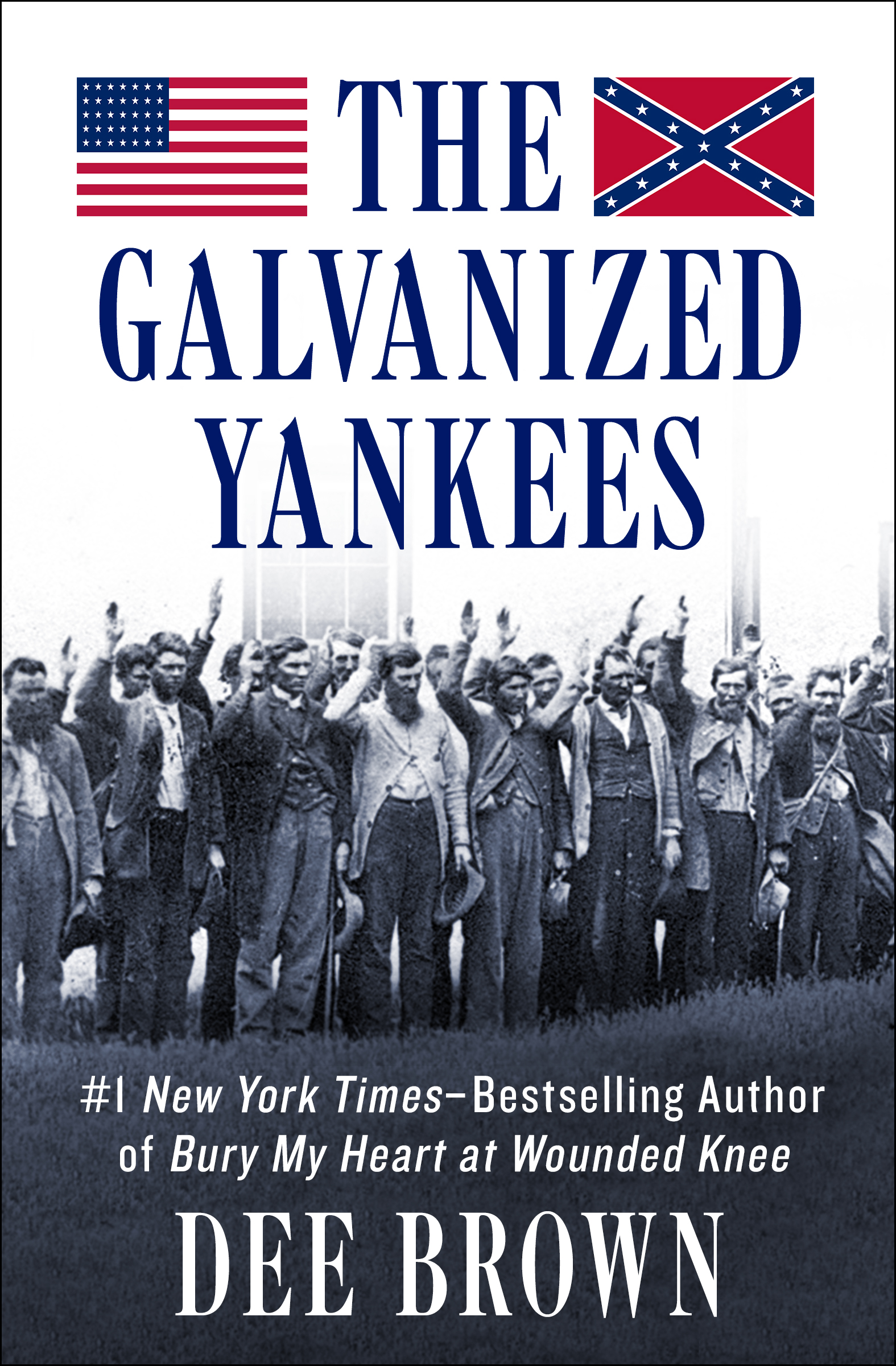

The Galvanized Yankees

Dee Brown

I

Introduction

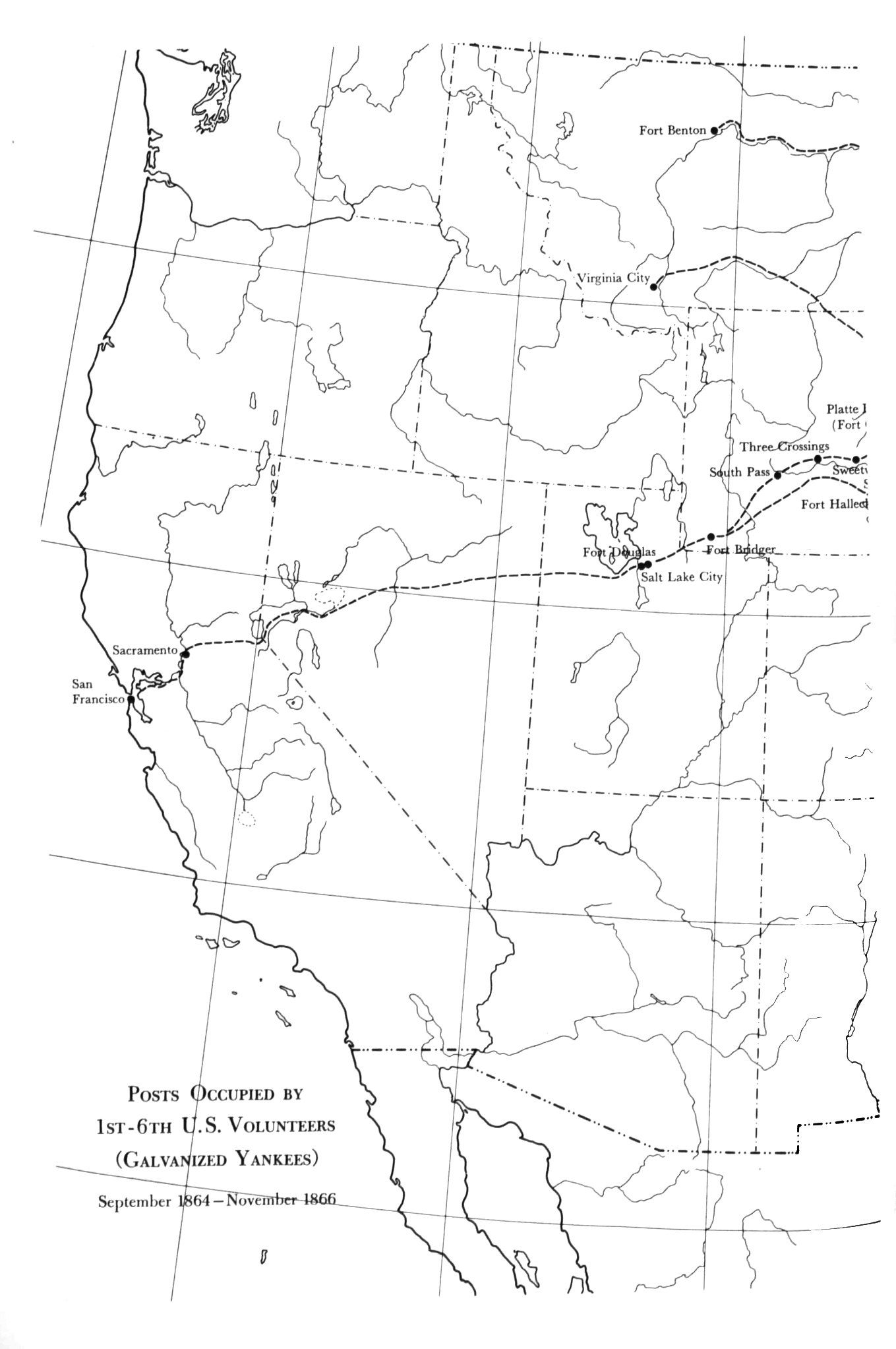

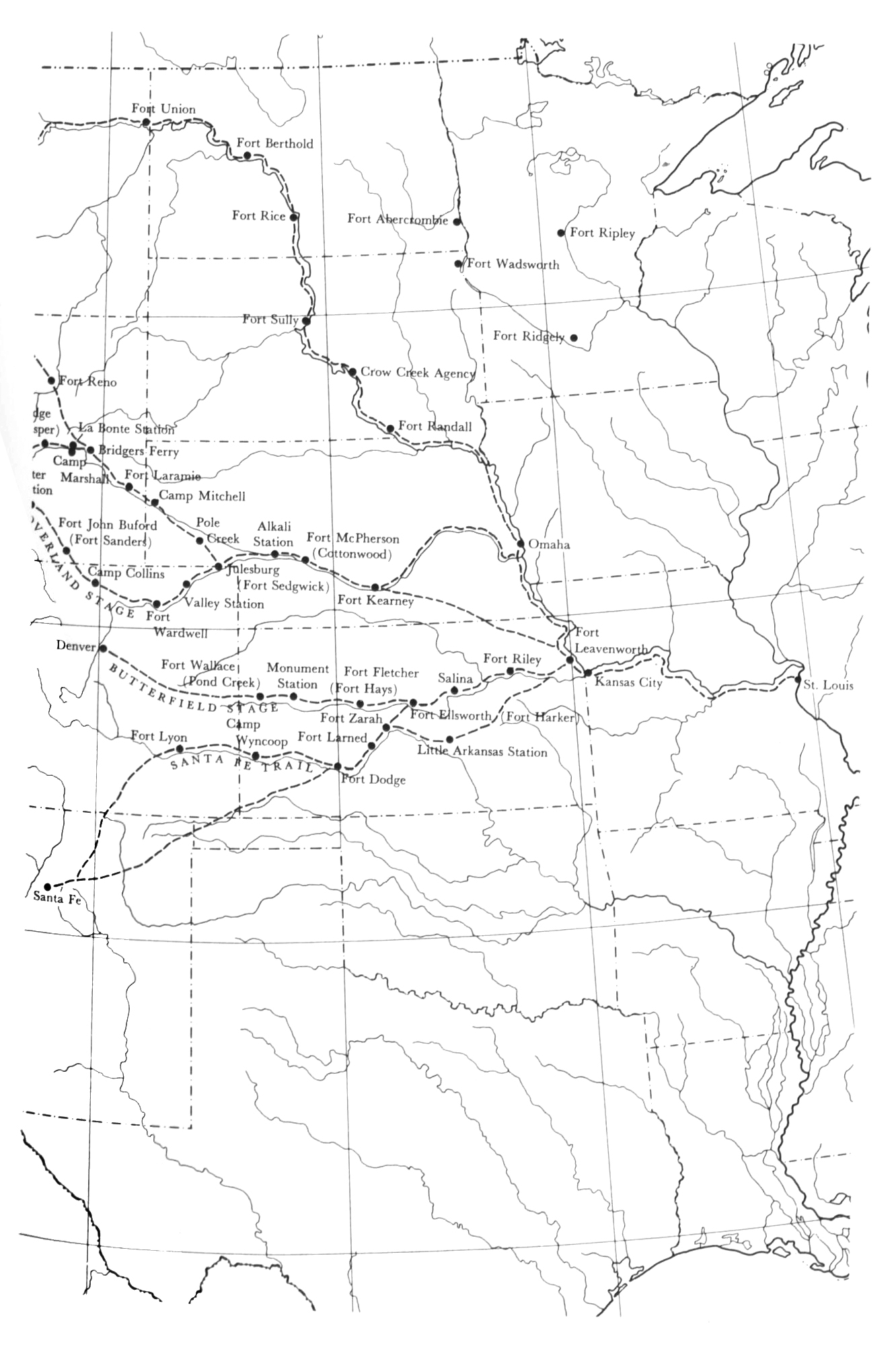

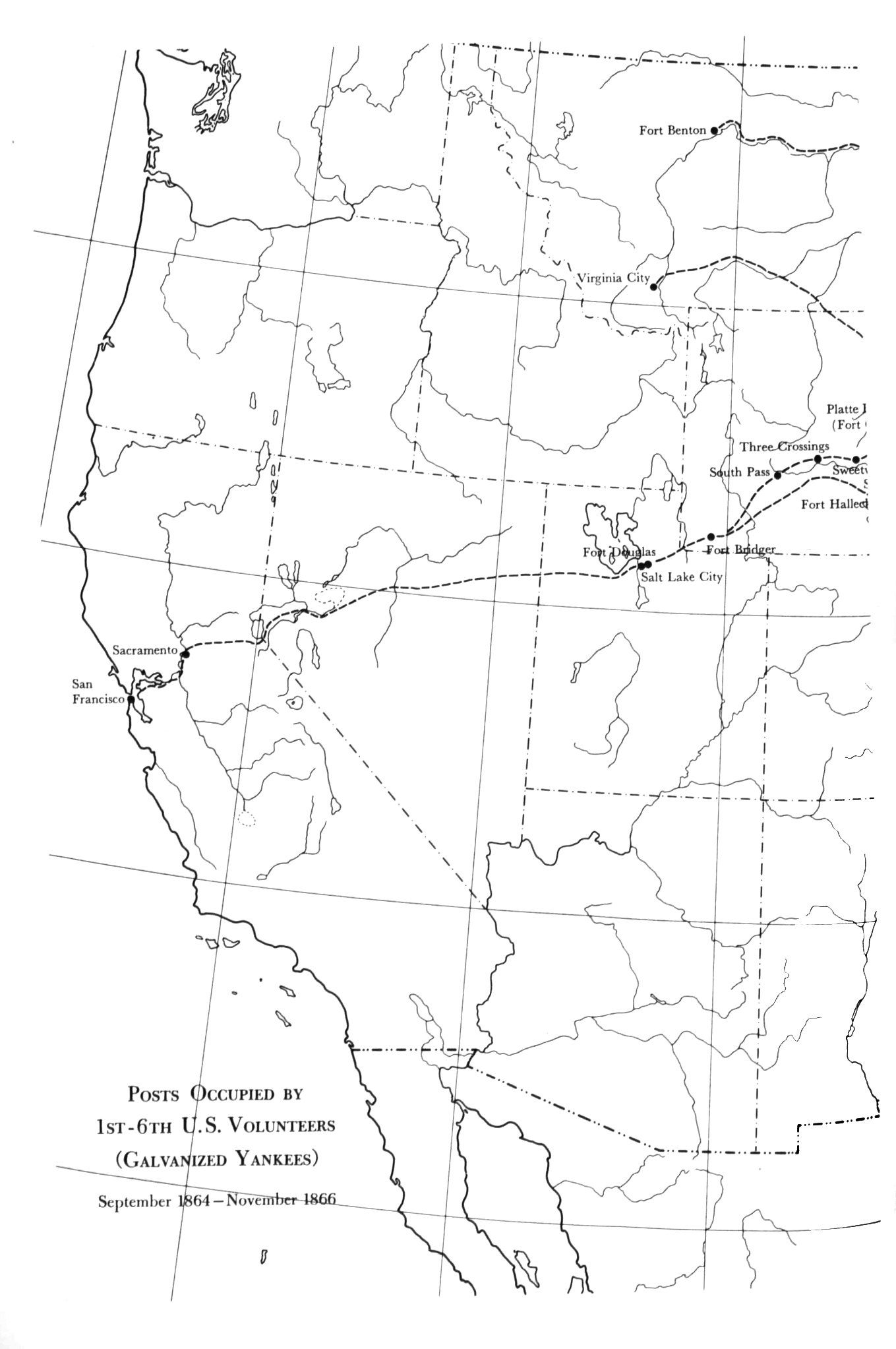

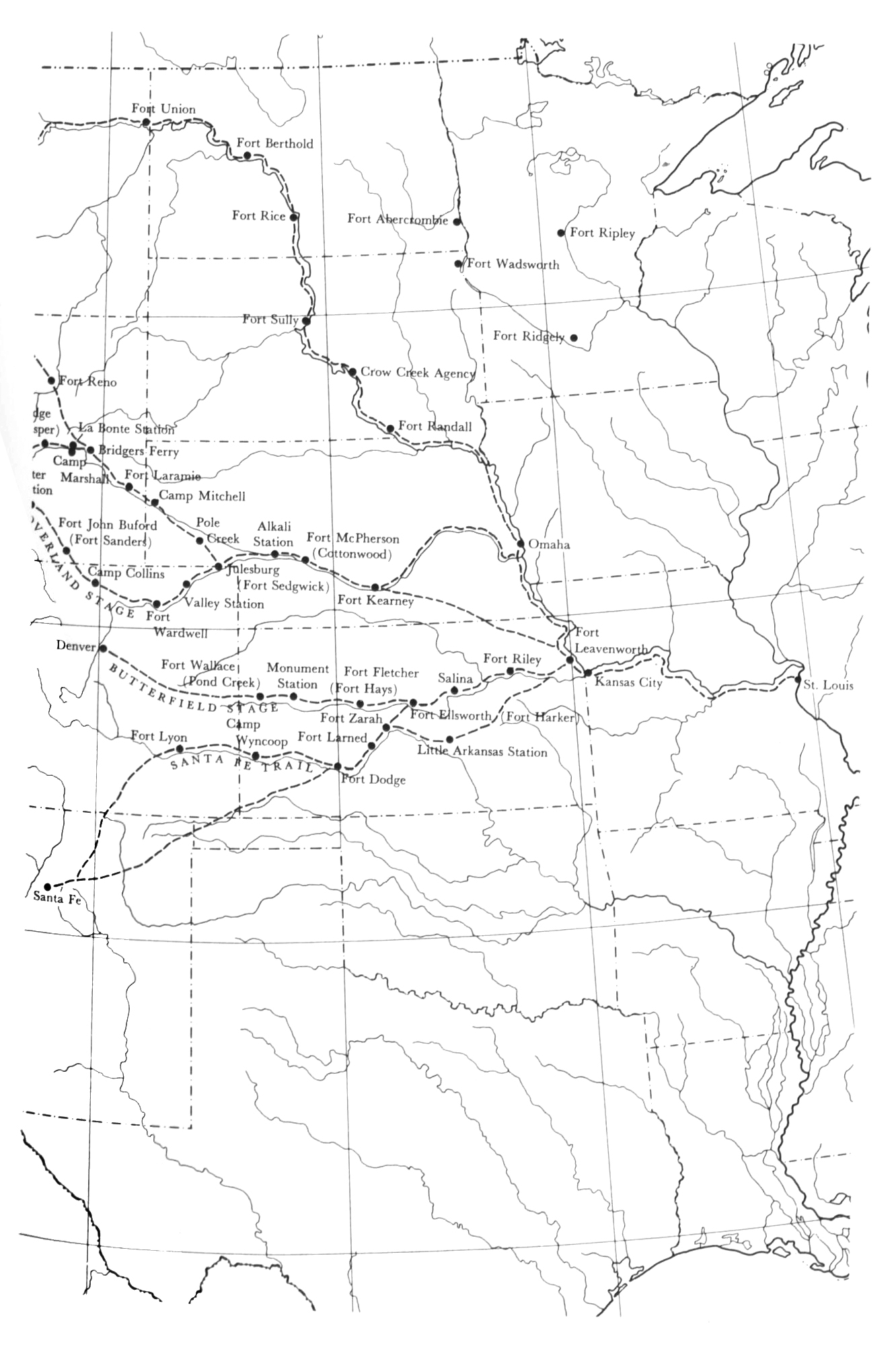

FROM THE CANNON BALL River in Dakota up the muddy Missouri to Montana; along the Platte, the Sweetwater, the Powder, and other watercourses of the Great Plains and the Rockies; on the Oregon Trail and the Santa Fe Trail; out through South Pass and