Ritual: A system of religious or magical ceremonies or procedures frequently with special forms of words or a special (and secret) vocabulary, and usually associated with important occasions or actions.

Dr J. Dever, Dictionary of Psychology (Penguin Books)

Between February 1965 and July 31st, 1968, the American bombing missions in Vietnam numbered 107,700. The tonnage of bombs and rockets totalled 2,581,876.

Keisingers Continuous Archives

The attitude of the gallant Six Hundred which so aroused Lord Tennysons admiration arose from the fact that the least disposition to ask the reason why was discouraged by tricing the would-be inquirer to the triangle and flogging him into insensibility.

F. J. Veale, Advance to Barbarism (Mitre Press, 1968)

Len Deighton was born in 1929. He worked as a railway clerk before doing his National Service in the RAF as a photographer attached to the Special Investigation Branch.

After his discharge in 1949, he went to art schoolfirst to the St Martins School of Art, and then to the Royal College of Art on a scholarship. It was while working as a waiter in the evenings that he developed an interest in cookerya subject he was later to make his own in an animated strip for the Observer and in two cookery books. He worked for a while as an illustrator in New York and as art director of an advertising agency in London.

Deciding it was time to settle down, Deighton moved to the Dordogne where he started work on his first book, The IPCRESS File. Published in 1962, the book was an immediate success.

Since then his work has gone from strength to strength, varying from espionage novels to war, general fiction and non-fiction. The BBC made Bomber into a daylong radio drama in real time. Deightons history of World War Two, Blood, Tears and Folly, was published to wide acclaimJack Higgins called it an absolute landmark.

As Max Hastings observed, Deighton captured a time and a moodTo those of us who were in our twenties in the 1960s, his books seemed the coolest, funkiest, most sophisticated things wed ever readand his books have now deservedly become classics.

By Len Deighton

FICTION

The IPCRESS File

Horse Under Water

Funeral in Berlin

Billion-Dollar Brain

An Expensive Place to Die

Only When I Larf

Bomber

Declarations of War

Close-Up

Spy Story

Yesterdays Spy

Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Spy

SS-GB

XPD

Goodbye Mickey Mouse

MAMista

City of Gold

Violent Ward

THE SAMSON SERIES

Berlin Game

Mexico Set

London Match

Winter: A Berlin Family 1899-1945

Spy Hook

Spy Line

Spy Sinker

Faith

Hope

Charity

NON-FICTION

Action Cook Book

Fighter: The True Story of the Battle of Britain

Airshipwreck

Basic French Cooking

Blitzkrieg: From the Rise of Hitler to the Fall of Dunkirk

ABC of French Food

Blood, Tears and Folly

Bomber was the first fiction book written using what is now called a lsquo;word processor. In 1969 that name did not exist. It was an IBM engineer visiting my home at the Elephant and Castle in London to check my golfball typewriter, who asked me: lsquo;Do you know how many times your secretary has retyped this chapter? He waved pages in the air.

lsquo;Half a dozen times? I said defensively. I knew my wonderful Australian secretary Ellenor only retyped chapters when her typewritten words were almost obscured by my handwritten changes.

lsquo;Twenty-five times, said the IBM man. lsquo;Your poor secretary!

I tried to look repentant.

Along the street at the mighty Shell Centre, IBM had installed banks of computer-driven machines that produced printed in-house essentials such as instruction manuals.

lsquo;Come along and see them, urged the IBM man. Being somewhat obsessed by machinery (while not really understanding it) I went along. Soon I became the only private individual permitted ownership of an IBM MT 72 computer. It was the size and shape of a small upright piano. I was very proud of that machine, I showed it to everyone who visited me, but it was Ellenor who mastered it.

My friend Julian Symons said I was the only person he knew who actually liked machines. lsquo;Perhaps you should write a book about them, he said, only half seriously. That was the start of Bomber. Does everyone hate machines? Perhaps they do; so suppose I wrote a story in which the machines of one nation battled against the machines of another? It had already happened. I had been bombed quite a lot in London. The night bombing campaigns were fought in complete darkness, with both the enemy aircraft and the terrain below depicted only as tiny blips and blobs on glass screens. The combatants never saw their enemies. It had a spooky fascination for me but would such a grim mechanical theme overshadow a storys human element?

The human element was already a difficult aspect of writing such a story. Most of the charactersboth British and Germanwould be able-bodied young men chosen for their physical, emotional and psychological similarity. To make it more difficult, my preliminary notes showed that I would need a cast of well over a hundred of these similar young people. This meant a style that would bring a character to life in only a sentence or two of dialogue. And do it well enough for the reader to pick up on that character two or three chapters later. And I was determined to do it without resorting to crude regional pronunciations.

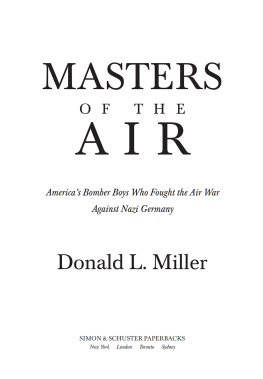

It was daunting. I began to talk to experts and discovered how deep I was going to have to dig for my research. German radar was very advanced by 1943; it was only after that that Anglo American technology took the lead. But Germany lost their technical lead and lost the war too. That meant that very few people had taken any interest in the history of German air defences. I went to Germany and sought out the technicians and radar operators as well as the night-fighter pilots and Flak crews. Then I had to put their explanations together well enough to understand the basis of the German air defence system. The more I studied it, the more the subject fascinated me. Long after Bomber was finished, I wrote Goodbye Mickey Mouse, a totally different sort of book, about the American strategic bombing campaign. The contrast between the social environments astounded me and I needed to wipe this Bomber research from my memory in order to get to grips with the Eighth Air Force.

If 1943 German radar controllers and night-fighter veterans were a complex challenge, then wait until I started to delve into the social life, scandals and Nazi-led politics of a small Westphalian town. Everyone seemed to have a war story. One lady found for me some striped overalls that she had made from her nurses uniform. A man I met in a restaurant had kept all his wartime documents and when I showed interest in them insisted that I kept them. My wife Ysabeles fluent German was the key to this conversational research and greatly expanded the number of people and stories available to me.

It was almost overwhelming but it was too late to stop, and anyway I enjoy research. One large room of my London home was devoted entirely to Bomber. I collected everything available: films, air photos, logbooks, letters, recordings, tele-printer orders and target maps. Pasting aeronautical maps together I covered one whole wall with northern Europe. Tapes of the bomber routes, turning-points, dog-legs and feints showed each aircraft in the story. Tabs for times meant I could see where each fighter or bomber would be at any chosen moment.