For Arthur and Joseph

First published in Great Britain in 2007 by

Pen & Sword Aviation

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

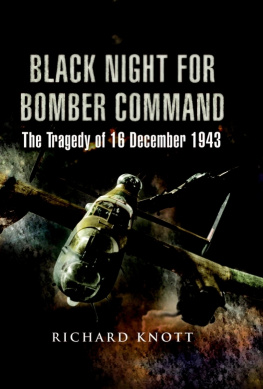

Copyright Richard Knott 2007

9781781594421

The right of Richard Knott to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Sabon 11/13pt by Concept, Huddersfield

Printed and bound in England by Biddles Ltd

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen and Sword Select, Pen and Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

INTRODUCTION

I t is a scene familiar from dozens of black and white war films, and it chimes with so many family memories across Europe: lone serviceman on a station platform, kitbag at his feet, going back to active service, in this case flying over Germany on dark nights, often in cruel weather. This is Donald Penfold, a rear gunner with 97 Squadron. It is 1943. On the platform edge is a small boy for whom this airman is his Uncle Donald. The boy, Peter, is nine years old and will never forget this moment, although he was never to see his Uncle Donald again. Soon after returning to the war, Penfold, along with many other RAF aircrew, died when the Lancaster in which he was flying crashed as it attempted to land in thick fog in the dead of night.

During a lunch party sixty-three years later, close to the point where this book was finished, a chance conversation revealed that I was talking to Donald Penfolds nephew, someone whom I had known for fifteen years or more without ever touching on this link with the past. Later, his wife wrote to me: Peters main memory is of the two uncles Don and Len, in 1943, standing with him... on the station at West Worthing, about to return to their home in Surrey before Uncle Donald went back to the War. They looked at each other and said: What shall we give him? and to Peters delight and amazement they each gave him a florin (i.e. 2/ 10 new pence). I could see the three of them, suspended in time, on a day of bright summer sun, long ago.

For me, having spent three years of my life researching the events of one grim night in RAF history Black Thursday it was one of those moments when the people caught up in that drama emerged from the shadows, the more so when I realised that Uncle Don had died in Lancaster P for Peter. The connection between the two Peters hints at the story this book seeks to tell. Black Night for Bomber Command has been written with an eye to peoples history, rather than the detail of aerial combat and bomb loads. Necessarily it describes the raid on Berlin that began the tragedy, but the emphasis thereafter is on the struggle between airmen and the elements, and what makes the former worthy of memory and record.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A book of this kind relies hugely on the good will and memories of many people. I am enormously grateful to all of them. Without exception, where I have asked for help and advice it has been freely given. My father-in-law, Arthur Spencer, has been a constant source of information, a critical friend, and a great encouragement throughout this enterprise. All writers should have such a companion on the way. One of my oldest and best friends, Thain Hatherly, read the manuscript at a critical stage and was a wise counsellor on matters great and small. He gave hugely of his time in commenting on the draft and I am extremely grateful to him.

Of the survivors of Black Thursday, Roger Coulombe was a most willing and encouraging witness to the events of 16 December 1943. Our continuing e-mail correspondence across the Atlantic never fails to warm my heart. Other survivors who provided me with information and insights included J Peter Green, Henry Horscroft, E Hedley, Len Whitehead, Ken Duddell, Mike Hedgeland, Bill Kilmurray, Ted Mercer, Charles Clarke, Ronald Low, John H Ward, Bill Pearson and Sandy Sandison.

I am particularly grateful to Bob Wilson for permission to quote from his autobiography Behind the Network and to include photographs of his brother Billy; to Jennie Gray for the initial inspiration; Dick Barton for information about the crash at Eastrington; Rich Allenby; Roger Stephenson; Robin Lingard; Dave Cheetham; Ron Parker; Des Evans; Ian McGregor at the National Meteorological Archive; Brian Boulton for information, research and photographs relating to the crash at Iken; Angela and Peter Awbery White; Bob Adams for information about Malcolm Western; John Whiteley; Ray Barker; Pauleen Balls; Julian Hendy; Max Liddle; Ian Reid and Ian Walker, for the loan of photographs of his father Arthur Walker, together with his log book.

I would also like to thank the following for help and advice at various points in the research: my wife, Vanessa; Chris Thomas; John Thorp; Tom Gatfield; John Rees; Bill Napier; James Heneage; Dr Gerald Rolph at Allerton Castle; Vern White; Peter Parnham; Alex Wedderburn; Horace Bennett; Arthur White; David Fell; I D Golder and Graham Pitchfork.

The following organisations have been invaluable resources: the Yorkshire Air Museum; the National Meteorological Archive; the National Archives; National Defence Headquarters, Ottawa, Canada; the Memorial Room at RAF Linton-on-Ouse; the RAF Museum; the Imperial War Museum; Lincolnshire County Archives; the Second World War Experience Centre; the Yorkshire Evening Press; City of York Libraries; York City Archives and Ipswich Record Office.

I have sought to acknowledge in the text and footnotes the provenance of my sources. I am very grateful to those on whom I have drawn. Every effort has been made to seek permission to quote wherever practicable. I am conscious, however, that I have failed to track down the family of Sergeant Bernard Clark whose diary I draw on in chapter three. I hope that this recognition of his heroism and humanity compensates for the unsanctioned use of his diary, found on the BBCs Peoples War website.

Finally I apologise for any errors I may have inadvertently made, or sources I have not fully recognised or thanked. This book could not have been written without the diligence of others who put pen to paper before me.

I am not pressing you to fight the weather as well as the Germans, never forget that.

Sir Winston Churchill

I also decided that the book Id write would not be a novel, but simply a true tale cut from the cloth of reality, concocted out of true events and characters.

Soldiers of Salamis, Javier Cercas

CHAPTER ONE

COLD DECEMBER NIGHT, 1943

T hey watched the gathering mist slowly roll across the airfields as the afternoon faded, expecting the raid to be scrubbed. It was midwinter and mid-war 16 December 1943 and the target was Berlin. Across eastern England thousands of young men readied themselves, periodically pausing to gauge the developing weather on that sombre winter afternoon. The anticipated cancellation never came.