I

The Sunbonnet Myth

WHO WAS THE WESTERN woman? What was she like, this gentle yet persistent tamer of the wild land that was the American West?

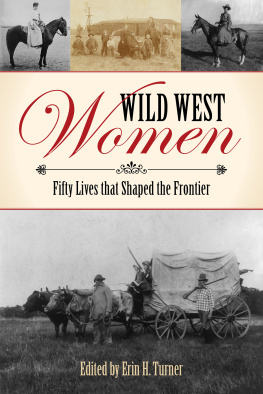

Emerson Hough saw her as a woman in a sunbonnet and saluted her with eloquence: The chief figure of the American West, the figure of the ages, is not the long-haired, fringed-legging man riding a rawboned pony, but the gaunt and sad-faced woman sitting on the front seat of the wagon, following her lord where he might lead, her face hidden in the same ragged sunbonnet which had crossed the Appalachians and the Missouri long before. That was America, my brethren! There was the seed of Americas wealth. There was the great romance of all Americathe woman in the sunbonnet; and not, after all, the hero with the rifle across his saddle horn. Who has written her story? Who has painted her picture?

Other evidence supports this stereotype of the woman in the sunbonnet. In a letter written from Kansas in 1857, Julia Lovejoy described such a traveler riding on the high seat of an ox-drawn wagon with household goods packed all around and above her head, a basket of potatoes to rest her feet upon, in her arms a child not quite two years old, in one hand an umbrella to screen her throbbing head from the oppressive

But the western woman was more by far than a face hidden in a ragged sunbonnet. Often her bonnet was gay with color and ornamented with flowers; sometimes she wore French millinery, the latest styles from Paris, small round hats contrasting with the enormity of her voluminous built-out skirts. Her petticoats were rainbow-colored. Her feet might be shod in rough work clods, but more than likely they were in high boots of finest kid, or high button shoes.

Whatever her dress, she had endurance, she had courage, sometimes she was wilder than the land she tamed.

Why did she venture there, into that vast and violent world of plains, mountains and sky, where danger and death waitedmocking her womanhood, crouching always outside the rings of her campfires, even at her hearthside?

Who was she, what was her name?

It might be Josephine Meeker, twenty-year-old Oberlin College graduate, who wanted to educate the Colorado Indians but was captured by a Ute who taught her the facts of life and then fell in love with her.

Or Frances Grummond, the sheltered Tennessee girl who married a Yankee soldier and learned to cook for him in the wilds of Wyoming; her heart was broken when he died in the Fetterman Massacre.

Or Margaret Irvin Carrington, who tried to soothe the grief of Frances Grummond, never dreaming that within a short time this young southern girl would be married to her own husband.

And thirteen-year-old Virginia Reed, her young mother Margaret Reed, and Grandmother Keyesall of Springfield, Illinoiswho started to California one fine spring morning with twenty-nine others, including two brothers named Donner.

Esther Morris, a dignified lady of fifty-five, whose famous tea party in South Pass City, Wyoming, set in motion the machinery that brought women the right to vote for the first time anywhere on earth.

Julia Bulette of Virginia City, the prototype of all the fancy women in western literature, who wore sable muffs and silk scarves and would have blushed if any man ever caught her wearing a ragged sunbonnet.

Elizabeth Farnham, who sometimes wore bloomers; she tried to organize a party of New York women to journey to the California gold fields for the good of the female-starved miners.

And Flora Pearson Engle, who did join an expedition of prospective brides for Washington Territorys lonely bachelors and proudly told her story.

Eliza Hart Spalding and Narcissa Whitman, two gentle missionaries who rode sidesaddle most of the way from Independence, Missouri, to Oregon; they would have appreciated riding in the front seat of a covered wagon but they would not have worn ragged sunbonnets.

Dame Shirley, a gay young bride in the California gold rush, who read Shakespeare and Shelley and was amused by the hell-roaring life surrounding her.

Jane Barnes, a blond barmaid of Portsmouth, England, who traveled all the way to Astoria in Oregon with a gentleman friend and was the first white woman to set foot on the Northwest coast. Her fine bonnets so impressed a Chinook chieftain that he proposed marriage.

Elizabeth Custer, one half of a mutual admiration society consisting of herself and husband Georgewho died at the Little Big Horn.

Martha Summerhayes, who followed her Army husband into the wilds of Apache-ridden Arizona; both of them managed to survive.

And another Army follower, Annie Blanche Sokalski. She wore wolfskin riding habits, traveled with thirteen hunting dogs, and counseled her husband during his court-martial at Fort Kearney.

Ann Eliza Young, one of Brighams wives, a female subversive among the Saints.

Janette Riker, who lived through a Montana winter alone in a covered wagon.

Lotta Crabtree, actress, adored by every western male; she smoked cigarets and showed her legs but still convinced her admirers that it was all in a spirit of childish innocence.

Susan Shelby Magoffin, the first white woman to travel the Santa Fe Trail. She did it in style, with silk sheets, counterpanes, a dressing bureau, and a maid. She was the antithesis of the gaunt-faced woman in the sunbonnet.

Loreta Janeta Velasquez, who fought through the Civil War disguised as a male, then went west dressed in frilly furbelows to catch herself a husband. She did, a rich one.

But most of their names are now forgotten, with only brief fragments of their lives preserved in a simple diary, a letter home, a notice in a contemporary newspaper. Schoolmarms, loving wives, eligible daughters, hopeful old maids, camp followers, adventuresses, missionaries, suffragettes, travel-book authoresses, actresses, reformers, calico cats.

They traveled westward not only in covered wagons but on river boats, in army ambulances, in jolting railway cars, aboard sailing ships to Panama and by muleback across the Isthmus, or around Cape Horn to San Francisco, and some of them even walked, pushing handcarts before them.

The impulses that moved them were as diverse as the women themselves. Said the wife of a Pennsylvania carpenter who had pulled up stakes and headed toward the setting sun: Oh, we had heard of the west, where everyone is sure to get rich, and so we came. Susanna Moodie put the answer even more frankly: By what stern necessity were we driven forth to seek a new home amid the western wilds? We were not compelled to emigrate. Bound to England by a thousand holy and endearing ties, surrounded by a circle of chosen friends, and happy in each others love, we possessed all that the world can bestow of goodsbut