First published by Viking in 1988

Reprinted in this format in 2010 by

Pen & Sword Aviation

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Martin Middlebrook, 1988, 2010

ISBN 978 1 84884 224 3

The right of Martin Middlebrook to be identified as

author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including

photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval

system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England

by CPI

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select,

Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper,

Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

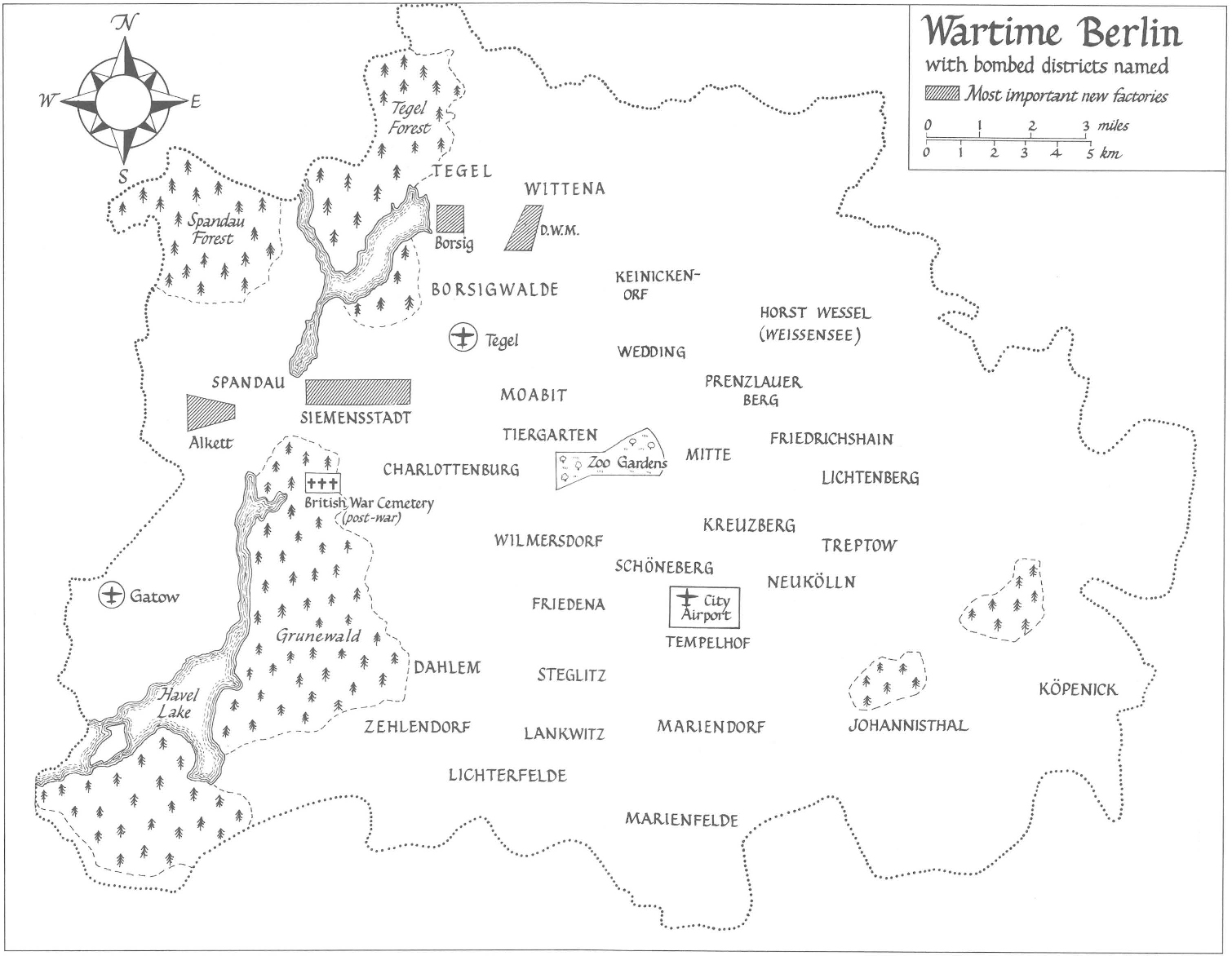

Maps

Diagram

Maps drawn by Reginald Piggott

Other books by Martin Middlebrook

The First Day on the Somme*

The Nuremberg Raid*

Convoy

The Sinking of the Prince of Wales and Repulse*

(with Patrick Mahoney)

The Kaisers Battle*

The Battle of Hamburg

The Peenemnde Raid*

The Schweinfurt-Regensburg Mission

The Falklands War

The Argentine Fight for the Falklands*

Your Country Needs You*

The North Midland Territorials Go To War*

The Middlebrook Guide to the Somme Battlefields*

(with Mary Middlebrook)

The Bruckshaw Diaries (ed.)

