The Adventure Begins

Two rifle shots rang out along the shore. An enormous crocodile, wounded, angry, and deadly dangerous, made its way across a sandbar to the edge of the Orinoco River. Not far away, two hunters stood watching the beast they had been attempting to kill. The hunters were Chester Jackson and William Temple Hornaday.

The injured animal was halfway across the sandbar when young Hornaday suddenly dropped his weapon and began to run after it. He hoped to head it off before it vanished into the water.

You fool, Bill! Dont go near him! Chet shouted, frantically working an empty shell out of his rifle where it had stuck fast.

Ignoring his friends warning, Hornaday caught up with the fleeing crocodile. Bring my rifle, quick! he called, trying to get behind the animal to grab its tail. Just then, it turned swiftly around and lifted its head high above the sand. Its jaws gaped open, its double row of terrifying teeth only a foot away from the young hunter.

Chet answered angrily. You young fool! Get away from there! By then his rifle was ready for action. One more bullet went crashing into the neck of the crocodile. And in a matter of minutes the once-dangerous beast was dead.

What in the name of heaven were you thinking about anyway? Chet asked, still angry. You could have held a train of cars as easily as him. I thought he was going to grab you up and run into the water with you!

I just wanted to keep him busy and keep his mind off the water while you came up and finished him, Hornaday replied in a shaky voice. Come on, lets get that tough hide off him, just to change the subject.

Soon the two men were absorbed in the painstaking task of skinning the crocodile.

Twenty years old, Bill Hornaday had come to the jungles of Venezuela to kill wild animals. His mission was to bring their skins and skeletons back to Rochester, New York, where he was employed at Wards Natural Science Establishment. There they would be mounted for display and sold to museums all over the country. If his expedition was successful and he returned to Rochester with a good supply of jungle beasts, perhaps Professor Ward would finally consent to the East Indies trip that he had been trying to wangle. Even as a boy on his fathers farm, he had dreamed of those distant dark green jungles. As much as he was enjoying his present adventure, he could not help wishing he had been able to talk Professor Ward into that other trip instead.

He realized, of course, that he had come just about as close to his boyhood dreams as any twenty-year-old might hope. How many others of his age born in Plainfield, Indiana, had managed to have such adventures in South America? None at all, he guessed.

William was born in December, 1854, six years before the Civil War. He was the youngest of several sons. His father was a farmer. When he was almost four the family and its flocks and horses outgrew their lovely little farm. Although they knew they would miss the clear streams and blue grass of central Indiana, and their relatives in and about nearby Indianapolis, they decided to move to Iowa to a larger farmstead. They had relatives there, too.

William and his mother and the household belongings were settled in covered wagons. The menhis father, his older brothers, and several hired handsdrove the horses and guided the flocks and herds that followed along behind. It was a typical pioneer wagon train, a familiar sight in those days.

One sunny afternoon their journey took them alongside a branch line of the Chicago and Indianapolis Railroad. Railroad trains, and the wood-burning, smoke-belching locomotives that pulled them, were a much less familiar sight than wagon trains. The little boy had never seen one. Neither had most of the horses.

When they came to a curve in the railroad tracks, they looked north and saw a locomotive with a passenger train rushing, it seemed, right toward them.

Hold those horses! shouted his father, realizing that they were about to bolt in panic. Everyone out! Grab the bridles! Quick! Get out, everybody!

Instantly the wagons halted, and everyone obeyed. William, the littlest pioneer, was right near the railroad fence, next to the lead team of horses. He could hear the awful roar of the locomotive. He was terrified. Nothing in his brief experience of the world had prepared him for this. He looked up and saw a big black monster racing directly at him.

Before his mother knew what was happening, he dashed toward what seemed to him to be a safe place underneath one of the horses. He didnt knowhow could he?that the horses were as frightened as he, and might run at any second. If they did, he would be crushed under the wagon.

He heard his mother scream. William! Someone save William!

One of the farm workers reached under the wagon and snatched the boy to safety. Another held the horses, which even then were stamping, trying to run.

But he learned that the locomotive was not to be feared, that it made a great noise but stayed on its own path. The wagon train reorganized itself and the pioneer trek continued.

The farm in Eddyville, three miles south of the Des Moines River, was a wonderful place for a boy to grow up. He had chores to do, of course; and he got some schooling. But mostly he could watch the changing seasons, the wild roses when they came, and the virgin Iowa prairie. He chased the prairie chickens, quail, ground squirrels, pocket gophers, and hundreds of kinds of prairie birds. When the family went back to visit their relatives living along Eagle Creek in Indiana there were different animals to become acquainted withturtles, yellow perch, little green herons.

