University of Virginia Press

2013 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2013

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Dehler, Gregory J., 1968

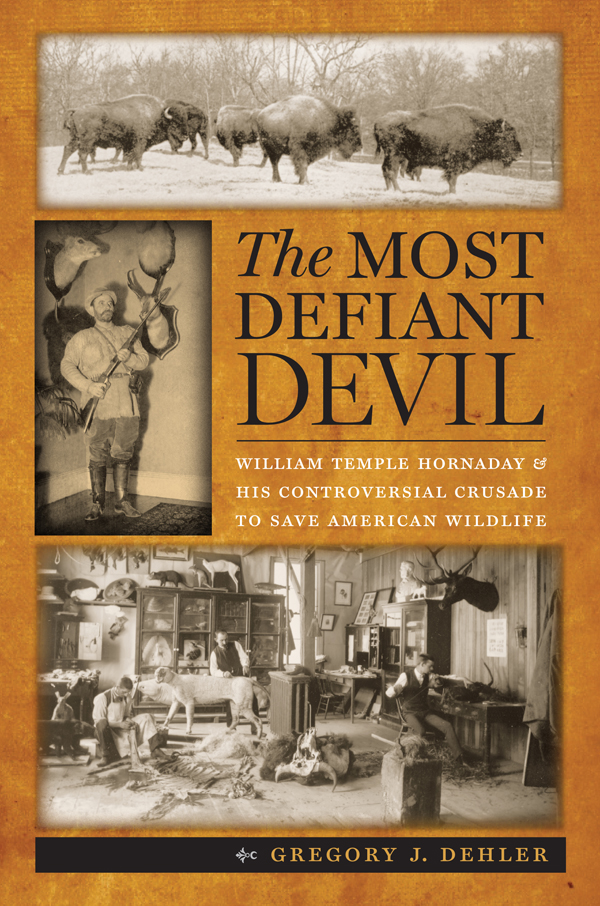

The most defiant devil : William Temple Hornaday and his controversial crusade to save American wildlife / Gregory J. Dehler.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8139-3410-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8139-3434-1 (e-book)

1. Hornaday, William T. (William Temple), 18541937. 2. NaturalistsUnited StatesBiography. 3. ZoologistsUnited StatesBiography. 4. Wildlife conservationistsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

QL 31. H 67 D 44 2013

590.92dc23

[B]

2012046590

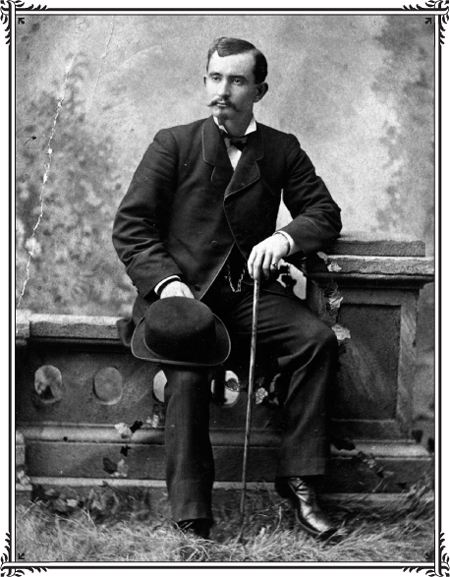

Title page illustration: William Temple Hornaday around the time of his return from his collecting expedition to Asia in 1879. Courtesy of the Guilford Township Historical Collection, PlainfieldGuilford Township Public Library.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book started nearly twenty years ago when I walked into Dr. Richard Harmonds office at St. Johns University and asked him for advice on a masters thesis topic covering the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. He rattled off three names: Speaker of the House Joseph Cannon, the author Thornton Burgess, and the conservationist William Temple Hornaday. I selected Hornaday for the most pragmatic reason: The Bronx Zoo, which was a short drive from my home on Long Island, possessed the bulk of his professional papers.

