Contents

Guide

ALSO BY KEVIN WILSON

Blood and Fears

Airborne in 1943

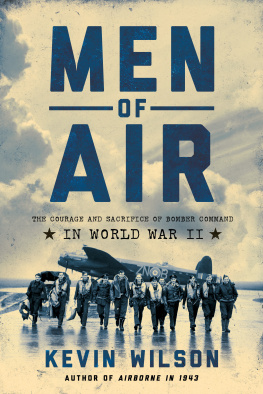

MEN

OF

AIR

THE COURAGE AND SACRIFICE OF BOMBER COMMAND

* IN WORLD WAR II *

KEVIN WILSON

M EN OF A IR

Pegasus Books, Ltd.

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2019 by Kevin Wilson

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition February 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN: 978-1-64313-006-4

ISBN: 978-1-64313-099-6

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

To Declan, Julia, Nicholas and Martin

Contents

SECTION ONE

SECTION TWO

When we first arrived on 101 Sqn the intelligence officer told us: Youre now on an operational squadron, your expectation of life is six weeks. Go back to your huts and make out your wills. It was simply accepted that two out of three of us would be killed.

Sgt Dennis Goodliffe, a 19-year-old flight engineer, who completed a thirty-three-operation tour in sixteen weeks in the spring and summer of 1944.

A s always for those who waited in the night across the flat fields of bomber country, the first faint droning they now heard in the southern sky was both welcome and worrying. First came relief at hearing the young heroes of the night return from raiding Germany, then the nagging question of how many there would be. In this particular, frosty dawn such anguish was acute. For this was the end of the first raid in 1944 in the Battle of Berlin, a campaign that was draining the lifeblood from Bomber Command.

As the Lancasters descended in the darkness, lurching up Englands eastern edge, pilots and bomb aimers peered fretfully into the gloom for the first uncertain glimmer of navigation beacons. Airframes creaked, whistled and whispered, advertising fresh flak holes from the target all crews feared. Engineers tapped fuel gauges and anxiously eyed oil temperatures as the ragged armada thundered on, swinging ever deeper into the blackness. And slowly, as altimeters wound back, the sense of unspoken unity that had kept this loose gaggle of airmen linked across miles of sky was lost. Now each individually coded contributor to the cacophony sought its own airfield. It was then that the reverberation of their passing rattled slates in sleepy villages as the Lancasters began the closing letdown to base, debriefing and fuggy billet.

On the airfields WAAF drivers waited by their trucks to pick up crews from dispersal, intelligence officers sharpened pencils and wits to pick from weary airmen the latest clues to Luftwaffe tactics, and beaming chaplains stood poised in ops rooms by tea urn and rum jar to dispense warmth and comfort for tension-stretched nerves. Crews not flying that night stirred beneath rough blankets at the sound of bombers touching, then gratefully holding, the glistening concrete of the stretching runway. First elements of the force of 421 bombers that had struggled into the overcast at midnight, turned off the flarepath and trundled, power plants popping, into the open arms of dispersal bays and shut down. Hot engines cooled and ticked clock-like in contraction from the efforts of the night, as crews climbed down stiffly into the silence, then stood awkwardly, almost shyly, anticipating the crew truck driven by their welcoming WAAF.

In the chill of ops rooms, station commanders and other earthbound souls gathered anxiously to count the tally as the airmen trudged in, heavy-legged in their flying gear, and flopped into stiff-backed chairs ranged in rows before smart intelligence staff. The officers waited, bright-eyed and with pencils poised, as they faced the weary warriors, ready to interpret the halting accounts of the night. In fact, it was the same old story of attrition for insufficient return.

The ops boards would show a final toll of twenty-eight Lancasters missing, a percentage loss of 6.7 the latest appalling statistic in an eroding campaign that seemed without hope of remission. The gloom of 1/2 January in this fifth year of war had seen Bomber Command raid the Reich capital for the ninth time since the Battle of Berlin had opened the previous November, and for the second time in four nights. Before the campaign began the Commands C-in-C, Sir Arthur Harris, had promised Churchill it would cost Germany the war and Britain between 400 and 500 aircraft. It was not ending the war for Germany, but so far it had cost Bomber Command 211 aircraft and the crews in them.

The latest raid had been mounted despite little hope of Pathfinders being able to visually mark the target. The reality had been a reliance on uncertain skymarkers, which drifted above nine-tenths cloud and caused a scattering of bombs among the thickets of the Grnewald southwest of Berlin. Only one industrial building had been destroyed. In fact, it had been another encouraging night for the Luftwaffe. The operational plan had called for route markers, to keep the bomber force on track. The Luftwaffes seasoned Nachtjger had then been able to orbit and swoop between these flares, which signalled the bomber streams progress to the target as clearly as a glaring window in the blackout. A total of 168 airmen who had climbed into the darkness nine hours before were now dead and thirty-four were prisoners. In Berlin itself only seventy-nine people had died.

Unknown to the aircrew, who now bottled up their terror and instead spilled out tales of frustration, the Battle of Berlin still had three months to run. The toll among the bomber boys on these raids and those on other German cities in the period would be greater even than in the nineteen weeks of the Battle of the Ruhr in 1943. It would be the apogee of Luftwaffe success, demonstrated by the losses in the final operation of the Battle of Berlin, by Leipzig in February and by Nuremberg at the end of March. In February, 1,529 aircrew would fail to return; in March which would see the highest loss by Bomber Command on any single raid by far 1,880. But it was the month that had just begun which would prove the cruellest in that bleak winter. In thirty-one days a total of 2,256 aircrew were lost, only 464 of whom were later found to be prisoners of war. January 1944 was the worst period of the war to be an airman in heavy bombers.

It wasnt just the likelihood of death but the method of dying that kept young aircrew awake in their billets. The choices were stark. If they didnt perish from searing flak or fighter bullet, they might fall without parachutes from suddenly disintegrating aircraft, drown in the cold waters of the North Sea, or for a few, slowly suffocate from lack of oxygen. This was the year when the aircrew strength of Bomber Command reached its zenith and the time when a broader scythe than ever swished through its ranks. The cream of Britain and young bloods of the Commonwealth died in this period well-educated youngsters with a desire to experience the adventure of flight who had stepped forward, then been subjected to rigorous physical and mental tests before being passed for aircrew training. The comparison with subalterns of the First World War who suffered an equal attrition has been made before and is worth repeating. The elite of the Second World War generation had volunteered to fly and, in the attrition of 1944, found the likelihood of survival in the bomber war so slim they were no more substantial than men of air, ghosts already, waiting to vanish this night or the next.