Black

Cat

Raiders

of WW II

BLACK

CAT

RAIDERS

of WW II

Richard C. Knott

BLUEJACKET BOOKS

Naval Institute Press

Annapolis, Maryland

This book has been brought to publication by the generous assistance of Marguerite and Gerry Lenfest.

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

1981 by the Nautical and Aviation Publishing Company of America

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

First Bluejacket Books printing, 2000

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Knott, Richard C.

[Black Cat Raiders of World War II]

Black Cat Raiders of WW II / Richard C. Knott.

p. cm.

Originally published: Black Cat Raiders of World War II. Annapolis : Nautical & Aviation Pub. Co. of America, 1981.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-61251-241-9

1. World War, 1939-1945Aerial operations, American. 2. World War, 1939-1945Pacific Ocean. 3. United States. Army Air ForcesHistory World War, 1939-1945. I. Title: Black Cat Raiders of WW 2. II. Title: Black Cat Raiders of WW Two. III. Title.

940.544973dc21

00-31868

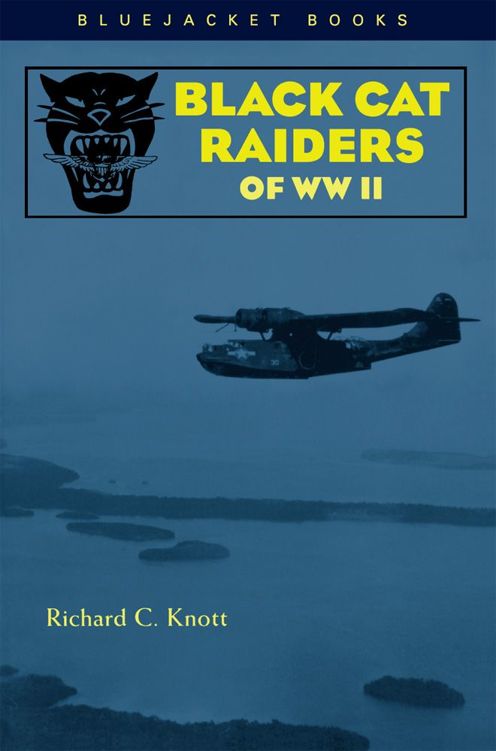

Frontispiece: U.S. Navy photo

To Eleanor

Contents

This is a story of war and vengeance in the South Pacific, of courage in the face of overwhelming odds, and of the unlikely phoenix bird that rose from the ashes of defeat to repay its tormentorsin spades. The story is true, pieced together from a variety of sources including war diaries, squadron histories, reports of action against the enemy, message traffic, official and personal correspondence, and other documents. The names used are those of real persons, many of whom are still living and some of whom have contributed their recollections to this account.

When the war erupted in 1941, the U.S. Navys PBY flying boats were already obsolescent. The British had named them Catalinas, after the idyllic island off the California coast; the Americans, with their penchant for abbreviating everything, inevitably called them Cats. But they were more like sitting ducks to the Japanese fighter pilots who ruled the air in the Western Pacific during the early months of the war. The Cats were no match for the swift and deadly Zeros, and although they engaged the enemy as best they could, the outcome of these encounters was rarely cause for celebration. Sometimes a battered Cat managed to slip away to fight again, but the grim toll of losses was sobering.

By mid-1942, attention was focused on the fact that the few PBY combat missions which could be called successful had almost invariably been flown at night. This realization led to the idea that turned selected PBY squadrons into deadly hunters. The first step in the transformation was a coat of flat black paint, followed by installation of exhaust flame arresters and by a fundamental change in operating procedure. The Cats would sleep by day and prowl at night. Airborne radar developed by the British enabled them to see in the dark. Their revolutionary new radar capability, coupled with their sinister appearance and nocturnal habits, gave them an almost supernatural aura. The Black Cats soon became legend throughout the Southwest Pacific.

To the Japanese the Cats seemed to appear out of nowhere, pouncing upon fleet units and cargo vessels. Attacks were typically made from 2,000 feet in a shallow dive, with engines throttled back to a whisper. By the time the Cats were detected at masthead level by a startled lookout or an unwary officer of the deck, it was too late.

Of course the initial attack rarely resulted in an immediate kill. More often than not, the Cats were obliged to return to the target more than once. On these subsequent passes a fully alerted enemy was ready with a lethal antiaircraft barrage. The ensuing duels between aircraft and ship were sometimes fierce and bloody. Cats often returned to base riddled by machine gun fire, with gaping holes in their wings.

The Black Cats accounted for the sinking or disabling of several hundred thousand tons of Japanese cargo vessels, troop transports, and warships. Curiously, however, their exploits are not widely known today, except to a few aviation history buffs and those surviving pilots and crewmen who took part in their operations. Although they established for themselves an enviable reputation for skill and daring, their operations were not the kind which ordinarily captured the headlines at home. A typical Black Cat began its mission at dusk from an island base or a tender in some isolated lagoon, spent hours searching for its prey and, finding it, fought its grim battle alone in the dark, aircraft-against-ship to a final conclusion. When morning came, only an oil slick might remain as mute testimony to the struggle.

This book is a tribute to those who kept the faith when hope was lost, and to others who came afterward and blazed a trail of burning ships from the Solomons to the Philippines. It is the saga of the flying felines of World War II who came to be known as The Black Cats.

Black

Cat

Raiders

of WW II

He had been unable to shake that feeling of uneasiness ever since his arrival almost a year before. Like other senior aviators who had survived mans early investigations into the mysteries of powered flight, Pat Bellinger had developed a personal warning system, a kind of sixth sense triggered by seemingly insignificant thingsthe color of engine exhaust smoke, the flutter of a control surface, the changing sounds of air passing through struts and wires. Over the years this extrasensory mechanism had matured and become a part of his everyday life. Now it was again telling him that something was wrong.

With a half-frown he scrutinized the Catalina flying boats that squatted in the fading light like great seabirds come ashore to rest. To the casual eye they looked impressive, to some perhaps even formidable. But the solemn-faced man who stood alone on the parking apron knew their real capabilities and he had deep reservations. They were patrol aircraft, cumbersome and slow, designed primarily for long-range search. But because war has a habit of disregarding such orderly distinctions, they were armed with machine guns and were capable of carrying a respectable load of bombs or torpedoes slung under the wings. In the event of a shooting confrontation, could these middle-aged mammoths really be expected to attack an enemy warship or a fortified installationand survive? Perhaps even more important, could they even defend themselves adequately against modern fighters? And if they could, would there be enough of them, and enough crews to fly them, to meet the challenge he thought might come, perhaps without warning?