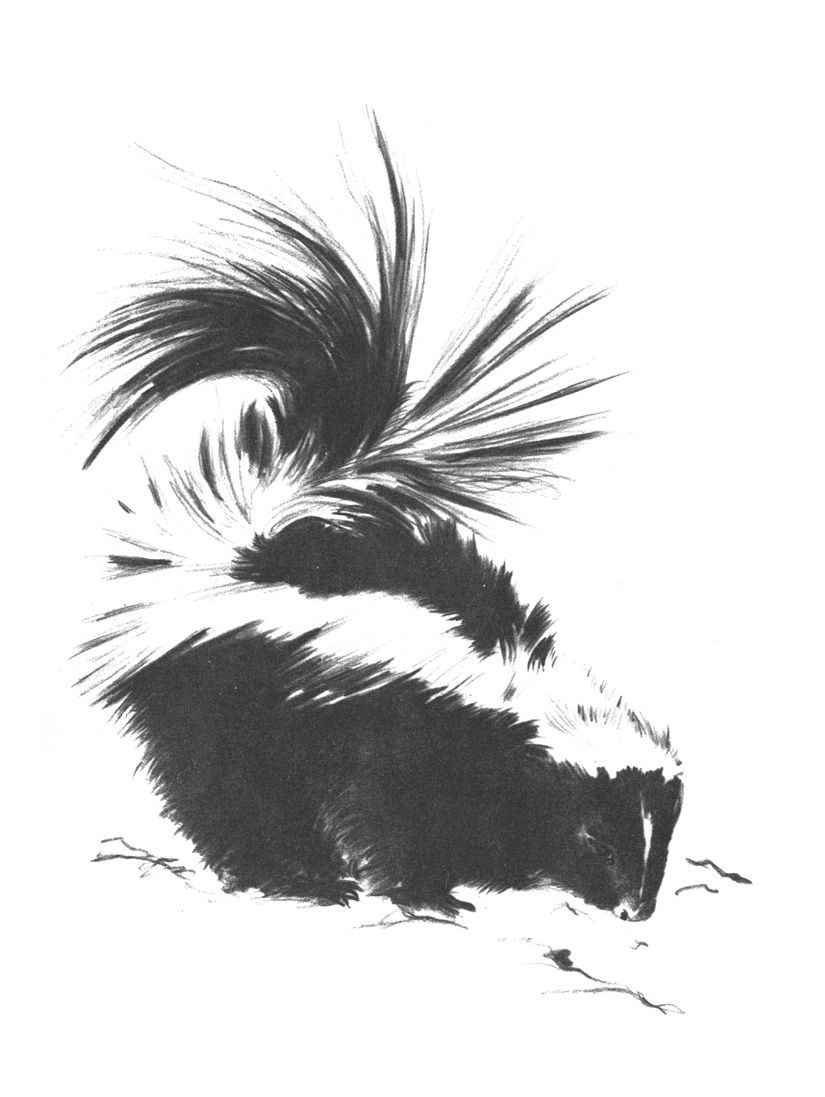

It was on the Iowa farm that he had his first interview with a skunk. As he told it afterward, the meadow larks were sweetly warbling, and all Nature was smiling and glad, when a big, bad skunk suddenly rose out of the landscape. He was a perfect whale of a skunk. He was heavily armed, and I was not. He carried a deadly revolver. He faced me. His beady, black eyes glared. He made a series of short runs at me,snarling, showing his teeth, and stamping on the ground with his black front feet, most defiantly. Few and short were the words we said.

As William imagined it, the skunk said: Run, you little skeezicks! Run, or it will be the worse for you.

You get off this prairie, the boy answered. You are too fresh.

I dare you to try to put me off, the skunk said. If you dast to try it, Ill make you bury your clothes for four weeks.

Realizing that the skunk meant business, the boy whistled three times. It was a signal. Williams older brother Calvin, working on another part of the farm, came running with his new shotgun in his hand. And that was the end of that skunk.

A sudden encounter with six big and beautiful white birds on the same bit of prairie provided a different experience, however. The sight of them shining in the sun was so thrilling to the boy that he could not sleep. His impression of those birds would stay with him always. And years later, at college, his vivid recollection would be matched by an illustration in a book, and he would be able to identify them as whooping cranes.

Williams father and brothers were all crack rifle shots, and Calvin undertook to teach the boy how to shoot. The first lesson involved a gray squirrel which, together, they spotted in the top branches of a large maple tree. William was given a Kentucky rifle, put in position, and told how to use it. Then Calvin crept around to the other side of the tree to distract the squirrel.