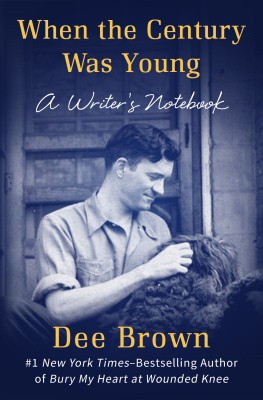

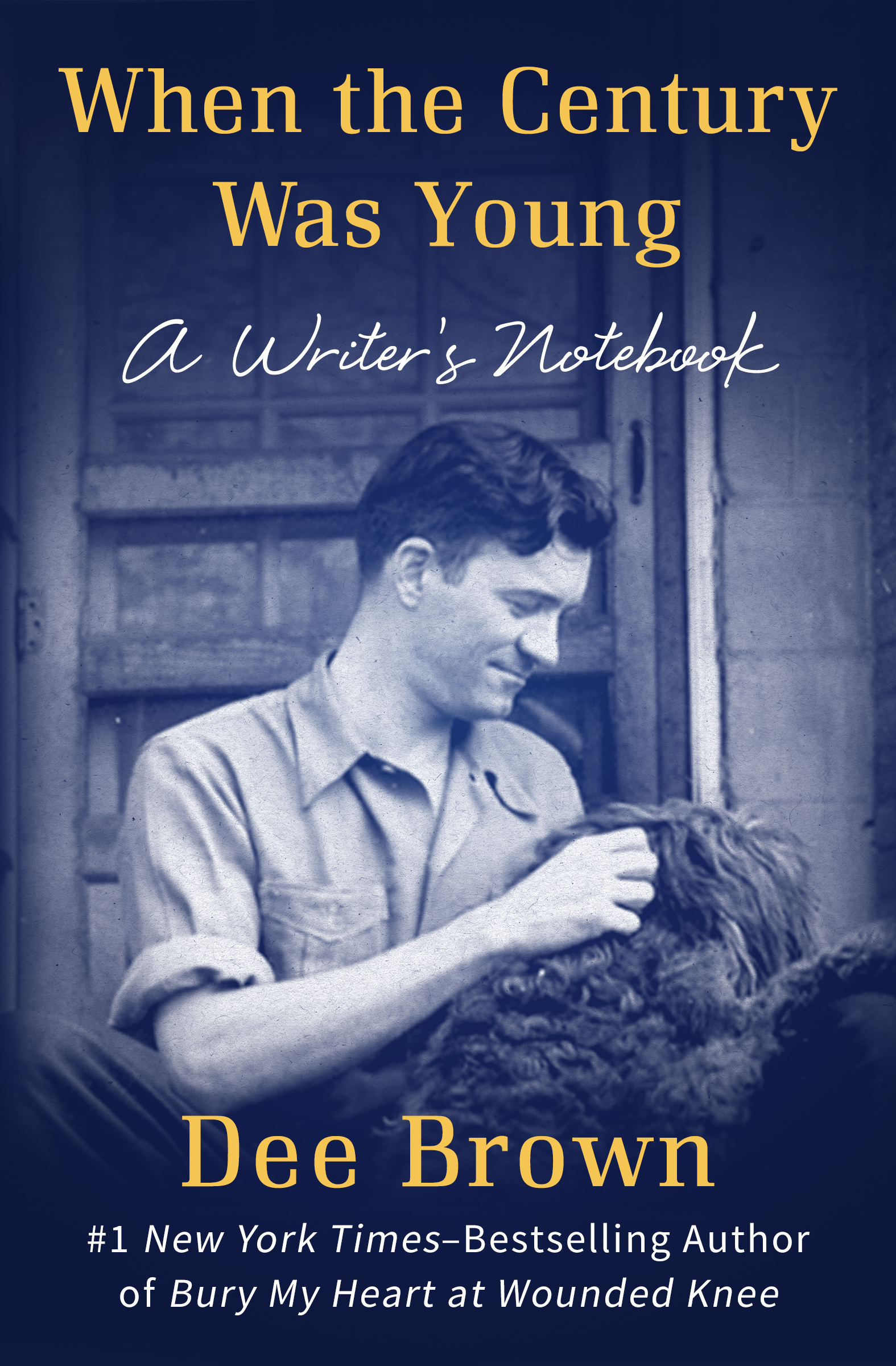

When the Century Was Young

A Writers Notebook

Dee Brown

In memory of

Robert B. Downs, mentor and friend

Daniel Alexander Brown, about 1907

CHAPTER ONE

Discovering the World of Print

THE EARLY PART OF this century was the golden age of print, and I was born into it. Newspapers, magazines, and booksin that orderwere the major sources of information and entertainment. Radio and television came later as interloping marvels, but even to this day the electronic devices do not match the authority of print.

One of my few memories of my father, Daniel Alexander Brown, who was killed when I was four, is of his reading to me the Sunday comics in the Shreveport Times while I sat in his lap looking at the cartoon figures held in front of me. One of the contemporary strips had a character named Buster Brown, and I assumed that Buster was a relative among all the numerous Brown kinfolk in the Bienville Lumber Companys sawmill town of Alberta, Bienville Parish, Louisiana.