the Wasatch Mountains to the Salt Lake country of the Mormons; in camps and cantonments and a score or more fortsKearney, Rice, Reno, Union, Laramie, Bridger; at ranche stops of the Overland Stage; in cedar-and-adobe huts of the Pacific Telegraph Line; everywhere on the Western frontier in those last days of the Civil War and the hard months after it ended, some 6,000 Americans served as outpost guardians for the nation that at one time or another each had sought to destroy.

These were the Galvanized Yankees, former soldiers of the Confederate States of America, who had worn gray or butternut before they accepted the blue uniform of the United States Army in exchange for freedom from prison pens where many of them had endured much of the war. Sent to the Western frontier so they would not meet their former comrades in battle, they soon found a new foe, the Plains Indian.

Between September 1864 and November 1866 they soldiered across the West. Many of them died therekilled by Indians, scurvy, epidemic disease, wintry blizzards. Some of them deserted,

Officially they were known as the United States Volunteers, six regiments recruited from prisons at Point Lookout, Rock Island, Alton, Camps Douglas, Chase, and Morton. Some were foreign-born, Irish and German predominating; some were native stock from the hill country of Tennessee, North Carolina, and Kentucky; a few were from the Old South plantation country, from Virginia to Louisiana. Each man had his own reasons for choosing this dubious route to freedomdesperation from dreary months of ignominious confinement, of watching comrades die by the hundreds in prison hospitals; a determination to survive by any means; disillusionment with the war; a genuine change of loyalty that was as emotional as religious conversion; a secret avowal to desert at the first opportunity; despair, optimism, perhaps cowardice. In that day there were no psychologists to interview these 6,000 Galvanized Yankees, to search their minds and record their inner fears and longings.

