Oh, but you should be an artist. I had one with my squadron during the last war, for weeks until we went up the line.

Evelyn Waugh: Brideshead Revisited

There are many people whom I should thank for their help in writing this book. I am particularly grateful to Christianna Clemence, Edward Ardizzones daughter, and his grandson, Tim Ardizzone, for so willingly loaning me correspondence and photographs, as well as being so generous with their time. Mrs Anne Ullmann, the daughter of Eric Ravilious, has also been very supportive and helpful. Vincent Freedman, Barnett Freedmans son, has been most generous, allowing me to make use of the extensive Barnett Freedman archive at Manchester Metropolitan University. Jean-Pierre Gross and his sister Mary West have been very helpful and allowed me to include photographs of their father. Mary West also kindly sent me the letter which Edward Bawden wrote to her with his fond memories of Anthony Gross, written in 1987. My thanks are also due to the Estate of Edward Bawden for permission to quote from the artists letters.

The Special Collections Archivist at Manchester Metropolitan University, Jeremy Parrett, has been extremely helpful in guiding me through the Freedman archive and providing me with a number of photographs. Dr Laura MacCulloch (Curator of British Art, National Museums, Liverpool) has also been a valuable guide. I am also grateful to Sara Bevan at the Imperial War Museum and Colin Simpson, Principal Museums Officer, at the Williamson Gallery, Birkenhead. In addition, I would like to thank the following: Fran Baker, Bruce Beatty, Ronald Blythe, Julie Brown (Towner Gallery, Eastbourne), Ged Clarke, Stephen Courtney (Curator of Photographs, National Museum of the Royal Navy), Betty Elzea, Colin Gale (Archives and Museum, Bethlem Royal Hospital), Hannah Hawksworth (The Royal Watercolour Society), Simon Lawrence (at the Fleece Press), Polly Loxton, Michael MacLeod and Peyton Skipwith.

The following institutions have also been useful in the writing of this book: The British Library, both in London and Boston Spa, Yorkshire, The British Library Sound Archive, The Royal Watercolour Society, The Higgins Art Gallery and Museum, Bedford, the National Museum of the Royal Navy, The Henry Moore Foundation, The Ministry of Defence Art Collection, The Imperial War Museum, The National Archives, Regen-Williamson Art Gallery, Birkenhead, The Walker Gallery, Liverpool, and The Towner Gallery, Eastbourne. I should also like to thank my commissioning editor at The History Press, Jo de Vries, for her enthusiasm for this project.

My wife Vanessa has, as always, been an invaluable and generous confidante in the writing of this book. I am most grateful to her.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. It has not been possible, however, to trace the copyright holders of all the photographs contained in the book and I would be pleased to hear from any copyright holder via the publisher.

Finally, I would like to apologise for any errors I have made in telling this story of my nine war artists. I hope that the great regard I have for them all outweighs any inadvertent mishaps or inaccuracies.

Contents

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix A: |

Appendix B: |

Appendix C: |

Appendix D: |

Appendix E: |

I first learned about the vast treasury of war artists work by the luckiest of chances. I was trying to track down the whereabouts of a painting by R. Vivian Pitchforth which he had completed in the middle of the war. It was of seven white Sunderland flying boats in Plymouth in 1942: it was striking and evocative and yet I knew nothing about Vivian Pitchforth. Then, to my surprise, I found that the original was in the possession of Bendigo Art Gallery in Victoria, Australia. Not in Plymouth. I wanted to know why.

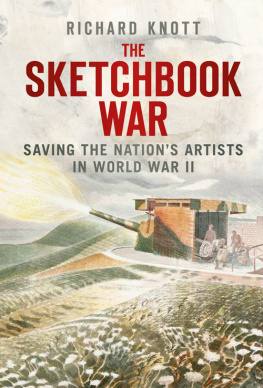

That was the start of it all I became fascinated by the kind of life war artists led, and particularly what it was like for those of them who were nearest to combat. That led me to a whole series of related questions. Who were these artists? Who chose them? How dangerous was such a life? How close to combat did they get? What did the ordinary soldier and airmen think of them? What was it like to sketch in the midst of shellfire and mayhem? Did they carry guns, or simply cling on to pencil and sketchbook? Why did three artists lose their lives? What were they like as men were they set apart somehow, or indistinguishable from those fighting beside them? Later, as I discovered more about the nations war artists, I realised that there was a story to be told about Sir Kenneth Clark of the War Artists Advisory Committee and his flawed plan to keep artists alive during the war, and the extent to which it failed.

In writing The Sketchbook War I have consulted relevant files at the Imperial War Museum, National Archives, Manchester Metropolitan University, Sheffield Local Studies Library and Archive, and the Walker Gallery in Liverpool, as well as the letters of the participants and their published accounts. I spent many hours listening to the taped recordings of interviews conducted with those who survived the war. Held by the Imperial War Museum, they are a wonderful resource and have allowed me to gain a privileged insight into the characters of each of them. Listening to them reminisce in relative old age about the war years proved inspiring somehow hearing the mischief in Edward Ardizzones voice as he uncovers the past, for example, brought me much closer to an understanding of the man himself. It was strange to hear my artists coughing, breaking off for a cigarette, laughing at some prank long ago, drinking tea (tea cups clinking in the background), admitting to fading memory, or struggling with becoming hard of hearing. Such human foibles rendered them even more real than might have been the case with measured prose in a plain journal.

Occasionally, in telling the story, I have allowed myself a certain amount of writers licence, but even those forays into the imaginative hinterland are securely rooted in fact. A valuable additional source of material has been the paintings themselves. At certain points in telling the story, I have turned to the artists paintings and sketches. For example, early in the book there is a description of Henry Moore swimming off the south coast on the day war broke out. That painting 3rd September 1939 I saw at an exhibition at Leeds City Gallery; I was very moved by it the stark coming together of a blue late summers day and the looming blood-filled threat of war and knew that I wanted Moores perspective on that September day to be the first sight of the war the reader gets. Each time a war artist sketched the war as he or she saw it, it added to the pictorial record of those six tragic years. I was grateful too for the way that the sum total of a war artists work, with its sequence of dates and locations, provides a different kind of diary or journal. I liked the way I could read such an account, and follow an artist through their war experience by looking closely at what they had painted, canvas by canvas. I have listed those particular paintings which figure in the text at Appendix C.

1

Next page