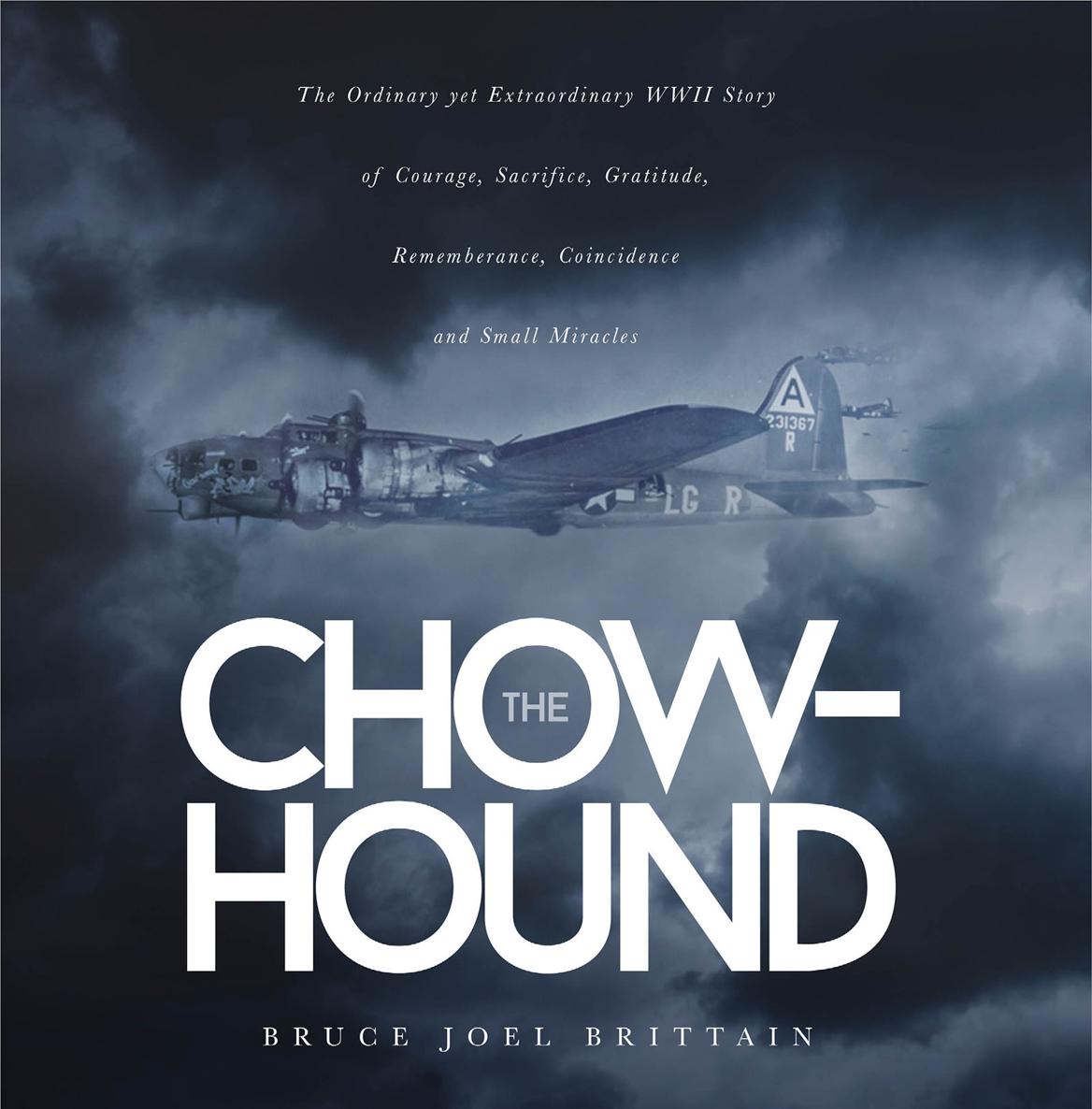

THE CHOW-HOUND:

The Ordinary yet Extraordinary WWII Story of Courage, Sacrifice, Gratitude, Rememberance, Coincidence, and Small Miracles

by Bruce Joel Brittain

Copyright 2019 Bruce Joel Brittain

ISBN 978-1-63393-855-7

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior written permission of the author.

Published by

210 60th Street

Virginia Beach, VA 23451

8004354811

www.koehlerbooks.com

DEDICATION

This book is dedicated to Joanne Gillies Thompson, Dolly Gillies Jacobs and all of the extended families of the nine Chow-hound crewmen who gave their all in defense of free and open societies.

PROLOGUE

In the early afternoon of August 8, 1944, one of the lead B-17s in a thirty-six-plane US Eighth Air Force mission for the 91st Bomb Group (91st BG), flying out of Bassingbourn, England, took a direct hitamidshipfrom a German 88 anti-aircraft shell. The blast occurred just a few minutes before the bomber, the Chow-hound, would have reached its target which included German infantry, armor and artillery positions a few miles south of Caen, France.

The powerful explosion separated the tail from the fuselage and the doomed aircraft rolled and spun violently, so violently that one wing snapped off. The three parts of the aircraft then plowed into French farmland, hundreds of yards apart, just outside the village of Lonlay lAbbaye. All nine crew members perished.