After a century they have been almost forgotten. At the end of service they were discharged at Forts Leavenworth and Kearney. They scattered with the winds, some choosing new names, new identities. In the Old West a mans past was his own business. It was the man who mattered, not what he had been.

One may conjecture upon their peacetime pursuits: solid citizens and gunfighters, cattlemen and rustler, miners and highwaymen. The glories of the Civil and Indian wars were kept alive by local organizations, which held annual reunions for half a century or more, recounting personal feats of bravery, recording them for posterity. If the Galvanized Yankees met in reunions, they must have gathered anonymously. Few of them indulged in reminiscences. No Southern state would claim them; the Grand Army of the Republic forgot them. They were a lost legion, unhonored, unsung.

Yet the record of the six regiments in the West is one in which any American could take pride. During the spring and summer of 1865, the 2nd and 3rd Regiments restored stage and mail service between the Missouri River and California, continually fighting off raiding Indians. They escorted supply trains along the Oregon and Santa Fe trails; they rebuilt hundreds of miles of telegraph line destroyed by Indians between Fort Kearney and Salt Lake City. They guarded the lonely dangerous stations of the telegraphers. In the autumn of 1865 and through most of 1866, the 5th and 6th Regiments assumed these same dangerous duties. Sometimes they carried the mail through themselves. Two companies of the 5th escorted Colonel James Sawyers Wagon Road Expedition to Montana, and then served for almost a year as rearguard outposts at isolated Fort Reno. Six companies of the 6th Regiment were strung out across 500 miles of trails between Fort Kearney and Salt Lake City.

On the bitterly contested Minnesota frontier, the 1st Regiment helped keep hostile Sioux off the settlements; along the Missouri River the 1st and 4th Regiments manned five forts, were engaged in numerous skirmishes, fought gallantly in one bloody battle. In the autumn of 1865, four companies of the 1st marched out upon the Kansas plains to open a new stage route, and endured a winter of Indian attacks, starvation, and blizzard marches.

There were Galvanized Yankees in Patrick Connors Powder River Expedition; they fought on the Little Blue, the Sweetwater, at Midway, Fort Dodge, Platte Bridge. They guarded surveying parties for the Union Pacific Railroad; they searched for white women captured by hostile Indians. They knew Jim Bridger, Wild Bill Hickok, Buffalo Bill Cody, Spotted Tail, and Red Cloud, before the outside world had scarcely heard these now celebrated names. In the course of their military duties they found time to write poetry, to publish a newspaper. And at least one Galvanized Yankee achieved legendary fame in later lifeHenry M. Stanley, who found Dr. Livingstone in Africa.

They went West in a time of great urgency. Thousands of Union soldiers were nearing the ends of their three-year voluntary enlistments, and draft calls were causing riots in Northern cities. Peace groups and Copperheads were inciting sedition and sabotage. A Presidential campaign was dividing the Unions purposes. Prices were soaring and morale was falling on the home front. Danger threatened from Canada, where small bands of Confederates plotted invasion. In Mexico, European adventurers were gathering around the French emperor, Maximilian, with dreams of severing the rich Western states and territories from a weakened United States.

Aware of dwindling forces in frontier forts, hostile Indian tribes had begun raiding as early as 1862, and by 1864 a full-scale Indian war was sweeping the Plains. Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, Colorado, and Minnesota were thinly populated, and many of their young men had gone East to fight for the Union. Regiments were recalled, yet local territories could not supply enough troops to staff forts necessary for security, or to guard the long lines of sustenance and communication which held East and West together.

In mid-year of 1864, Fort Kearney on the Oregon Trail could muster only 125 men; Fort Laramie 90. Thirty-nine men held Fort Larned on the Santa Fe Trail. In late summer of that year the Overland Route was completely closed for a month; not a stagecoach or a wagon rolled; no telegraph messages could be sent over broken lines. Californians were cut off from the Eastern United States, except by sea passage around the Horn or over the Isthmus. Supplies, mail, and news for Coloradans had to come by boat to San Francisco and then overland from there.

Old-timers often described 1865 as the bloody year on the Plains, and that was the year the Galvanized Yankees fanned out from the armys staging point at Fort Leavenworth along Western trails and rivers, to do their share of what had to be done. In personal and public records of that time and place, one can find frequent references to their presence.

Next page