A project this long incurs many debts, and I would be remiss if I did not thank all those who assisted me in one form or another. I wish to thank Dr. Harmond for placing me, however unwittingly, on the path of a truly captivating, if at times maddening, subject; Steven Johnson, former librarian at the Wildlife Conservation Society, who provided great help with Hornadays enormous bulk of material; Tom Wells, Kurkpatrick Dorsey, Susan Murray, and the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable suggestions that directly shaped the final product; Christie Lowrance for our discussions of Hornaday and Burgess; Steven Hornaday for helping with his (and William Temples) interesting family history; the late Peter Edge for taking the time to talk to me in 1999 and for sharing his mothers unpublished autobiography; Stephen Haynes of Minneapolis, Minnesota, executor, Estate of Emily J. (Bates) Haynes and owner of the papers of Chester E. Jackson, who contacted me out of the blue and shared his great-grandfathers valuable collection; Boyd Zenner and the staff of the University of Virginia Press; and all the librarians and archivists who over the years answered queries, sent photocopies, and offered suggestions. I especially want to thank Dr. Stephen Cutcliffe of Lehigh University. He is a patient editor, a good friend, and a model mentor.

Finally, I could not have completed this book without the encouragement and assistance of my family. I am truly grateful to have had parents who valued education and supported me in every way possible. My wife and our two children have demonstrated remarkable forbearance and patience as I buried myself in my office all too often to write the life of William Temple Hornaday.

INTRODUCTION

I repeat, and urge you to remember the fact that I am not a repentant sinner in regard to my previous career as a killer and preserver of wild animals, but I am positively the most defiant devil that ever came to town. I am ready and anxious to match records for my whole 76 years with any sportsman who wishes to back his record against mine for square dealing with wild animals.

WILLIAM TEMPLE HORNADAY TO ROSALIE EDGE , 11 NOVEMBER 1931

THE YEARS 1800 to 1900 were a bloody century for American wildlife. Prolific species like the ubiquitous passenger pigeon and the hardy buffalo were gunned down with reckless abandon. A determined group of conservationists managed to pull the buffalo back from the brink of extinction, but the passenger pigeon fell into the abyss. In 1914, Martha, a passenger pigeon who was the lone survivor of a species that may have numbered as many as 5 billion when Columbus landed, died in a Cincinnati zoo.

Various local extinctions mirrored the national exterminations of the buffalo and passenger pigeon. Throughout the country, antelope, deer, elk, turkey, and quail were just some of the species completely driven from the townships, counties, and states they had once inhabited.

In a burgeoning national economy, the railroad supplied wildlife products to the rapidly growing urban marketplaces. The buffalo provided

This slaughter did not proceed without protest, however. Increasingly in the late nineteenth century, people voiced opposition to the killing of American wildlife. Among those speaking out were gentleman sportsmen hunters who decried market hunting; scientists who disparaged the wasteful use of resources and sought to rationalize the killing; Audubon Society women who valued songbirds; and hikers and mountain climbers who formed organizations like the Sierra Club in California to protect their wilderness retreats. The protesters also included urbanites who desired to escape their overstimulating environments, bird-watchers devoted to species of no economic value, and thousands of concerned citizens who voraciously consumed the books of such authors as John Burroughs, Jack London, John Muir, Ernest Thompson Seton, and Mabel Osgood Wright in the comfort of their urban parlors.

This eclectic group was united by a common perception that nature was a collective commodity. Their outlook was a clear expression of the Progressive Era ethos of placing the greater good of society before the gains of a few individuals and businesses. Like the larger Progressive reform effort, the conservation movement placed most of the blame for the ills of the land squarely on greed. As the larger Progressive Era reform movement sought to level the playing field through the application of state power to regulate incomes, labor practices, social habits, and the marketplace, conservationists sought to employ the same means to protect the environment. In both cases, they relied on the opinions of established experts to shape policies.

The Progressive conservation movement racked up impressive accomplishments between 1900 and 1920. Its various interests, constituencies, and allies exponentially expanded the forest reserves and placed them under the expert management of the Forest Service, added national parks, enlarged the scope of protection under the Antiquities Act, established numerous bird and wildlife sanctuaries and refuges, and put hunting laws on the books. They also returned the buffalo to the prairie, created protections for all migratory birds, brokered treaties to conserve resources across international boundaries, and developed a national conservation policy. In the process, conservationists dramatically increased the role of the federal government in areas traditionally reserved for the states.