Everlasting Arms (ed.)

Arnhem 1944*

* denotes titles in print with Pen & Sword Books Ltd

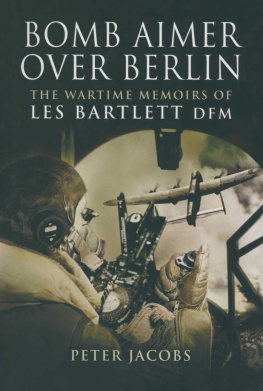

At twenty-four minutes to eight in the evening of 23 August 1943, a Lancaster bomber took off from an airfield near Lincoln. A further 718 aircraft followed from other airfields, carrying 1,800 tons of bombs. Their target was Berlin. Seven months later, in the early hours of 25 March 1944, 739 bombers returned from another raid to Berlin, on this night leaving 72 aircraft lost over German-occupied territory or having crashed into the sea. Between these two events, a further seventeen heavy attacks were made on Berlin. More than ten thousand bomber sorties were dispatched against the German capital during this period; more than thirty thousand tons of bombs were dropped in or near the city. Even before it started, the R.A.F. was calling this campaign the Battle of Berlin, a title accepted by history after the war.

The period of the bombing war in which the Battle of Berlin fell was in what Sir Arthur Harris, in his post-war dispatches, would call the Main Offensive. Emerging from a mostly experimental preliminary phase of Harriss operations at the end of 1942 and uncommitted to helping with the Normandy invasion until April 1944, Bomber Command could devote its entire effort to attacks on Germanys main cities. What may be called the bomber dream was now put to the test. This was the hope that strategic bombing on a large enough scale and relentlessly pressed home would cause the collapse both of German industrial production and of the spirit of the German people. If this was successful the war would end. There would be no need for a prolonged land campaign after the invasion, with all its fears of a repeat of a 191418 Western-Front-type slaughter. Most of Germanys industrial cities were attacked during this period, but Harriss Main Offensive was further divided into three campaigns against selected areas. From March to July 1943, the main weight of attack fell on the industrial areas of the Ruhr. Severe damage was caused, and, although the strong German defences in this area took their toll of the bombers, Bomber Commands natural growth at this time left it in stronger form at the end of what became known as the Battle of the Ruhr. There followed in July and early August 1943 the short campaign against Hamburg when Germanys second city suffered devastating damage, mostly as a result of a firestorm which occurred on one night, and the city temporarily ceased to contribute to the German war effort. That was the Battle of Hamburg.

With these undoubted successes achieved and with the longer nights of autumn, Bomber Command was ready for what Harris intended to be the final battle, the offensive against Berlin to which the whole of the coming winter could be devoted. Weather conditions and tactical considerations would demand that other targets besides Berlin be attacked, but nineteen major raids would be carried out against that main target. It had required only four attacks to put Hamburg out of action! If the hopes of the R.A.F. commanders could not be achieved by the following spring, they would never have another chance to defeat Germany by bombing alone. If the 194344 period was Harriss Main Offensive, then the Battle of Berlin was the climax of that main offensive and Bomber Commands greatest test during the war.

Let there be no misunderstanding of Sir Arthur Harriss expectations. I make no apology for reproducing yet again his famous letters to Churchill and to his superior, Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal, Chief of the Air Staff. To Churchill in November 1943:

We can wreck Berlin from end to end if the U.S.A.A.F. will come in on it. It will cost between us 400 and 500 aircraft. It will cost Germany the war.

And to Portal in December:

The attempt to bring in the Americans was not successful, partly because they were following a jointly agreed selective policy and partly because it would have been prohibitively expensive in casualities for their daylight bomber force to raid Berlin before its long-range fighter escort became available, and that would not happen until the Battle of Berlin was almost over. The second of Harriss claims, made after it was clear that the Americans would not join in the battle, was dependent upon Bomber Command receiving priority in the production of Lancaster bombers. Bomber Command did receive that priority.

Who believed in these claims by Harris? Certainly not the Army and the Navy, nor the Americans. Even Harriss superiors at the Air Ministry were in two minds over the concentration on Berlin more about this later. What of Harriss aircrews, his shock troops who had to go over the top thirty times before gaining a rest from operations? They may have been briefly impressed and inspired with talk of destroying Berlin from end to end and finishing off the war, but these young men were more concerned with such matters as surviving the next raid, getting in some drinking with the crew, their position on the leave roster, making progress with the current girlfriend and scrounging some more coke for the stoves of their chilly Nissen huts.