The world that I was born into bore little resemblance to the world we live in today. It was so close to the nineteenth century that I have always felt a kinship with that era, which was then very slowly beginning to disappear. I remember these: horse-drawn carriages, button shoes, corsets and feathered hats for women, maypoles in the schoolyards in springtime, quiet orderly schoolrooms, five-cent soda pop and snack foods, mule-drawn wagons and plows, quilting bees, spelling bees, magic lanterns, kinetoscopes, and silent movies. Mark Twain died when I was two, but as a youth I was very much aware of the unseen yet living presences of Buffalo Bill Cody, Thomas Edison, Teddy Roosevelt, President Woodrow Wilson, Henry Ford, Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany, Mrs. George Armstrong Custer, and real cowboys and Indians, including Hollow-Horn Bear, the Sioux chief whose face appeared on a postage stamp after his death.

Included in my natural environment were steam locomotives, Civil War veterans reunions, Victorian attitudes, genuine patriotism, baseball players who loved the game as well as money, efficient railroads and trolleys, long flannel underwear, inexpensive books, gadgets that were easily repaired and were usable for years, Model-T Fords, frequent and sudden fatal diseases, depressing funerals held in family parlors, hellfire-and-damnation sermons, religious revivals under big tents, and politicians who apparently believed in honor and country. Some of these things were splendid; others struck terror, especially in the hearts of the young.

I was five when my widowed mother, Lula Cranford Brown, moved us from Louisiana to the town of Stephens in Ouachita County, Arkansasthe southwestern coastal plain, as geographers map that area. We traveled there by railway train, a journey that I but dimly remember. I do recall vividly, however, our arrival at the house where we would live through the next decade into my middle teens. Perhaps the occasion was impressed upon me by the number of adultsmy mothers two sisters, their husbands, and others whose identities I do not recallwho met us at the railway station. They made numerous comments about the house and its grounds while we were approaching the place. As the adults and my sister, Corinne, and I came walking up a grassy slope to a wooden gate in a wire fence, we were greeted by a flood of blossoms at our feet, hundreds of bright multicolored phlox in total disorder. Seed had been washed through the fence onto a small sandy-clay delta created by run-off from spring rains. Through the fence we could see similar but not so lush flowers in broken borders on each side of a red-brick sidewalk inside the untended yard.

As we entered through the gate, one of the menan uncle probablypointed out a large fig bush far to the right, and a tall chinaberry in the left corner. Both were in full leaf. Then one of my mothers sisters said something about a fire-blackened hollow stump no more than a foot high a few yards to our left. She called attention to the evidences of past attempts to burn and uproot it from the earth. The black stump would play a symbolic role from time to time throughout the years we lived there.

The house had been built and lived in for a short time by relativesthe H.P. Morgans. The wife had recurrent dreams of pots of gold being found under a sweetgum tree in the front yard. The dreams were so vivid that the wife persuaded the husband to cut the tree down and dig under its roots. She had died before all of the stump was burned and removed, although workmen had dug all around it. In his grief the husband refused to continue living in the house and sold it to my mother.

The morning of our arrival we entered the house by climbing L-shaped steps built of heavy boards to an L-shaped front porch, both wings of which were quite deep and wide. The door on the right was of solid dark-stained wood; it opened into the parlor room. The screen door on the left entered a wide hallway that divided the house. On the left were two bedrooms. On the right were two more bedrooms leading to a dining room, kitchen, and large pantry. The hallway itself led out to a back porch, at the far end of which was a well made of circular tile about three feet in diameter. Straight ahead from the well through a high gate was a smokehouse and a barn.

This was the setting, the arena in which I spent my youth, the formative years that psychologists dote upon. The milieu was town and country mingled. We lived on the edge of a village that I walked through almost every day. Each resident in the community was magnified because there was a limited number of them. Each person, each name, was important. And for three or four miles around, the fields and creeks and fragrant pine forest, as well as the inhabiting animals, domestic and wild, were free for my seeing.

It was here that I became a consumer in the world of print. Words on paper fascinated me more than spoken words. One person in particular was responsible for this, I believemy maternal grandmother, Ann Elizabeth Cranford. She came to live with us soon after we moved into the house and my mother went to work in a local dry goods store. Although Grandmother Cranford was nearing eighty (and would live to be 101), she seemed never more than half her age physically, and her inquiring mind was interested in everything under the sun.

She had a fund of stories about her experienceschildhood in Tennessee (her father hunted with Davy Crockett), the covered-wagon trek to southwest Arkansas in 1849 (this was the year of the gold rush, but they liked Arkansas well enough that they decided not to go on to California), the Civil War in which she lost two brothers (at Shiloh and Stones River), General Steeles Yankee invaders in Ouachita County (Wild Bill Hickok was said to be one of their scouts who was captured in Camden), her cavalryman husbands capture in Tennessee and imprisonment at Rock Island, Illinois (he returned home mysteriously wearing parts of a Union Army uniform). Her husband, Henry Griffin Cranford, died when I was two years old, and my only memory of him is of a painted portrait that hung on the wall above my grandmothers bed.

Next page