This incident is but a footnote in a war that, in its worldwide scope, dwarfs the individual losses of men and machines. None of the crew members were famous. None were heroically rescued and spirited through enemy lines to fly and fight again. All were typical American boys, none older than twenty-six, who had answered the call to arms. They were aware of the danger on each mission, yet, time after time, they climbed aboard and assumed their stations. They were doing their job in the very barbaric enterprise of war. Not one of this crew likely thought himself a hero or wanted to be.

The Eighth Air Force lost 4,145 heavy bombers to enemy fire or bad luck from early 1942 through late 1945. In the process, more than 26,000 young American airmen died. The loss of this particular bomber and its nine-man crew is just one small statistic, masking the full tragic story of an individual doomed aircraft and its crew who failed to come home. Time and again, similar scenes played out across Africa, Europe, the Pacific and Southeast Asia.

Yet, there is something different about this one aircraft, something that echoes through the decades since the twisted metal and ravaged bodies came to rest in the fertile soil of Normandy.

The circumstances of this one aircraft and of one particular crewman serves as an illustration of who stepped up to fight the existential threat posed by the Axis Powers. The eventual aftermath also reveals the dogged determination of Americas military to leave no soldier unaccounted for. The Chow-hound story also shows the deep gratitude of the French residents of Normandy who honor fallen allied troops, three-quarters of a century after their liberation. This story bears positive witness to lives allowed and now thriving in a country that was once forced to fight for its very existence. This war took young American men half a world away to fight and die, but their legacy lives on, some in the flesh. Finally, it also demonstrates how the random chance of luck created fame for the Chow-hound , far beyond what would likely have been its place in history.

Most military history books deal with the broad sweep of war: moving armies, decisive battles, political elements and masterfulor incompetentleadership. If not those big stories, history focuses on the heroic individual or small group: Audie Murphy, Louie Zamperini, Seal Team Six, Marcus Luttrell or the five Sullivan brothers.

This book is focused differently; it looks at one ordinary tragedy in war and finds the extraordinary in its aftermath, not because the extraordinary is the only topic worthy of a book, but because every death in war sends out a pattern of ripples that, when followed, lead to events that are often surprising, sometimes inspiring, sometimes tragic but always interesting.

CHAPTER 1

MILK RUN

By early August of 1944 the Allies had pushed their offensive lines south from the Normandy beaches and had moved 30 to 50 miles inland across the Normandy peninsula, steadily pushing south before wheeling east to advance on Paris. The Americans, advancing from Utah and Omaha beaches to the west were more aggressively taking territory in the drive to liberate Paris. To their east were British and Canadian forces that had come into Normandy at Sword, Gold and Juneau Beaches. These troops were led by British General, Field Marshal Montgomery. The Brits and Canadians, however, were slower to advance than the Americans. Montgomery had always been more cautious than his

American counterparts.

The more rapid advance by the Americans exposed their left flank to devastating German counterattacks. General Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Commander in the European Theater, ordered General Omar Bradley to have the US Eighth Air Force assist the English and Canadian troops push forward, to get in line with the American advance, and then to break through the German Seventh Army defensive line. In some cases, American units had to pull back from captured ground to the west in order to solidify the Allied line. Montgomerys plan, code named Totalise , had the potential to surround the German Seventh Army, led by General Kurt Meyers. The advancing Canadians were to lead what is now known as the Normandy Breakout.

Montgomerys plan relied on heavy bombers to soften up the German lines. So, loaded with 250-pound anti-personnel bombs, American B-17s were to target German lines, 10 to 15 miles south of Caen near the village of Bretteville-sur-Laize. This village gave its name to the sortie flown Tuesday, August 8, 1944. Nearly 500 bombers took part in the mission.

These missions into the fringes of France were far less hazardous than the deep penetration missions into Germany and occupied France. On those longer missions, Luftwaffe fighter planes, unchallenged by Allied fighter escorts, whose fuel range limited their ability to guard the big bombers deep into the continent, wreaked havoc among the heavily-armed but lumbering bombers.

But by August, the Allied Air Forces had virtually eliminated the threat of Hermann Grings fighter planes in western France. The Germans primary and final defense against Allied air power in Normandy was their lethally accurate anti-aircraft 105mm and 88mm guns, manned by well-trained crews.

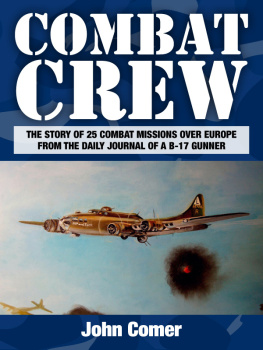

Among Americas thirty-nine heavy bomber group airfields scattered across eastern England was the Ninety-first Bomber Group (91st BG). The 91st operated out of Bassingbourn Air Field, about 40 miles due north of central London and 10 miles southwest of Cambridge. Bassingbourn was home to the Memphis Belle , a bomber that gained fame by completing twenty-five combat mission in Europe and then returning to the US, barnstorming the country to sell war bonds. Configured like the other thirty-eight bomber groups in the Eighth Air Force, the 91st included four squadrons of twelve active and one reserve bomber each. On any given mission, three of the squadrons would participate and one would stand down, providing the crews a needed break from the steady and dangerous daily missions. On days when the Mighty Eighth mounted a full-strength attack on Germany, it could launch nearly 2,000 B-17s, crewed by 19,000 very young Americans.