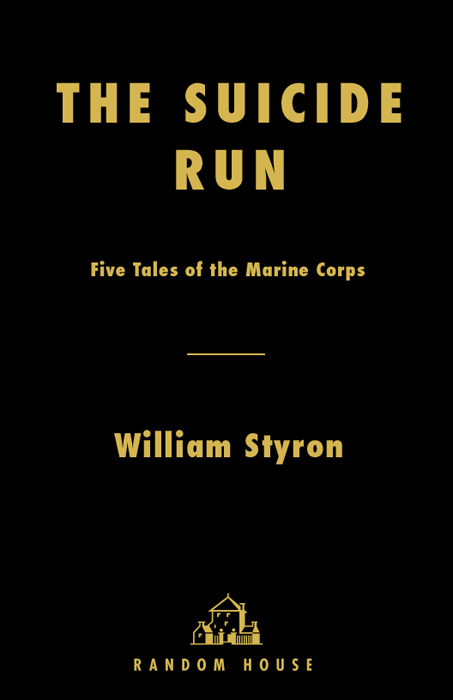

William Styron - The suicide run: five tales of the Marine Corps

Here you can read online William Styron - The suicide run: five tales of the Marine Corps full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2009, publisher: Random House, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The suicide run: five tales of the Marine Corps

- Author:

- Publisher:Random House

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The suicide run: five tales of the Marine Corps: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The suicide run: five tales of the Marine Corps" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The suicide run: five tales of the Marine Corps — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The suicide run: five tales of the Marine Corps" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

ALSO BY WILLIAM STYRON

Lie Down in Darkness

The Long March

Set This House on Fire

The Confessions of Nat Turner

Sophies Choice

This Quiet Dust

Darkness Visible

A Tidewater Morning

Havanas in Camelot

A MID THE SMELLY STRETCH of riptides and treacherous currents formed by the confluence of the upper East River and Long Island Sound stands a small low-lying island. Surmounted for most of its length by ancient prison buildings, it is an island hardly distinguishable, in its time-exhausted drabness, from those dozen or so other islands occupied by prisons and hospitals which give to the New York waterways such a bleak look of municipal necessity andfor some reason especially at twilightthat air of melancholy and erosion of the spirit. Yet something here compels a second glance. Something makes this island seem even excessively ugly, and a meaner and shabbier eyesore. Perhaps this is because of the islands situation; for a prison island it just seems to be in too nice a place. It commands a fine wide view of the blue Sound to the east and the white houses on the mainland nearbyhouses which, though situated in the Bronx, are so neat and scrubbed and summery-looking as to make New York City seem as remote as Nantucket. One passing by the island might more logically envision a pretty park here, or groves of trees, or a harbor for sailboats, than this squalid acre of prison buildings. Yet perhaps its the buildings themselves which make the place look more than ordinarily grim and depressingso that the cleanly utilitarian, white marble structures on the other of the citys islands seem, by comparison, almost beguiling sanctuaries. These date back nearly a century, soot-encrusted brick piles of turrets and fake moats and parapets and Victorian towers. With these, and with their crenellated battlements and lofty embrasures and all the sham artifices of fortressed power, the buildings possess a calculated, ridiculous ugliness, as if for someone locked within the walls they must add to the injury of simple confinement the diurnal insulting reminderin every nook and cranny unavoidable and symbolicof his incarceration.

Time has imparted little dignity to the place. Rain and soot and wind have weathered it, but the stain which they have printed upon those grandiose walls seems to have left no patina of mellowness, and has only made them more dirty. It would be a sad place to be. In any case, whichever makes the island so oppressivethe prospect, so close, of the clean white houses, or the prisons appalling architectureeither, to anyone held captive there, would make the idea of freedom more precious. Precious enough, indeed, that a man might riskgiven enough anguish, and enough furythe mile of channel, and the extraordinary tides.

It so happened that during most of the last war the island and prison were in the possession of the United States Navy, which had leased the place from the city in order to lock up members of its personnelsailors and marines and coast guardsmenwho had offended against the rules and regulations. These prisoners (although the population naturally fluctuated, it rarely went below two thousand men) were not major offenders. That is to say, they were not men who had murdered or committed treason or viciously assaulted an officer or committed any crime so dreadful that the total weight of naval wrath and justice had sunk mountainously about them and had swallowed them up for twenty years. But if these men had not been guilty of supreme crimes, they were not precisely minor offenders, either: they had thieved and raped and deserted and had been caught committing buggery and had been drunk or asleep, or both, while on duty and had been, almost to a man at one time or another, away without leave. They had all received courts-martial of some sort, and their average term of sentence was three and a half years. Yet, possessing neither the respectability of innocence nor the glamour of ruthless criminals, they shared a desperate, tribal feeling of inadequacy and were often victims, even within themselves, of sour contempt. No one displayed this contempt, however, with such cocky amusement as the marines who were on the island to guard them, and who called them simply yardbirds.

The prisoners were a sad lot, and the marines (there were two hundred of them, officers and men) ruled the island with a piratical swagger and a fine grip on the principles of intimidation. Few prisoners were ever beaten, for this in itself was a court-martial offense; but the history of bondage has shown that to slap a man about invites rebellion, while a tyranny of simple scorn cows the will and ulcerates the soul. Armed only with short billy clubs of hickory, the marines sauntered safe and serene and with a wisecracking arrogance among the fidgety horde, poking ribs and facetiously whacking behinds. The prisoners were gray with the grayness of men who seldom are exposed to light and suffer the sick, constant ache of loneliness. It was the peculiar grayness somehow stamped only upon the perpetually browbeatena lackluster and forlorn complexion, the hue of smoke. By day the prisoners workedmaking rope in the rope shop, shoveling coal in the power plant, hauling garbage, sweeping and swabbing their barracks floors. Then there was an enormous siren, mounted atop a water tower. It was this machine, like an intransigent apocalyptic voice, which seemed to dominate the island and the proceedings of each day. Like an archangels horn, too, it was apt to blow at any hour. It had the impact of a smack across the mouth, and at its shocking, pitiless wail the prisoners fled galloping across the island like panicked sheep, egged on by the ma rines rowdy cries. Shortly then, in front of their barracks (because always perhaps this morning one of them, in grief and desperation, had climbed down off the seawall), they were checked and counted one by one, standing in desolate ranks beneath the wide unbounded sky and the outrageous brick battlements and towers.

But if it was the enlisted marines who so mortified the prisoners, it was the officers on the island (there were twenty-five of them, seven marine officers in charge of the guard and the rest naval men: legal experts and administrative officers, doctors and dentists, chaplains to attend to the prisoners unmanned spirits, and a psychiatrist or two to adjust their often chaotic heads) who enjoyed sovereign and unchallengeable power, and to whom the prisoners accorded a cowering respect. At their approach the prisoners scrambled erect, removed their caps (being forbidden to salute), and stood in alarmed and rigid silence. Such were the rules, and thus even the meanest lieutenant might feel that same spinal thrill and hot flush of privilege that a cardinal must feel, or a general at parade, and sense chill little ecstasies of dominion. Yet of all these officersincluding the marine colonel in charge of the island, and the ranks of brass beneath himnone was treated by the prisoners with such craven and flustered diffidence as a certain marine warrant officer named Charles R. Blankenship. This in a way was remarkable, for he was not a cruel or angry man.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The suicide run: five tales of the Marine Corps»

Look at similar books to The suicide run: five tales of the Marine Corps. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The suicide run: five tales of the Marine Corps and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.